The first time I can recall hearing Casey Kasem count down the hits on American Top 40 was on a Sunday in June 1981. Just shy of 10 and in the car with my cousins driving to the beach, I asked them to stop flipping the radio when they landed on Kasem, who was just a couple of songs away from revealing that week’s No. 1 hit. I’d glimpsed Kasem once or twice before that, on America’s Top 10, the television version of his countdown show, which ran on Saturdays after cartoons ended. But hearing Casey on the radio that Sunday, doing the full Top 40 show, was what hooked me.

The prior week, Casey explained, Kim Carnes’s summer smash “Bette Davis Eyes” had been ejected from the top spot after five weeks on top; it had been overtaken by a bizarre dance medley of old pop songs that went by the name “Stars on 45.” But, Kasem teased, “Bette” wasn’t out of the picture yet; maybe it could come back. I knew who I was rooting for. I made my cousins stay on the station—they poked fun at me the whole time for being wrapped up in this drama—until Kasem revealed that Carnes’s hit had indeed returned to No. 1. (“Bette Davis Eyes” wound up on top four more weeks, nine in all, solidifying its status as the top song of 1981.)

Obviously my rooting interest in the outcome was based in my tween love for the Carnes song, plus my enjoyment of anything involving numbers. But the drama—that was all Casey. “We’re just a coupla hits away from the number one song in the USA,” he’d promise, in that twinkly, seemingly always delighted voice of his. The tease was the man’s art form: With a couple of well-placed pauses, he could build suspense for the next record on the countdown, whether it was rising to No. 1 or spending its eighth week there.

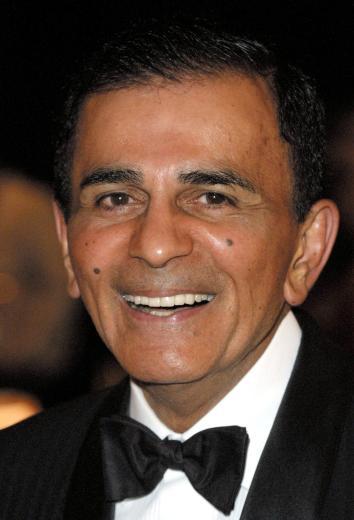

This explains why so many pop fans are feeling the loss of the man born Kemal Amin Kasem in Detroit in 1932. Casey died Sunday at age 82 after a protracted illness and a sad battle among family members over his care, now blessedly over. For fans of the Billboard charts and hit music, the Top 40 is our sport, and Casey Kasem was our Howard Cosell and Bob Costas rolled into one. Like Cosell intoning about the thrill of victory or the agony of defeat, Kasem could even make a pithy epigram for how the charts work sound momentous: “Radio plays ’em, record stores sell ’em, Billboard ranks ’em, and AT40 counts ’em down.” Like Costas, he seemed eternally unflappable, his voice rock-steady and unmistakable (even when he was lending it to a cartoon stoner).

While that voice has been accurately described as courtly, folksy, comforting and warm, Kasem was also immensely skilled at making every chart move sound like a story. Even halfway through a countdown, mid-tier hits warranted bits of recounted dialogue that made Boy George sound like a next-door neighbor stopping by to borrow a cup of sugar. And waiting for the end of the four-hour show was always worth it: With timpani thundering in the background, Kasem would announce that week’s top record according to Billboard, often preceded by a story that could make Madonna sound like Esther Blodgett—finally capturing the ear of America after a career of hard-knock striving.

Kasem was the play-by-play man of the monoculture, with a preternatural understanding of the power of pop to unify. And like an earnest pop fan, he took his passion seriously. No one did countdowns as well as he did because no one respected them, or worked at them, or treated them as a craft as much as he did.

