This post contains spoilers about The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Wes Anderson is often criticized for pulling from the same monogrammed Louis Vuitton bag of tricks: He creates fastidiously arranged dollhouse worlds populated by the same ensemble of actors who deliver droll dialog in films suffused with nostalgia. For Anderson’s detractors, an aesthetic that felt so richly original in Rushmore—Anderson’s second feature, but the first to feel truly Andersonian—has in the ensuing years come to seem like a schtick, and a limitation. These critics want Anderson to engage with new themes on a bigger stage, but like Richie Tenenbaum, the director remains stubbornly zipped away in his childhood tent, pining for the past.

Those who have tired of Anderson’s approach will likely find little to love about The Grand Budapest Hotel, which is set in Anderson’s most magnificent dollhouse yet—the titular hotel—and is arguably his most nostalgic film to date as well. It’s misty-eyed not merely for lost boyhood, as has often been the case in his work, but for an entire Old World way of life, an era of handmade macaron towers, restorative mineral baths, and highly personalized concierge service. It’s easy to dismiss the film as an elegantly calligraphed love letter to more civilized times.

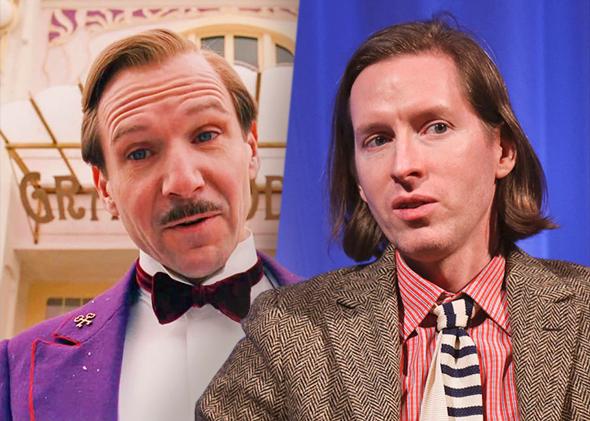

It’s undoubtedly that, but it’s also more than that—it’s a self-portrait of sorts, a glimpse of the man in corduroy behind the camera. M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes), the concierge of the Grand Budapest and the film’s flawed hero, is clearly a figure for the director himself. Both men create luxurious worlds, attend to them with an obsessive attention to detail, and coax excellence out of a large, occasionally unruly cast of characters. Consider this scene, from the film’s opening, in which we witness M. Gustave at work, attending to his guests’ needs while barking orders to his staff, holding them to the comically high standards he has set for his hotel.

Now compare that scene to another clip, from an ad Anderson made a while back for American Express:

Anderson is clearly offering a bit of self-satire in the ad, but the joke works because we’ve intuited the reality: He is anything but the absent-minded, capricious figure we see here, shrugging at new bits of dialog and tossing off absurd prop requests. We know in our bones that he’s much more like M. Gustave, seeing to it that every aspect of his carefully crafted vision is executed just so: straighten that hat!

We know this, in part, from Rushmore, which offered a portrait of the director as a younger man. Who but the precocious Max Fisher could have grown up to make the movie we’re watching? Here, Max directs the crew of “Heaven and Hell,” his theatrical pastiche of Vietnam movies, confidently stalking the halls of Grover Cleveland High like Gustave does the lobby of the Grand Budapest, as Anderson captures him in the same retreating dolly shot:

Though it’s set in a far-off land in the distant past, Grand Budapest Hotel feels like a companion piece to Rushmore. Both movies center on an intergenerational friendship—in Rushmore between Max and the enervated industrialist Herman Blume, here between M. Gustave and the energetic lobby boy Zero. A decade and a half later, however, it’s the elder of the pair who stands in for the director.

Skeptics might point to this as further evidence that the director hasn’t had a new idea since 1998, but there’s a crucial difference in the way Grand Budapest treats its Anderson figure. Near the end of the movie, an aged Zero reveals to the character we know only as “the Author” (who will go on to set down Zero’s story) that M. Gustave was a man out of time even in his own era. It’s a rather shocking revelation: We learn, at the very end of the film, that the opulent world M. Gustave had created at the Grand Budapest was a fiction, an attempt to recapture some old, faded notion of grandeur. M. Gustave was guilty, in other words, of precisely the crime we like to pin on Anderson.

It’s a blink-and-you-miss-it moment, but it’s a crucial one. It suggests that Anderson is very much aware of his own penchant for nostalgia—and that this film is an attempt to wrestle with its pull on his imagination. Learning that M. Gustave was straining to fight off the realities of a changing world lends his comic character a tinge of tragedy. He’s walled himself off in his well-appointed dollhouse, where he literally makes love to the past, cavorting with the bejeweled widows who frequent the hotel. That Anderson named one of them Madame D—a nod to Max Ophuls, one of his Old World idols—suggests he is very much in on the joke: Gustave’s weakness is also his own.

Zero, too, is caught in the past; while he recognizes M. Gustave’s penchant for nostalgia, he is nevertheless powerless to avoid a similar trap, passing his old age sitting in the tarnished splendor of the hotel, telling his story to the occasional guest. He’s like the ancient mariner, only with more refined manners, a well-stocked wine cellar, and a jaunty turtleneck.

Though our heroes are stuck in the past, they’re hardly alone. Word of their adventures is passed down from generation to generation, to a new listener or reader fascinated by a lost world. Gustave’s tale is first recounted by the aged Zero, then relayed by the Author, and finally read by a young girl in what looks to be the present day, seated beside a bust of the now-deceased Author. The past doesn’t just exert a pull on Anderson’s imagination, the film’s nested structure seems to suggest—we’re all susceptible.

Anderson may indeed be more susceptible than most. As Ralph Fiennes put it to the New York Times, the director “feels there’s a world that happened before, which he might have been happy in.” Fiennes added: “But there’s a bittersweet feeling from the nostalgia for the thing you never actually experienced, the time you never actually lived in.” The Grand Budapest Hotel is steeped in that bittersweetness, but it’s not just a nostalgic film. It’s a film about the perils of nostalgia—and the timeless allure, for all of us, of a better era just beyond our reach.