I’m a competent cook but not a fastidious one. It rarely seems worthwhile to invest time and effort in geometric refinement: by dicing a potato into exact cubes, for instance, or by using a small ice cream scoop to make my lumps of cookie dough perfectly even. When I’m in the mood for impressive aesthetics, I go to a nice restaurant—or to a Wes Anderson movie.

Anderson’s latest, The Grand Budapest Hotel, is more gastronomically inclined than most of his films: Part of the frame story takes place over an elaborate meal at the titular hotel, and pastries play an important role in the main plot. One pastry in particular is shown over and over again: the courtesan au chocolat from the fictional Mendl’s Bakery, a stack of three chocolate-filled profiteroles frosted in pastel hues.

The courtesan is not a pastry that exists outside of the imaginary country, Zubrowka, in which The Grand Budapest Hotel takes place—a promotional website for the film calls the courtesan au chocolat “the true and popular symbol and herald of a small mountainous nation.” The real-life pastry the courtesan most closely resembles is a less colorful two-tiered French confection called the religieuse. A religieuse is typically filled with vanilla custard and glazed with chocolate or mocha ganache, and its name means nun, which it ostensibly resembles. (I don’t see it, personally.)

Sonia Geffrier via Wikimedia Commons

Calling his Easter egg-hued variation a courtesan seems like a deliberate repudiation of the chaste, saintly connotations of the convent. The hero of Grand Budapest Hotel is something of a courtesan himself, accepting gifts and money in exchange for sex and company—though his clients are women.

Then there’s the more obvious symbolism of the courtesans: They have three layers, just like the narrative of The Grand Budapest Hotel. And they are beautiful, colorful, playful, and needlessly elaborate—descriptors that apply to every film Wes Anderson has ever made.

But enough semiotics—how do the courtesans au chocolat taste? Last week, Anderson’s team released an instructional short video breaking down how to bake, fill, glaze, decorate, and assemble the pastries (which were developed by German baker Anemone Müller-Grossmann).

As (one of) Slate’s resident re-creators of cinematic foods, I resolved to give them a try, a task that would require abandoning my usual laissez-faire attitude in the kitchen and adopting an Andersonian attention to detail. After purchasing my ingredients, I put on the Grand Budapest Hotel soundtrack, heavy on the baroque influences, to get me in the mood.

I’d made pâte à choux—the eggy dough that makes éclairs, gougères, and other airy pastries—before. I’d also made custard before. So steps one and two—the pastry and the filling—were a breeze. Granted, I took a considerable shortcut: Instead of piping the pastry dough onto the baking sheets using a pastry bag, as Anderson and his team recommend, I spooned the dough onto the baking sheets like cookie dough. But I took extra special care to make them evenly sized, so I felt Anderson would approve.

I started running into trouble when I tried to get the chocolate custard inside the choux pastries. I’d misplaced my pastry bag—which I never use anyway—and so was left trying to pipe the chocolate pudding into each cream puff using a Ziploc bag with a decorating tip fitted perilously in one corner. I found myself stabbing larger and larger holes into each cream puff to try to facilitate the entry of the chocolate, which got all over the place despite my efforts. The whole thing made me feel rather queasy, as though I were an inept surgeon trying to rescue a disemboweling victim.

Like the plot of The Grand Budapest Hotel, the process of making the courtesans au chocolat got more complicated as the night wore on. Once filled, the pastries needed to be dipped in a simple glaze of powdered sugar, milk, vanilla, and food coloring. My first try at the glaze was too thin—it slid down the sides of the pastries like mascara-tinted tears down a cheek—so I made a new batch, determined to make my choux balls look like Anderson’s.

That determination evaporated during the next step: “Decorate the balls with filigree of white chocolate as desired.”

As previously established, I had no pastry bag, and attempting a “filigree” with a Ziploc bag seemed like madness. So I flung the melted white chocolate onto the pastries with a fork to create a Jackson Pollock-like effect. Then, for the final assembly, I succumbed fully to my natural negligence, dabbing blue buttercream between each ball haphazardly with a small spoon.

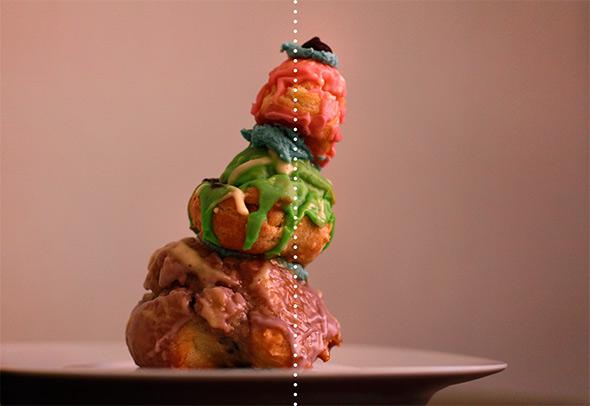

All in all, making the courtesans took about four hours. My pastries looked less like nuns or courtesans and more like deformed, lopsided snowmen. Their slapdash appearance was a far cry from the studied imperfections of their cinematic counterparts—many of them had an asymmetry that would never be tolerated in an Anderson film:

Still, my heart swelled with pride at the sight of them. Many critics have interpreted The Grand Budapest Hotel as a defense of Anderson’s aesthetic scrupulousness—a declaration that taking joy in paying attention to details can make life worth living. I will never make anything half as pristine as a Wes Anderson movie, but I can confirm that trying to make something beautiful (even if you go about it as clumsily as I did) feels pretty good.

L.V. Anderson for Slate

Read the rest of Slate’s very comprehensive Wes Anderson coverage.