The ending of Denis Villeneuve’s new movie Enemy has been called perhaps “the scariest ending of any film ever made.” And much of its scariness derives from its initial inexplicability. The movie has described as “head-scratching,” “mysterious,” and “gloriously enigmatic.” As one critic put it, “I kinda dug it but I have no idea if it’s any good or what happened or where I am anymore and what aiiiiiiiieeeeeeee that last sound/shot.”

This was my first reaction as well, but one thing critics haven’t done thus far—probably because they’re confined to the spoiler-free zone of the review—is offer a theory that tries to make sense of it all. This is a movie that begins with the epigraph, “Chaos is order yet undeciphered” (a line from José Saramago’s The Double, the novel on which the movie is based). Though the movie may appear inexplicable at first, this epigraph suggests that we can make some sense of it, some order, if we just know how it can be deciphered. And Villeneuve has backed this up. In an interview with the Huffington Post, he said, “If you look at Enemy again, you can see that everything has an answer and a meaning.”

Major spoilers ahead, obviously.

I’ll offer a theory. While Enemy has been billed as an erotic thriller and a doppelganger movie—and it is both those things—I think ultimately it’s a parable about what it’s like to live under a totalitarian state without knowing it. It’s an Invasion of the Body Snatchers movie in which you don’t even realize it’s an Invasion of the Body Snatchers movie until the end—until it’s too late for our hero. In this case, the body snatchers just happen to be giant spiders.

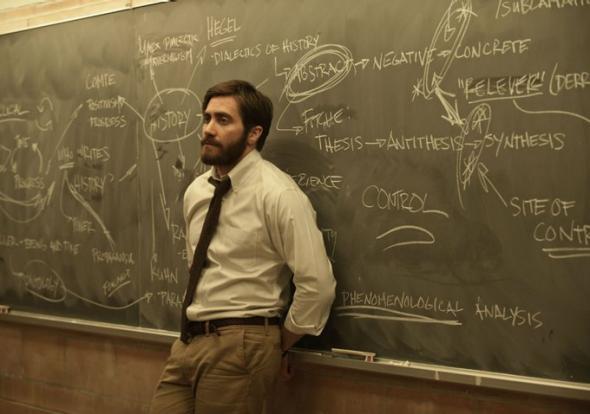

When we meet our hero, Adam Bell, he is lecturing about the ways that totalitarian states keep the people down. The Romans used entertainment, he reminds us, “bread and circuses.” This recalls the opening scene of the movie, which takes place at a sex show. There we see our first spider. Anthony, Adam’s twin, goes to these shows (we can distinguish the two because Anthony wears a wedding ring), and we later learn from his doorman that men will do anything to see them. Anthony’s profession also allies him with the entertainment industry—he’s an actor.

Adam, on the other hand, doesn’t much like entertainment. He, a professor, represents education, which, as his lectures remind us, totalitarian governments try to keep down. “You don’t go to the movies, do you?” his coworker asks him, out of nowhere, and he answers, “I don’t really like movies.” Indeed, as we’ve seen in a series of recurring shots, his interests don’t seem to involve anything more than lecturing about totalitarian regimes, drinking wine, and having sex with his girlfriend.

But the coworker is leading him somewhere. Adam figures he must have asked because he must be thinking of a specific movie. “You brought it up, and I thought maybe you had a recommendation.” The movie the coworker recommends ultimately leads Adam to discover what’s actually going on around him.

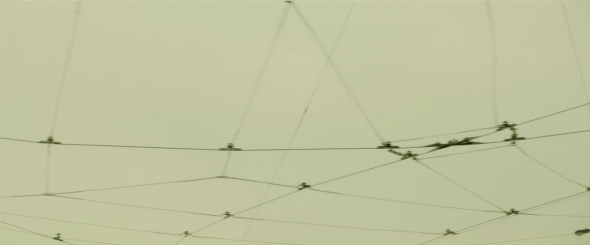

There are subtle clues about what’s going on in the city from the very beginning. We see low-angle shots lingering on the streetcar wires that make them look like spider webs:

Photo still © 2014 A24.

Bell passes a graffitied image of a businessman giving a fascist Roman salute:

Photo still © 2014 A24.

Anthony gets into a fight in the car with Adam’s girlfriend Mary (Mélanie Laurent)—“You don’t think I’m a man?” he says—which leads to a terrible crash, and the camera slowly zooms in on a crack in the windshield that resembles a spider web:

Photo still © 2014 A24.

Less subtle, of course, is the shot of the giant spider hovering over the city. A version of this shot also appears on the poster, where, perhaps notably, the spider is superimposed over an image of Anthony. (We can tell it’s him from the leather jacket, something Adam never wears.) Between his appearance at the spiders-and-sex show at the beginning, Mary’s accusations that he’s not a man, and the spider web Villeneuve shows us on his car window—not to mention that his wife turns out to be either a giant spider or perhaps a woman pregnant with one—Anthony clearly isn’t what he seems.

The central irony in all this is that even the main character, though he is an expert on the ways of totalitarian governments, doesn’t see the web that’s overtaken the city until he’s already stuck in it. As he says in the lecture, totalitarian states succeed because “they censor any means of individual expression” (my emphasis). When he finds out he has a double, that’s of course exactly what happens: He can never again be an individual.

While it’s surprising that Villeneuve and screenwriter Javier Gullón decided to turn an adaptation of The Double into a spider-infested parable about totalitarianism—at least according to my interpretation—it’s not completely random. Though the novel The Double doesn’t have any of this spider conspiracy, these themes were important to Saramago. When Saramago was 3 years old, a military coup overthrew the Portuguese government, and for the next 48 years, he lived under a fascist regime. His work frequently explores totalitarianism and his experiences under a fascist regime through metaphor and allegory. In 2007, he told the New York Times:

We live in a dark age, when freedoms are diminishing, when there is no space for criticism, when totalitarianism—the totalitarianism of multinational corporations, of the marketplace—no longer even needs an ideology, and religious intolerance is on the rise. Orwell’s ‘1984’ is already here.

Why spiders, specifically? It’s hard to say. There aren’t any eight-legged creatures in The Double. But there is this passage from Saramago’s The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, in which he weaves an elaborate metaphor comparing the fascist police and their allies to spiders:

There is no lack of spiders’ webs in the world, from some you escape, in others you die. The fugitive will find shelter in a boardinghouse under an assumed name, thinking he is safe, he has no idea that his spider will be the daughter of the landlady … a dedicated nationalist who will regenerate his heart and mind.

And where did the spiders come from? Why do fascist regimes arise again and again throughout history, in “a pattern,” as Adam reminds us? Enemy suggests that this tendency to create totalitarian regimes is part of human nature, that it comes from within us. After all, even Adam, the ostensible good twin, is an extremely flawed character—he sells out his girlfriend, cheats on her with another woman, and earlier he tries to rape her. As the movie goes on, he becomes more and more like Anthony. Villeneuve, who has otherwise been tight-lipped about his film, has said this about Enemy: “Sometimes you have compulsions that you can’t control coming from the subconscious … they are the dictator inside ourselves.”