Director Tate Taylor’s James Brown biopic Get on Up has already been praised as “Oscar-worthy,” “raw and unvarnished,” and “daring.” Many of these raves focus on Chadwick Boseman’s performance, which nails everything from the soul singer’s vocal mannerisms to his liquid dance moves. But is it faithful to Brown’s real-life story?

At 2 hours and 18 minutes, the movie necessarily glosses over entire decades of Brown’s life. It does stay true to much of his family background and early childhood influences, as well as many more minor historical footnotes such as his early, white-washed introduction of “I Got You (I Feel Good)” to the mainstream in Frankie Avalon’s Ski Party, as well as the times the young James Brown was paid to box other black boys while blindfolded, for the entertainment of a white audience. When Get on Up does stray from fact, it doesn’t so much fictionalize as oversimplify: Several crucial moments are presented more one-dimensionally than how they played out in real life.

To fact-check the movie’s most unbelievable scenes, I spoke with R.J. Smith, whose acclaimed 2012 biography, The One: The Life and Music of James Brown, is widely considered the most in-depth account of Brown’s life available. I also consulted Brown’s 1986 autobiography, James Brown: The Godfather of Soul, and The James Brown Reader: Fifty Years of Writing About the Godfather of Soul (2008), edited by Nelson George and Alan Leeds. We’ve separated the fact from the fiction below.

Childhood

D Stevens - © 2014 - Universal Pictures

Like the heroes of many a biopic, Brown came from hardscrabble beginnings. The film gets right the poverty and abuse that characterized his childhood, including his father Joe’s gambling addiction, harvesting of turpentine, and long stints away from home.

Some of the details surrounding his mother, however, are less clear-cut in real life than they are in the movie. Whereas the film offers a narrative of mostly willful abandonment, a family friend has said that Susie Brown (played by Viola Davis) left because Joe tried to kill her by pushing her out of a window. (In the movie, Joe does threaten her with a gun.) Although Brown didn’t remember seeing his mother for decades, city directories from Augusta, Georgia point to Susie having lived with her family for periods during Brown’s childhood. The scene in which Susie appears unannounced at Brown’s famous Live at the Apollo performance is likely fabricated for dramatic effect. In reality, Brown’s then-wife searched for Susie in Brooklyn and rekindled the relationship sometime in the mid-’60s.

Some time after Susie left the family behind, Joe did enlist in the Navy, as in the movie, although not until James was a bit older, and only for two years. In the meantime, Brown lived with a relative named Aunt Honey, played in the movie by Octavia Spencer.

As in the movie, Aunt Honey (real name Hansone Washington) ran a brothel where bootleg whiskey was readily available. The story Aunt Honey tells Brown about having been born dead is true—Brown was stillborn, but his Aunt Minnie breathed into his lungs until he could breathe on his own. This origin story was one Brown would return to time and again, as it gave him a feeling of invincibility in later years. Aunt Honey’s prophecy that Brown would one day become rich is also true, according to Smith’s biography. One night after a bath, she saw the hairs on his arms cross in a way that she took as a sign that he was “marked” for future prosperity. What the movie leaves out is how Aunt Honey abused Brown, told him he was ugly, and made him hide in the closet when johns came over. Her brother Melvin also beat Brown, once hanging him from the ceiling and whipping him with a belt.

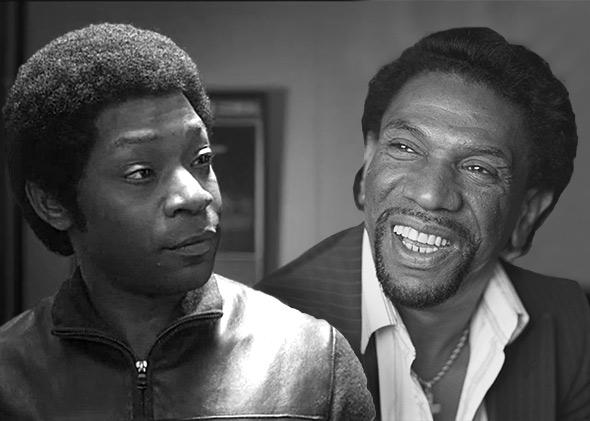

Bobby Byrd

Photo illustration by Slate. Screenshot via YouTube/Universal Pictures; Photo by David Corio/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

While the movie has Brown and Bobby Byrd (Nelsan Ellis) first meeting at the youth prison infirmary, the two didn’t actually meet on the day the Gospel Starlighters performed there. Brown had been sent to prison for stealing several items of clothing: a few suits, as well as a trench coat and some pants. (In Get On Up, he’s given several years in jail for stealing a single suit.) With no defense lawyer, he pleaded guilty and was sentenced to two-to-four years of hard labor for each count of theft. He was later transferred to a youth facility in Toccoa, Georgia, where the Byrd family lived.

After performing at the facility, Byrd became intrigued by rumors of a singer nicknamed “Music Box.” They met later, at a baseball game between prisoners and community members (it was a low-security, rehabilitation-oriented prison, with many opportunities to interact with the community). Brown did live with the Byrds upon his release, and he dated Bobby’s sister Sarah, although the movie omits Sarah’s membership in the Gospel Starlighters.

Brown and Byrd are depicted as having had a complicated friendship, but in real life their relationship was even more complex. The movie downplays the fact that Byrd had some success as a solo artist, and that Brown actually encouraged the careers of members of his road show. Once they became too successful, however, Brown felt threatened and took efforts to dampen their success by calling radio stations and demanding that they play his records instead of theirs. Brown’s relationship with Byrd seesawed frequently: Byrd would leave, Brown would beg him to come back, and Byrd usually would. Around the time of Brown’s death, however, Byrd (who died just nine months later) was still suing him for royalties.

