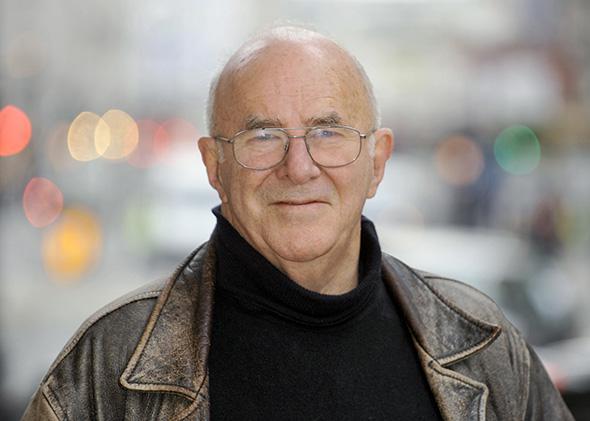

The terminally ill Australian polymath Clive James, 74, a longtime contributor to Slate, has written the kind of poem that will bring your day to a standstill. “Japanese Maple” appears in the Sept. 15 issue of The New Yorker and it is heartbreakingly lovely, a concentrated infusion of truths about nature’s amplitude and the human condition.

The rhyme scheme—ABABB—is a traditional English quintain, not unlike the second half of a sonnet with its closing couplet. The short third line in the middle represents the heart of each stanza, as well as the poignant trailing off of the A rhyme sound. Sonically, the stanzas are back-loaded, irrevocable in their drifting fall from A to B. There is a sense of heaviness and rest, and of beginnings ghosting away. Robert Browning’s poem “Porphyria’s Lover” uses the same template, without the pruned thought in the center; that lyric unfolds a story about strangulation, told serenely. (“No pain felt she,” says the unhinged narrator, “I am quite sure she felt no pain.”)

But I don’t want to dwell too much on form. What gives “Japanese Maple” so much of its throat-catching grace are its gentleness, resignation, and images that somehow achieve the emotional resonance of hard-earned wisdom. “Your death, near now, is of an easy sort,” James begins, conversationally, to himself. (He will move into the first person as the poem gathers resolution, commitment to its own difficult goals.) The speaker captures the fleeting discomfort of “breath growing short” (in a truncated line), but then the rhythm resumes as he notes that his “thought and sight remain” intact. He says he appreciates “fine rain” on a “small tree.” Yet he transforms this familiar tribute to “the little things” into something bigger—the scene outside the window broadens into gorgeous extravagance: “Ever more lavish as the dusk descends/ This glistening illuminates the air./ It never ends.” The poem, opening out as its speaker drains away (an irony captured in the brevity of the line “it never ends”), luxuriates for a moment in the permanence of the rain. Then it contracts to acknowledge that James can only “take my share” of the everlasting bounty. The rest will come “beyond my time.”

And that’s the headspace we are in when James introduces his daughter, who picked out the maple tree. She is both the promise of posterity and an aching reminder of what he will lose. That central ambivalence erupts, synaesthetically, in the next sentence’s incredible image of the tree: “Come autumn and its leaves will turn to flame.” The burning maple is loveliness and destruction intertwined, of course, and the vividness of experience, and the always-startling thereness of the seasons. But it also sets up the short fragment that follows, which feels both stunning and harsh in its simplicity: “What I must do.”

What the speaker must do is die. But the lyric defers that destination: James resolves instead to “live to see” the maple’s leaves turn red. In the final stanza, he conjures us into the future, with a vision of the burning tree “filling the double doors to bathe my eyes” so that “a final flood of colors will live on.” His anticipation of completion and fulfillment, so different from our sense of dread, is wrenching. Carefully the language—“fill,” “bathe my eyes,” “flood”—summons the possibility of tears while skirting their explicit mention. But the short third line packs another emotional punch: The apparition of the maple will overwhelm James’ sight “as my mind dies.” (In a way, he is talking about the sensory engulfment of death.) Now it is his consciousness consumed in fire, “burned by my vision of a world that shone/ So brightly at the last, and then was gone.”

Anyway, I’m crying at my desk now. Go read it.