Earlier this month, the New York Times ran a profile of the writer Walter Kirn; despite the somewhat ridiculous portrait it paints of its subject—tetchy, narcissistic, bluntly preoccupied with his own expensive underwear—he emerges reasonably well from the piece, and with the reader more, rather than less, likely to read his new book Blood Will Out. The reason for this is that Kirn is not just the subject of the profile, but also its author. The article mocked the genre of the newspaper profile as much as it did the writer himself, benefiting in particular from the specific in-built comedy of the paper’s insistence on prefixing surnames with titles. (“‘A writer who isn’t writing,’ Mr. Kirn reflects, tossing a pair of dark socks into his bag free-throw style, ‘is asking for trouble.’ ”)

Reading it, I realized that I’d seen various versions of this stunt over the years, and that it seems to be particularly popular with writers, many of whom exhibit a generally playful attitude toward literary forms. Moreover, many writers combine a tendency toward self-regard with a skepticism about that tendency. Kirn’s self-interview immediately reminded me of a piece John Banville wrote for Newsweek in 2007 in which he “interviewed” Benjamin Black, the quasi-pseudonymous persona under which he publishes crime fiction. Kirn’s is probably less thematically justified, but it’s more successful, or at least more amusing; Banville seems so pleased with himself for coming up with the idea in the first place that he winds up forgetting to do anything with it.

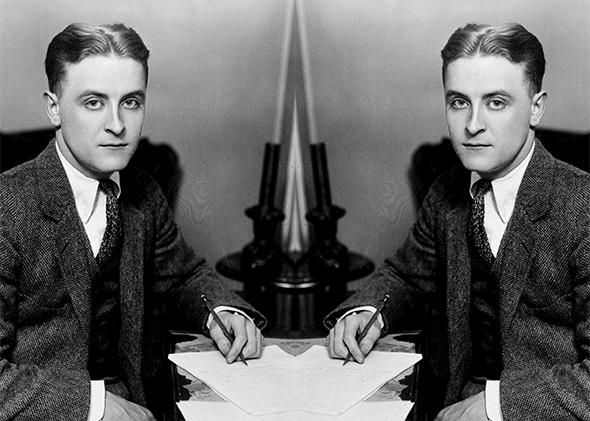

The stunt feels sort of quintessentially postmodern, and of a piece with the tendency of writers to turn themselves into characters in their own work (something which has featured prominently in books by the likes of Kurt Vonnegut, Martin Amis, J.M. Coetzee, Roberto Bolaño, and Sheila Heti; in the films of Charlie Kaufman, and in sitcoms like It’s Garry Shandling’s Show, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and Louie). But the self-interview form has been around for a surprisingly long time. In 1893, George Bernard Shaw sat down for a chat with his own ego, which resulted in the prankish Shavian curiosity “The Playwright on His First Play.” (He asks himself whether Shakespeare has served as a model for his own work, and then jumps down his own throat: “Shakespeare! Stuff! Shakespeare—a disillusioned idealist! A pessimist! A rationalist! A capitalist! If the fellow had not been a great poet, his rubbish would have been forgotten long ago.”) As a publicity stunt for This Side of Paradise when it came out in 1920, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote a short profile of himself called “An Interview with F. Scott Fitzgerald.” The piece, one of the more enjoyable entries into the self-interview canon, begins:

With the distinct intention of taking Mr. Fitzgerald by surprise I ascended to the twenty-first floor of the Biltmore and knocked in the best waiter-manner at the door. On entering, my first impression was one of confusion – a sort of rummage sale confusion. A young man was standing in the centre of the room turning an absent glance first at one side of the room and then at the other.

“I’m looking for my hat,” he said dazedly. “How do you do. Come on in and sit down on the bed.”

The author of This Side Of Paradise is sturdy, broad shouldered and just above medium height. He has blond hair with the suggestion of a wave and alert green eyes—the melange somewhat Nordic—and good-looking too, which was disconcerting as I had somehow expected a thin nose and spectacles.

Tennessee Williams followed suit with a Q and A called “The World I Live In”, published in The Observer in 1957. (Q: “Can we talk frankly?” A: “There’s no other way we can talk.”) A decade later, Norman Mailer tried his hand at it in the New York Times Book Reviews. It would have been a weird omission from the self-interview canon had he not.

It has never really been a popular enough move to become a cliché, but it has been employed by a remarkably broad constituency of creative public figures: Walker Percy, Joyce Carol Oates, Bun B, Ingmar Bergman, Nicki Minaj, Bob Balaban, Nick Nolte, and Sam Lipsyte (on the website The Nervous Breakdown, which runs an ongoing series of self-interviews).

The most fascinating example of the form, though, is also probably the most objectionable: Vincent Gallo’s downright unhinged self-profile for Grand Royal, the magazine the Beastie Boys published in the mid-1990s. The actor/director/artist/breakdancer/supermodel/singer-songwriter gives his own wide-ranging and comprehensive self-obsession full reign here. And as always with Gallo, there’s the sense of a performatively ironic douchebaggery masking an even more extreme non-performatively ironic douchebaggery.

We got there at exactly the same time. I watched him walking in and it was like they say, you know, he kind of glowed. Like a ray of light was around him. A kind of Jesus. He was wearing a light pink leather suit that had airbrushed flames all over, and engraved into the leather were flowers, hearts and bunnies. He made it himself. God, he does it all. He also made his patent leather hat which was frayed into the shape of Warren Beatty’s hair in the movie Shampoo. And a pair of transparent Adidas that Mr. Adidas made for him in 1981. He was wearing solid gold socks underneath.

The self-conscious absurdity of the piece doesn’t lessen the impact of its quintessentially Gallovian combination of grandiosity, misogyny, and racial antagonism. The whole thing is so grotesquely overdetermined, though, that it seems to transcend and subvert the limitations of the self-interview form. It reads like the horribly comic manifestation of a deep and obsessive narcissism, as opposed to the writerly manipulation of these qualities. It works, in other words, almost as a sort of accidental deconstruction of the self-interview’s inherent smugness, which is why anyone considering attempting that form would be well advised to read it.