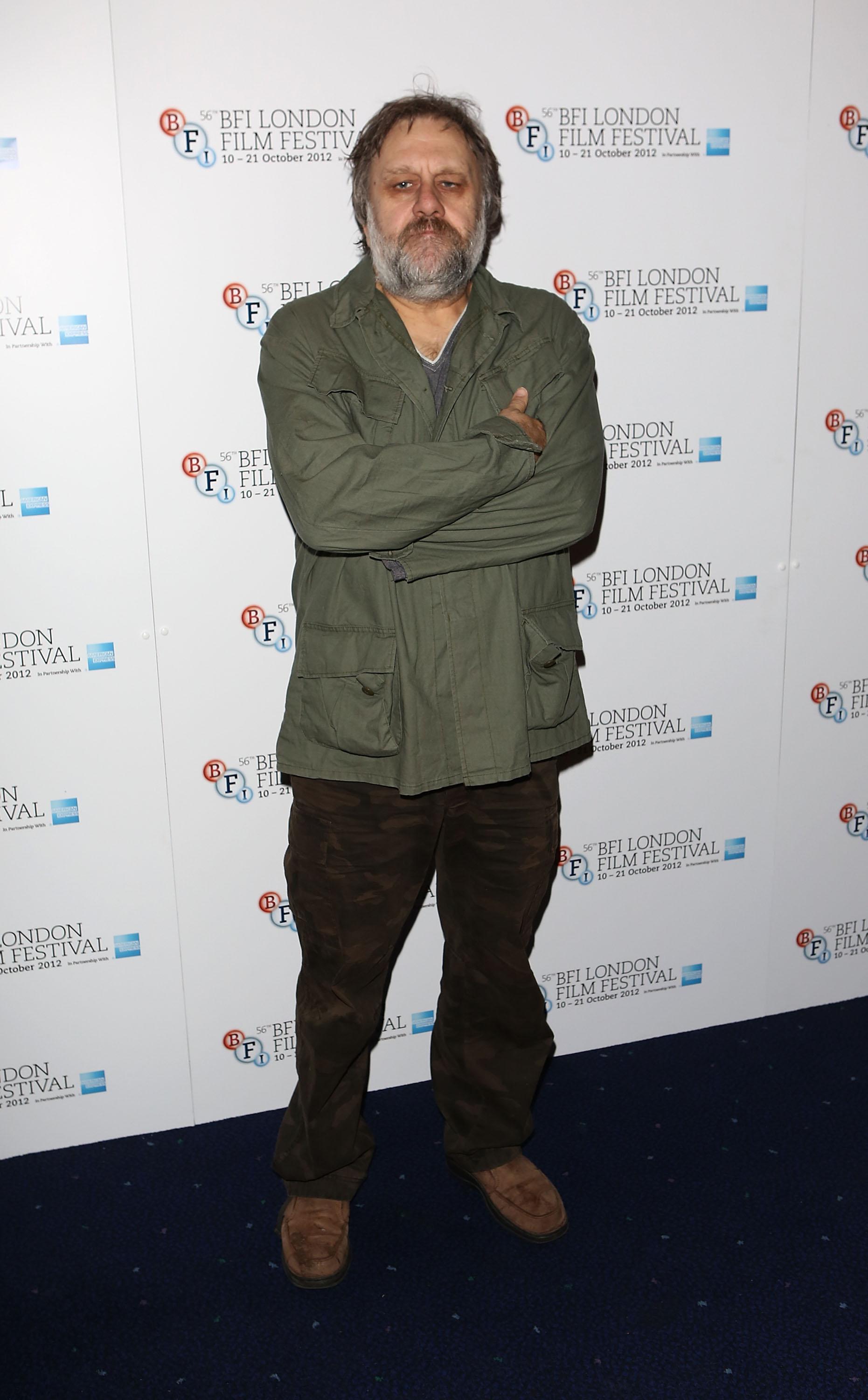

2014 has not been a banner year for superstar Marxist philosopher Slavoj Žižek. First, there was a viral video of him appearing to sneer with disdain at the very students whose rapt sycophantism makes his career possible. And now, he’s been accused of the worst professorial misdeed of them all: plagiarism. And not just any plagiarism—plagiarism of a 1999 article in American Renaissance, a white supremacist magazine published by an organization that the Southern Poverty Law Center has designated a “hate group.”

