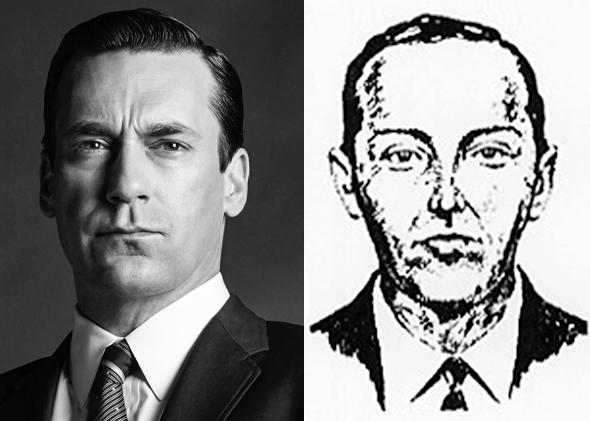

One of the most outlandish and compelling theories about the final season of Mad Men was succinctly outlined on Medium last year: Don Draper, our magnetic and perpetually dissatisfied hero, will turn out to be the legendary skyjacker known as D.B. or Dan Cooper. Cooper was the alias of the man who, in 1971, hijacked a Boeing 727, secured parachutes and $200,000 dollars, jumped out of the plane somewhere between Seattle and Reno, and was never heard from again.

The idea that Don might turn out to be Cooper makes a certain amount of sense. The name Don Draper sounds like Dan Cooper. Mad Men has long been fixated on air travel—even this year’s promotional teaser features Draper descending from what looks like a 727, though one parked on the ground, and via a staircase. More poetically, Draper is forever trying to escape the confines of his own life, and Cooper fanatics believe he pulled off the greatest such escape in American history. (The FBI, on the other hand, believes he died.) And of course there’s Mad Men’s opening credits sequence, which features Don falling, falling, falling.

Are the Internet sleuths behind this theory onto something? To find out, Slate interviewed Geoffrey Gray, whose 2012 book Skyjack chronicled Cooper’s disappearance and the legions still obsessed with finding out who he was and where he is now. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Slate: You have not watched a minute of Mad Men. Do you think the theory sounds plausible?

Gray: My first instinct was “no way.” The Mad Men vibe just doesn’t jibe with who Dan Cooper was on that plane. Mad Men—it seems like they try to capture this glamorized version of the ’50s and ’60s advertising culture. Like a three martini lunch, a three gulp martini drinker. And Cooper was not that. He was a little bit of a schlub.

Slate: The Mad Men vibe is about suavity, it is about glamour. But as the show has gone on, people are starting to look a little less suave and wear a little more polyester. Let me run you through a couple of different classic characteristics of Don Draper, and you can tell me whether you think they might apply to Dan Cooper. Did the hijacker look like Jon Hamm as Don Draper?

Gray: Well the first problem is that he’s got the wrong color eyes. The second problem is that Cooper had marcelled or curly hair. Other than that, there’s some things alike. In every official Cooper sketch Cooper had hair parted to the side [like Draper’s]. He’s got the wide forehead. His age is right. His age is very right. One can imagine a situation where you look at that wanted poster of D.B. Cooper and see this man Draper. I don’t think it’s a stretch.

There’s also the skinny tie. That was one of the things about Cooper’s tie. The FBI looked at the model and wanted to know what year it was from, and it was actually from the ’60s.

Slate: So he was still wearing a skinny tie even as the ties got wider? That’s very Don.

Gray: Yeah. Apparently the tie was sold at J.C. Penney. It was a Towncraft tie from ’67 or ’68. Clip-on.

Slate: There’s no way Don Draper would ever wear a clip-on tie. On the other hand he is someone who’s hanging onto the ethos of the ’60s as the years progress on the show.

Gray: One of the things that I learned from the FBI files that I was able to get my hands on for the reporting of the book is that Cooper wasn’t this debonair guy at all. That’s the myth. But the actual dude on the plane was hardly debonair. One witness described the color of his suit as “russet,” like this burgundy suit, with this off-color shirt. And this clip-on tie. And to me, Don Draper would have had to be totally on skid row to go into a Goodwill store and get this outfit and hijack the plane.

Slate: Next major characteristic of Don Draper: He is very adept with women, is one way to put it. Cripplingly obsessed with them, is another. What do we know about Cooper’s relationships with women?

Gray: Well some speculate that there were flirtations going on between him and the stewardesses on the flight. I don’t really think that that’s true. One of the things, universally, that psychologists found with hijackers in the early ‘70s was that they all struggled with women. Dan Cooper was not, by any means, a happy guy. One stewardess said to him, according to the FBI files, “Do you have a grudge against Northwest Airlines?” And he said “No, miss. I just have a grudge.” I get the sense that the guy was a loner. He was very much accustomed to being by himself and not in the company of others, female or male.

Slate: Don Draper is also a lonesome character, even though he’s socially adept. He’s not emotionally intimate with anybody. And part of that is because the character of Don Draper is an assumed one. He was born Dick Whitman, and then during the Korean War, assumes Don Draper’s identity as a way of separating himself from a painful childhood. Any analogues there?