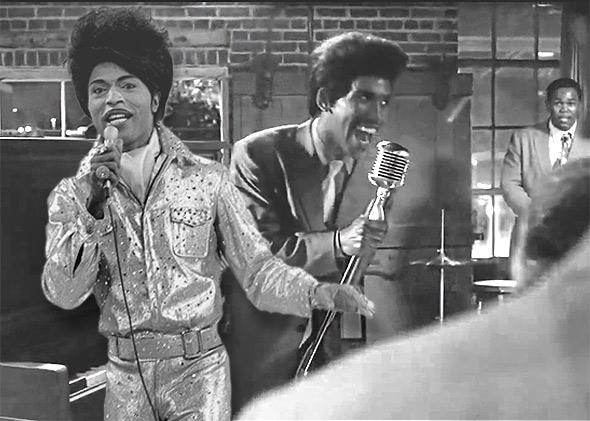

Gospel Starlighters and Famous Flames

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images; Screenshot via YouTube/Universal Pictures

Brown’s first meeting with Little Richard (whose flamboyance Brandon Smith plays with gusto) happened more or less as it plays out in the movie, although rather than taking the stage without permission, Brown asked Little Richard if his band could accompany him. Little Richard declined, but did allow them to play during a break, after which he suggested they contact his manager, Clint Brantley. Brantley agreed to manage the band, who were renamed the Famous Flames after their transition from gospel to R&B, and helped them record “Please, Please, Please” at a Macon, Georgia radio station. After hearing that record, Ralph Bass of Federal Records traveled to Macon to find and sign the band, as in the movie (though rather than meeting Brown and Byrd in a diner, he tracked down their manager in a barber shop).

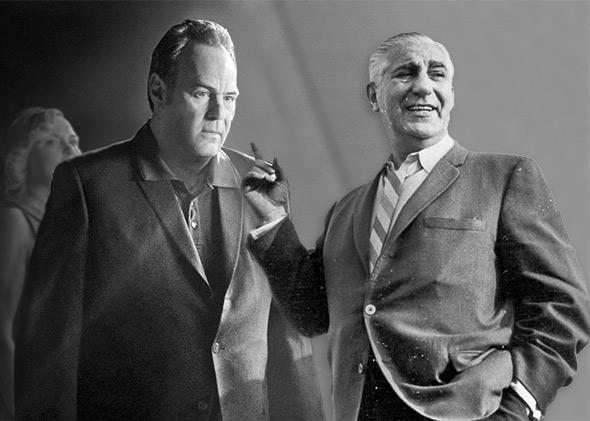

Making it Big

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by D Stevens/Universal Pictures; Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The meeting in which Universal Attractions agent Ben Bart tells the Famous Flames that it was going to be the James Brown show from that point on did happen, but the Flames didn’t quit on the spot. They all left the meeting feeling betrayed, and upon later seeing the record attributed to “James Brown with the Famous Flames,” several of them quit for good, others temporarily.

The movie’s depiction of Brown taking the reins of the business aspect of his career fails to give Bart the credit he’s due. While Brown did have a shrewd business vision, it was largely based on what he’d picked up from Bart. Bart had a legendary black book of DJs and club-owners in different towns and knew what to offer them to promote Brown. Though the film shows Brown feeling deeply emotional at Bart’s funeral, it downplays both the extent to which Brown saw Bart as a father figure, and the less than amicable terms their relationship ended on. By the time of Bart’s death, Brown had mostly cut him out of his career.

Activism

D Stevens - © 2014 - Universal Pictures

Some of the details surrounding Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and the concert Brown performed afterward are oversimplified. Chronologically speaking, the film has Brown find out about King’s death while recording “Mother Popcorn (You Got to Have a Mother For Me),” which wasn’t actually recorded until 1969. While Brown’s defusing of the tension at the April 5 concert in Boston was undoubtedly brave, and even a risk to his life, some ulterior motives were at play. Brown refused to go onstage until Mayor Kevin White agreed to pay him. He used the night’s tension to his advantage, though his actions were still deservedly considered heroic.

Brown’s trip to perform in Vietnam, seen at the beginning of the film, was also a political statement, not in favor of the war, but of appreciation for black soldiers who deserved to be entertained just as white soldiers were by Bob Hope. As the movie depicts, he brought with him a white bass player, Tim Drummond, whose inclusion in the band (Brown could only bring five members and had his choice from a much larger group) signified racial unity to the soldiers abroad. The scene in which Brown’s plane is struck by incoming fire with him and his bandmates on board appears to be embellished or invented. However, the visit certainly was a risk to the musicians’ lives—it took place during one of the most deadly periods of the war.

Later Years

As far-fetched as it seems, Brown did bring a shotgun to one of his office buildings, go off on a rant about people using his bathroom, and lead police across state lines in a fourteen-car chase. The movie elides many of his other troubles later in life: The IRS seized his house and sued him for $9 million; he had two more marriages both characterized by domestic violence and substance abuse; the police visited him at least 10 times over the course of two years; he struggled with drug abuse and went to rehab; and he was indicted for a number of felonies. As the movie’s post-script states, he did continue touring well into his seventies: Following his death at 73 on Christmas Day, 2006, Brown’s previously scheduled New Year’s Eve concert in New York City was converted into a memorial service.

Previously:

How Accurate is Jersey Boys?

How Accurate Is The Monuments Men?

How Accurate Is Lone Survivor?

How Accurate Is The Wolf of Wolf Street?

How Accurate Is Captain Phillips?

How Accurate Is American Hustle?

How Accurate Is 12 Years a Slave?