It all started when the conservative writer Steve Sailer and the mystery-shrouded blogger “Deogolwulf” both noticed something very odd about a few passages in a 2006 Žižek article in the prestigious academic journal Critical Inquiry. The prose in these passages, they realized, was far too lucid. “The reason for the cat’s barking, the dog’s meowing, or rather, this obscurant’s lucidity, is simple,” Deogolwulf explains. “It is someone else’s summary.”

Žižek typically writes in the tradition of Derrida, Foucault, and other icons of Critical Theory, who object to clear, identifiable theses on philosophical grounds (long story). Here’s an example of a classic Žižek passage (which is itself quite heavily indebted to Derrida):

Word is murder of a thing, not only in the elementary sense of implying its absence—by naming a thing, we treat it as absent, as dead, although it is still present—but above all in the sense of its radical dissection: the word ‘quarters’ the thing, it tears it out of the embedment in its concrete context, it treats its component parts as entities with an autonomous existence: we speak about color, form, shape, etc., as if they possessed self-sufficient being.

Reaching such passages in the context of the new plagiarism charges raises some obvious questions. Do Žižek’s editors read Žižek? Does Žižek even read Žižek? Does anyone actually read, all the way through, the articles of Slavoj Žižek other than the two self-professed conservative writers, Sailer and Deogolwulf, who apparently peruse six-year-old issues of Critical Inquiry for fun? (I emailed briefly with both of them, and both, while unfailingly professional and polite, declined to comment for this story).

Deogowulf’s damning side-by-side comparison of the Žižek article “A Plea for a Return to Différance (with a Minor Pro Domo Sua)” and Stanley Hornbeck’s 1999 piece has set off a bona fide kerfuffle. “We’re very sorry it happened,” James Williams, Critical Inquiry’s senior managing editor, told Newsweek. “If we had known Žižek was plagiarizing, we would have certainly asked him to remove the illegal passages.” (“Maybe he does this all the time,” snipped Hornbeck.)

As much as Žižek’s detractors want to believe that he has a similar (and inexplicable) affinity for back issues of American Renaissance as they do Critical Inquiry, there is actually a fairly understandable explanation for the whole thing—one that comes from Žižek himself. The philosopher explained, in an email to Eugene Wolters at the Critical Theory blog:

A friend told me about Kevin Macdonald’s theories, and I asked him to send me a brief resume. The friend send [sic] it to me, assuring me that I can use it freely since it merely resumes another’s line of thought. Consequently, I did just that – and I sincerely apologize for not knowing that my friend’s resume was largely borrowed from Stanley Hornbeck’s review of Macdonald’s book. […] As any reader can quickly establish, the problematic passages are purely informative, a report on another’s theory for which I have no affinity whatsoever […] In no way can I thus be accused of plagiarizing another’s line of thought, of »stealing ideas.« I nonetheless deeply regret the incident.

Like many eminent scholars, Žižek sought the help of someone else (who, for some reason, isn’t jumping to claim credit) to act as de facto research assistant. Research assistants complete the most boring and least glamorous parts of scholarship, like putting footnotes into Chicago Manual style, double-checking quotes, and, in some cases, providing quick summaries of books—in this case, Kevin MacDonald’s The Culture of Critique, part of a dubious series which is widely considered anti-Semitic. Unfortunately, the friend Žižek enlisted was big into providing summaries (someone else’s summaries!) and not so big into double-checking quotes (and neither, apparently, were Žižek or his editor at Critical Inquiry).

Although Žižek’s defense—that lifting Hornbeck’s “purely informative” summary does not count as real plagiarism—is not correct, I understand his predicament. Famous academics have their minions do their dirty work all the time. And most of these minions are legitimate scholars who would not steal someone else’s words (especially not someone who writes for a white supremacist rag). So when one of them says, “Sure, you can use this verbatim,” Žižek has no reason not to do just that.

However, in the wake of this scandal, everyone might want to be a little more careful. Maybe when your research assistant or “friend” sends you a chunk of text and carte blanche to use it, cut-and-past a few phrases into Google—as we do with student papers that set off our plagiarism detectors (usually because they, too, suddenly boast passages that are far too lucid for their authors). Because who knows? The next “helpful” passage a superstar scholar accidentally passes off as his own could be this: “Reading is not an end in itself, but a means to an end.” (Oh, that? That’s from Mein Kampf.)