Footprints. A ripple in a glass of water. A rustling in the trees. Perhaps a shadow or a glimpse of a tail before—finally—the close-up. The big reveal makes or breaks a monster movie. Either the audience is primed to feel awe and terror in that moment, or you’ve made a monster mistake.

The narrative going around about the new Godzilla, which waits about an hour before it finally gets to the fireworks factory, is that it’s a radical return to this kind of old-fashioned creature-feature restraint. 21st century Hollywood movies are glutted with CGI, the story goes. Today’s audiences are “more accustomed to orgiastic spectacle than foreplay,” says Vulture’s article on Godzilla’s “bold approach,” headlined “What Everyone Who Sees Godzilla Will Be Talking About.” David Edelstein’s review for the site agrees, contrasting director Gareth Edwards with “most modern sci-fi directors, who throw so much CGI at you that they make miracles cheap.” In the Atlantic’s review, cleverly headlined “Waiting for Godzilla,” Christopher Orr writes that Edwards’ approach is a throwback to the original: “Edwards introduces the monster gradually—a glimpse here, a glimpse there—as Toshiro Honda did with the original Godzilla 60 years ago.”

This narrative seems compelling—kids these days with their short-attention spans and sophisticated computer modeling!—but none of it is quite right. If anything, modern monster movies, and not just Godzilla, are waiting longer than ever.

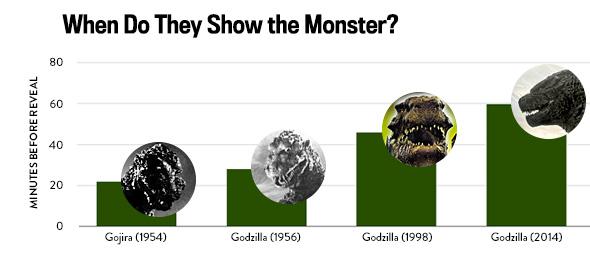

For starters, reports of the original Godzilla’s restraint have been greatly exaggerated. 1954’s Gojira waited only 22 minutes before showing his giant lizard face. Since then, each of the successive Godzilla reboots and remakes has waited longer than the one before.

Illustration by Holly Allen

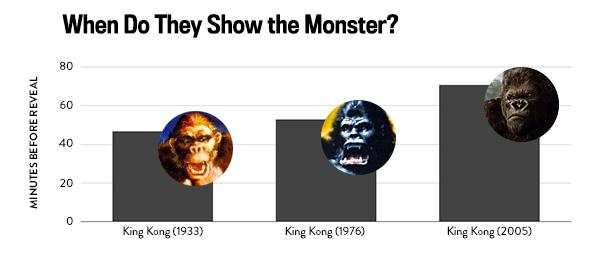

Godzilla’s elder bash brother, King Kong, has held to a similar trend. The original King Kong waited an agonizing 47 minutes before bursting through the trees, but the two reboots since have waited even longer. (Too long, according to many reviewers of Peter Jackson’s 2005 King Kong.)

Illustration by Holly Allen

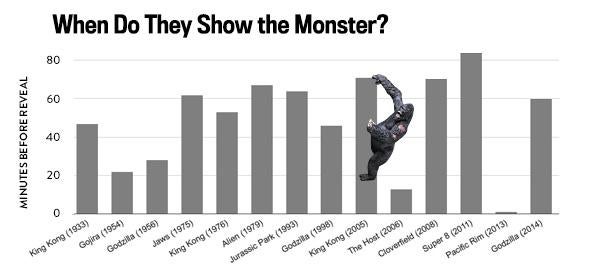

It’s not just those two franchises. Vulture correctly points to 1975’s Jaws (which waits 62 minutes before the shark pokes up its head) and 1979’s Alien (which waits 67 minutes before flashing the full xenomorph) as models for the slow reveal. Jaws’ mechanical shark Bruce was famously dysfunctional, and the crew’s difficulties with the machine prompted director Steven Spielberg to delay the reveal even longer than he originally planned. But when Spielberg got a major technological upgrade before Jurassic Park (1993), he still waited 64 minutes before showing the T. rex. (For the velociraptors, he waited even longer.)

Illustration by Holly Allen

Other movies had prolonged the tease long before Bruce’s breakdown. Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People (1942), about a woman who believes she transforms into a panther when aroused to passion, was famous for harnessing the power of suggestion: It never showed the transformation. And there have always been producers who demanded to see all their money on screen: When Tourneur went on to make Night of the Demon (1957), producer Hal E. Chester insisted that they show the monster in their first scene.

“As a simple dramatic principle of writing something scary, the unknown is the most frightening thing,” Alien screenwriter Dan O’Bannon has said. “Make the audience squint, stare and try to catch glimpses of the thing in the shadows. Underexposure is always more effective than overexposure when you’re trying to scare people.” Alfred Hitchcock put this a different way: “There is no terror in a bang,” he famously said, “only in the anticipation of it.” The movie that kicked off the whole trend, King Kong (1933), conveyed this as well as any since: The native villagers of Skull Island have built a whole ceremony around the monster’s semi-regular appearances, and as they wait for the stop-motion ape to appear, they dance, chant, and writhe in an ecstatic crescendo—signaling to us in the audience how we should react. (Guillermo Del Toro has called this the “pageantry” of monster movies, noting, “So many horror films are almost like shrines to their creatures.” Gareth Edwards has used a different metaphor, calling it “cinematic foreplay.”)

Occasionally a movie will successfully zig where others have zagged. The great South Korean monster movie The Host (2006) makes a point of underplaying its reveal. (The joke in that surprisingly funny monster film is that the monster’s prey don’t understand that they should be afraid—instead they try to feed the monster.) And Pacific Rim (2013) followed a template closer to the Godzilla vs. films, finding pleasure instead in steadily revealing more and bigger monsters. (“In Mexican horror films, we show the monster—a lot,” Del Toro has said. “My theory is that it’s because it costs so much.”)

Every so often critics announce that hiding the monster is coming back—especially when there’s a new movie out from J.J. Abrams, who has made a signature out of this sort of striptease, with Cloverfield (2008) and Super 8 (2011). But the truth is it’s never really left. Movie history has long shown that it’s a good idea to wait about an hour before trotting out your creature for his big close-up. Still, there’s no hard-and-fast rule, and certainly no guarantee that waiting any amount of time will fix an otherwise terrible movie. Just ask Godzilla (1998).