How simple can a song be? How wrong can a song be? Is this real?

I woke up this morning to the news that Tommy Ramone, the original drummer and last surviving member of the Ramones, had passed away. While it is not surprising that Tommy—the “normal” Ramone—outlived the other three original members, his passing does close a remarkable chapter in music and pop culture.

The Ramones’ first album was a fearless presentation of fantasy and reality. It was the “you gotta hear this” album of 1976. In a recent documentary, longtime Ramones collaborator—and possibly the band’s biggest fan—Daniel Ray candidly admitted he and his friends would laugh when they put the first album on. So did I, and so did many of the kids who loved the Ramones. It was a mind-blowing, impossible set of songs. It was as ridiculous as it was scary. This was Punk Rock version 1.0, the foundation upon which all other punk rock music would be based.

I must admit that I never really understood the definition of the word punk until a few years back. I never understood why in old movies grown men would jump up and punch someone in the face after being called a punk. Wasn’t it like being called a little jerk? Evidently the truth behind the word, at least from the grizzled NYC know-it-alls I hang with, is that it was street slang for a younger gay lover or rent boy, so to call someone a punk was beyond calling someone a fag. It was calling someone a whore and a fag. To embrace punk as the title of their musical movement is so in keeping with the Ramones’ stance. Just the sheer fucked-up-ed-ness of the first album’s first two songs, “Blitzkrieg Bop” and “Beat on the Brat” (“with a baseball bat”). Were they even worried about being misunderstood? Who cares? Get lost. This song isn’t for you or your mother either.

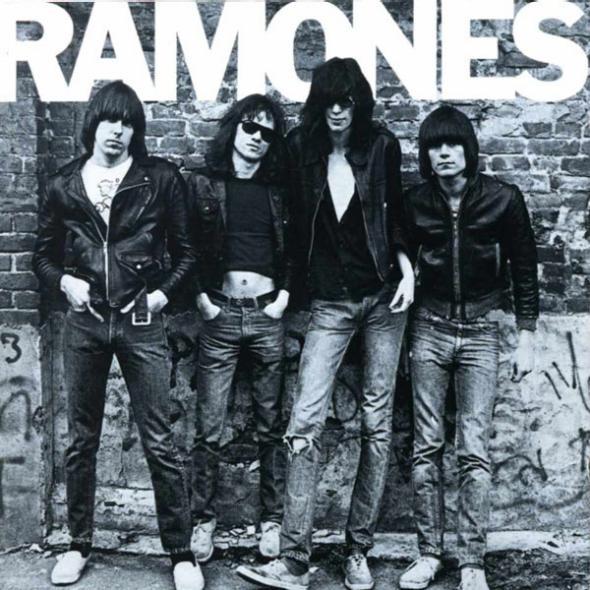

Which brings us to the impossible unity of the Ramones. They all had the same last name. They all wore the same outfit and haircut. All the songs started with “1 2 3 4.” The monolithic, unified roar. And, most importantly, all the songs seem to come from a musical universe that they were the sole inhabitants of. Although their eagle logo and leather-clad image invited dopey imitation in the way all of rock music’s orthodox rebellion does, the Ramones’ original iconography not only illustrated they were tough, but that they were one. For an earlier music generation, the Beatles’ idea of the band as a gang, jumping over hilltops together, was part of their initial appeal. The Ramones were a gang as a band. A few years before his passing, Dee Dee Ramone complained about when he was starting with the band being forced to get a “Ramone” haircut. Having that small part of their image dismantled that way broke down more of the image of the band for me than I anticipated.

It is preposterous to call the Ramones performance art, but is there a more intentional, self-contained creative performance? The Ramones weren’t a band “about something.” While there were other high-concept bands that rival their singularity of statement—like Kraftwerk, the Residents, or Devo—those bands revolved around technology and enigma. The Ramones were self-reflexive: a rock band that was about the idea of a rock band. They took comic book violence and the deadest tropes of Beach Boys lyrics and placed them alongside tales of New York hustling as if it all was one piece. Authenticity wasn’t an issue. Authenticity was a joke.

The influence of the Ramones is certainly musical—as much about reintroducing the charm of a short song as the power of a barre chord—but it goes far beyond music. A Ramones song cannot be unheard. The Ramones changed the pH balance of rock music’s pond water. Their existence challenged everyone else’s. They’re not part of a school. They built the building.

Right after Tommy’s death was announced, someone posted “The Ramones are getting back together” on social media. Was the writer being mean or sentimental or just stark? How fitting an epitaph for Tommy, Dee Dee, Joey, and Johnny, and to that I say: 1 2 3 4.