Gray: Absolutely. Not only was Dan Cooper likely an alias, but many people suspected at the time were people living under assumed names. The ’50s and ’60s were a time when some people were desperate to leave their lives. They felt trapped in their marriages or their jobs, and they were seeking freedom. And one of the ways to do that, because technology wasn’t advanced as it is today, was just to take over somebody’s name. You could forge licenses easily. One of the clues that I chased was that Dan Cooper, whoever he was, found an old magazine story called “How to Leave Your Life.” And followed the directions on how to leave your life, and just went to the beach one day with his wife and kids, and said he needed to go to the bathroom, and went to the restroom at the beach and never came home. It was a wild and wooly time back then, and it was much more permeable to be who you wanted to be and change who you are. So that definitely fits. It’s also worth noting that the name Dan Cooper is the name of a French comic book character who flies airplanes in the Royal Canadian Air Force and jumps out of them. But I’m not sure if Don Draper is a comic book enthusiast or has any relationship with French Canada.

Slate: Don’s wife is French Canadian.

Gray: Well there you go.

Slate: So Dan Cooper was a French Canadian comic character?

Gray: Yeah, and the comic book artist lived in Montreal for a time. This comic book came out all throughout the ’60s about Dan Cooper.

Slate: Do you believe that the hijacker was a veteran?

Gray: Absolutely. Cooper had to make a choice on the plane that tells us a lot about who he was. He was given two parachutes: One was a Pioneer canopy chute, and one was an NB6—a Navy Back 6—and he could only choose one. The Pioneer was a civilian chute, the Navy Back was a military chute. Often used in the Korean War, by the way, in the Navy. So if Cooper was a civilian and had civilian jumping experience, he would have naturally gone with the Pioneer, experts believe. If he had military experience he would have gone with the military parachute, which was far older, much harder to steer. Cooper chose the Navy Back 6. And the majority of people believe, including me, that the reason Cooper did it was because he knew that rig. He had military experience, and he picked the pack that he was comfortable with. And that was one that he could have very much learned in Korea.

Slate: Well, Don Draper was in Korea, but in the Army, not the Navy. In terms of parachute training, for someone to make that jump…

Gray: It is possible for a novice or an early jumper to have made the jump. And the only reason I know that is that at the time, the FBI wondered the same thing. How experienced a jumper does this have to be? And they interviewed experts who told them that at 10,000 feet, which is relatively low altitude, 6 or 7 jumps would be enough to figure out how to do it. To do the free fall until the appropriate altitude. So it’s quite possible that an ad exec could have pulled this off with a couple of weeks of training.

Slate: Why do you think so many people were fascinated with Cooper’s story?

Gray: He represented something very potent in that moment. He became a sort of counter-culture hero, a bad guy who even the good guys wanted to get away. He was a sort of sky pirate, a bizarro Robin Hood. He was able to, as an individual, overtake these big complex things called airplanes, this big complex thing called law enforcement, and make away with a fortune at a time when the country was in a recession and a cultural civil war. The problem from a factual point of view, though, is that Cooper was made into this cultural hero. And the truth is that the guy who hijacked the plane and the guy who everyone thinks hijacked the plane are two totally different people, in my opinion.

Slate: What are the key distinctions between the myth and what the reporting suggests is true?

Gray: There’s an obsession, within our culture, with the genteel thief. Somebody who commits a crime, but does it in a classy way. And Cooper jumped into our national imagination through the trope of the genteel thief. But there’s nothing in the case files that suggests he was genteel at all. Quite the opposite: Yeah, he smoked cigarettes, but he smoked the shittiest kind. He was a guy with a grudge, not a guy with a mission. And he was troubled, as many of the hijackers were. Hijacking airplanes, you’re risking suicide. You’re risking murder. These are tremendous things that have nothing to do with heroism.

Slate: That notion of a man who does bad deeds in a classy way is very much in keeping with Don Draper. He’s someone who keeps winning us over. It sounds like the fictional character of Don Draper might be aligned a bit better with the romantic myths surrounding D.B. Cooper than the actual reality as far as we can know it.

Gray: One of the side characters in the Cooper thing said “We all have a little larceny in our hearts.” We’re attracted to bad guys, and we like to follow bad guys, because they do things that we want to do but just don’t do, for whatever reasons. My feeling is people would rather Cooper not be found than be found. They’re rooting for him to constantly, constantly get away, because the longer he gets away the more we can engage with the romance of getting away with it ourselves.

Slate: Did you feel at the end of writing the book that you’d figured out who he was?

Gray: I found him so many times I quite nearly lost my mind. At some point I was convinced that four different people were Dan Cooper, and I believed that all were. But I was more interested in what the character meant, not only to those who spent their lives and their fortunes using submarines and all kinds of wild stuff to find this guy, but also what he meant for the moment when he jumped.

Slate: And what was that?

Gray: He represented a sort of momentary gasp of freedom. And not only breaking free from the constraints of society—whether it’s a moral code, or the efficiency of the corporation, or the law enforcement chasing him, or his own demons—he also represented freedom from gravity. He’s a very compelling criminal to root for.

Slate: Well, we’ll have to wait and see whether Don jumps.

Gray: How come somebody doesn’t just go invade the writing room? Isn’t this a job for an investigative reporter to parachute in and figure out what’s going to happen? It’s not that tough.

Slate: I think that would spoil some of the pleasure of letting it all unspool.

Gray: Somebody should just get the script!

Slate: This can be your next book, Geoff.

Read all of Slate’s coverage of Mad Men.