The idea of counting down hit records wasn’t novel in the late ’60s, when Casey and his hometown friend and radio producing partner Don Bustany (like Kasem, a Lebanese-American from Detroit) began pitching the idea of a national countdown show. Your Hit Parade, on radio starting in 1935 and TV in the ’50s, had already come and gone, and radio stations across the country maintained local Top Five or Top 10 countdowns through the early rock ’n’ roll years. But Kasem had been dreaming of a coast-to-coast countdown show for the better part of a decade, less as a music fan than as a broadcaster who knew a countdown could serve as a framework for a series of artist biographies, trivia, and radio-friendly stories. When American Top 40 premiered during July 4th weekend 1970 on just seven U.S. stations, it already benefited from Kasem’s years behind the mic. In the first half-minute Casey sounded like he’d been doing the show for years, segueing smoothly between introducing the No. 40–ranked Marvin Gaye song and teasing a story about the gold hubcaps on the car of the artist at No. 39.

Eight years later—with AT40 now a staple on hundreds of stations nationwide as well as Armed Forces Radio—Kasem’s instincts led directly to what became the show’s most celebrated feature, the Long Distance Dedication. As AT40 expert Rob Durkee chronicles in his book American Top 40: The Countdown of the Century, Kasem kept the idea on a back burner for most of the show’s first decade until the perfect letter appeared: a lovelorn kid pining after a girl named Desiree and requesting the Neil Diamond song of the same name. From then on, the LDD was a staple of Kasem’s broadcasts, right up until he retired three decades later. Again, it was a trite idea made new—the old radio shout-out on steroids, powered by carefully curated listener mail and a national megaphone. Again, the secret weapon was Casey, who could make even the most mawkish sentiments powerfully relatable. A letter from an Arkansas college student who’d just come back from a year abroad pining for a sweet British guy—a story that somehow ends with her request for the Beatles’ “Drive My Car”—finally puts a catch in your throat the moment Casey pauses before saying, “OK, Mary Kay, here’s your Long Distance Dedication.”

Even Kasem’s bloopers were exhibits to the premise of caring too much. The infamous “dead dog tape,” a long-circulated mid-’80s outtake reel of Kasem cursing a blue streak, began when his script editors tried to place an LDD about a pet dying after an uptempo, tonally inappropriate Pointer Sisters hit. (This rather contradicts the Kasem obituaries attesting to his uninterest in the songs he counted down; their sound did matter to him.) His other great foul-mouthed outtake, about U2—“These guys are from England, and who gives a shit,” quoted gleefully by music critics to this day and immortalized on a sued-out-of-print EP by the musical art project Negativland—grew out of Kasem worrying to his producers that he didn’t know enough about the band and was having a hard time discussing their hits. Call the guy sentimental or old school, but he wasn’t phoning it in.

For the average American who enjoyed some segment of the hit parade, Kasem was a folksy tour guide to the music soundtracking their lives. But for those among us who would grow up to become music critics or chart geeks, Casey was something more—our earnest, omnivorous nerd leader. Casey Kasem was the original poptimist, believing that a full range of popular music can be as important and worthy of appreciation as rock. He championed centrist pop even when it was unfashionable to do so.

Which was basically from the beginning: AT40 premiered in 1970 just as radio was moving away from the pop-hit-driven AM model; but by decade’s end, hundreds of FM stations, which wouldn’t otherwise touch half or more of the dance-y hits peppering the Top 40, ran Casey’s countdown. In the late ’80s, he survived and even thrived amid a downswing in Top 40 station ratings, ditching his original radio network—which wouldn’t pay him enough to count down the hits out of a belief that pop radio was dying—moving to a competing network, and dominating his old show in ratings and station count. He and Bustany eventually reacquired the rights to the American Top 40 title in the ’90s, and Casey counted down hits under that name from 1998 until 2004, before retiring in 2007.

Kasem’s career lasted long enough to see his devotion to centrist pop return to the heart of American culture, surviving our dalliances with rockism and irony. Kasem put the broad in broadcasting, building a big tent under which pop was for everybody. His career is a testament to the idea that music is not about dividing but uniting—from coast to coast.