I live in New York, but I decided to spend a couple of weeks in L.A. this winter in order to escape the cold and snow. When I realized my trip would overlap with the Oscars, I started looking into getting a press pass to the ceremony. (My rationale: Why not?)

I was too late and too irrelevant to get a pass to the ceremony itself—those are reserved for legit entertainment reporters, not belligerent food bloggers. But I did manage to register for an “Oscars setup credential,” a badge that would give me “access to specific exterior locations [of the Dolby Theater] from 9 a.m. Monday, Feb 24, until 11 a.m. Sunday, Mar 2 (the day of the show).” Why anyone would want to stand around outside the Dolby Theater in the week leading up to the Oscars ceremony—but not during the ceremony itself—I wasn’t quite sure. But I assumed it would become clear when I actually got my press pass.

Instead, things got way more complicated. On Monday, I showed up at a conference room in a hotel behind the Dolby Center, got my picture taken, and waited around for my plastic badge to be printed out. In the meantime, I was asked to sign a contract that started out by saying that the badge “carries significant responsibilities.” (Remember, this is a badge that grants me access neither to the Oscars ceremony, nor to the inside of the Dolby Theater, nor to any Hollywood VIPs.)

The contract continued, “Do not post or share a picture of your credential on Facebook, Twitter, or any other social or online media. Images of credentials may not be published in any medium.” Finally, I had to agree to the following statement:

I understand and agree that credentials may not be copied or photographed and I agree not to copy or photograph the Credential or allow others to copy or photograph the Credential. Any unauthorized use or copying of the Credential … may result in civil and/or criminal prosecution.

My mind was boggled. (Though I guess it shouldn’t have been: There were signs plastered all over the conference room warning me against taking a picture of my badge, or of anyone wearing a badge.) Could the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences really prohibit me from taking a picture of a piece of plastic bearing my own name and face? Especially considering that the piece of plastic wasn’t even a pass to the Academy Awards ceremony?

Legally speaking, yes. Technically, the badge is the property of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences—they’re just lending it to me. And since it’s their property, they get to set the terms of use, so long as those terms aren’t discriminatory or unconstitutional. (Selfies, alas, are not constitutionally protected per se.) When I spoke to Jody S. Kraus, a contracts expert at Columbia Law School, he compared it to a restriction on photography inside someone’s home. “I can say, look, I’ll let you inside my house if you don’t photograph,” said Kraus. “If you want to get into my house, you’re going to have to give up some of your rights, and the same thing is true to some extent with the Oscars.”

So what would happen if I were to take a picture of the badge and post it on Facebook? The Academy would be able to sue me for breach of contract, if they so chose. According to Krause, if they could prove that I caused them some financial harm by photographing my badge, they’d be entitled to monetary damages. If they couldn’t prove any financial harm, they could ask for an “equitable remedy” in the form of a court order forcing me to destroy or turn over my badge and any pictures of it. They could also seek legal action against me for other reasons: For instance, if I violated the contract by photographing my badge, I would no longer have the right to those “specific exterior locations,” so I could be sued for trespassing if I tried to get in post-photo. And if someone somehow committed a crime as a result of my illicit Facebook post, I could be liable for criminal negligence or fraud. (As far as I can tell, no one’s actually gotten sued by the Academy for posting pictures of their pass—although the only Oscar pass pictures from previous years I could find online were published after the awards ceremony.)

Why is the Academy so afraid of reporters taking pictures of their badges? When I went to the Academy’s press office to inquire, staffers told me to send an interview request via email, to which I received no response. (I’ll update this post if I hear back.) But it’s easy to guess where the no-photograph rule came from: In 2008, professional gatecrasher Scott Weiss plotted to get into the Oscars and succeeded. According to BuzzFeed,

A week before the 2008 Oscars, Weiss and company staked out the Kodak theatre. “We would take photos with people with badges, ‘Hey! Can we get a picture with you?’ BAM! We would get as high-definition a photo as possible. Eventually, we were able to get enough photos that we were able to recreate in Photoshop a really good copy of the badge.”

Oscars organizers later enlisted Weiss and his accomplices to help improve security at the venue (which was renamed the Dolby Theater after Kodak went bankrupt in 2012). I’d bet heavily that the photography clause entered journalists’ contracts around this time.

The year after Weiss crashed the Oscars, an Academy spokesman told a reporter, “There is a distinct possibility that the publicity about these crashers, as well as the video itself, could serve as an inspiration or a road map for those looking to commit far more serious criminal acts.” But so far, Oscars crashers have tended to be people like Weiss, whose devious aim was to take pictures with a bunch of celebrities, and people eager for their 15 minutes of fame, like the 1963 crasher Stan Berman, the man who dubbed himself “Surfer Dude” in 2002, and the 1997 crasher who went on to write a book called How I Went to the Oscars Without a Ticket.

In other words, the people who tend to try to crash the Oscars aren’t political terrorists looking to assassinate heads of state. Threatening journalists with lawsuits if they tweet a picture of themselves wearing their badge seems rather disproportionate to the potential consequences of that TwitPic. It seems to me that the Academy ought to invest its resources in creating a badge that’s difficult to counterfeit, not in menacing badge-holders with legal action if they pose for a snapshot.

In spite of my skepticism, I’m not going to publish a picture of my press pass here. I signed the contract to get my badge, after all, and I’d prefer not to get sued. I’ll happily describe the badge to you, though: It’s a rectangular piece of plastic in tasteful blue and gray tones with “the Oscars” printed on it, along with the expiration date of the badge. (Which, remember, is hours before the Oscars begin.) There’s a headshot of me on it in which I’m smiling in the strained-looking way I always do when someone takes my picture. On the back of the badge, there’s a reminder that “Photographing or other copying of badges is prohibited.”

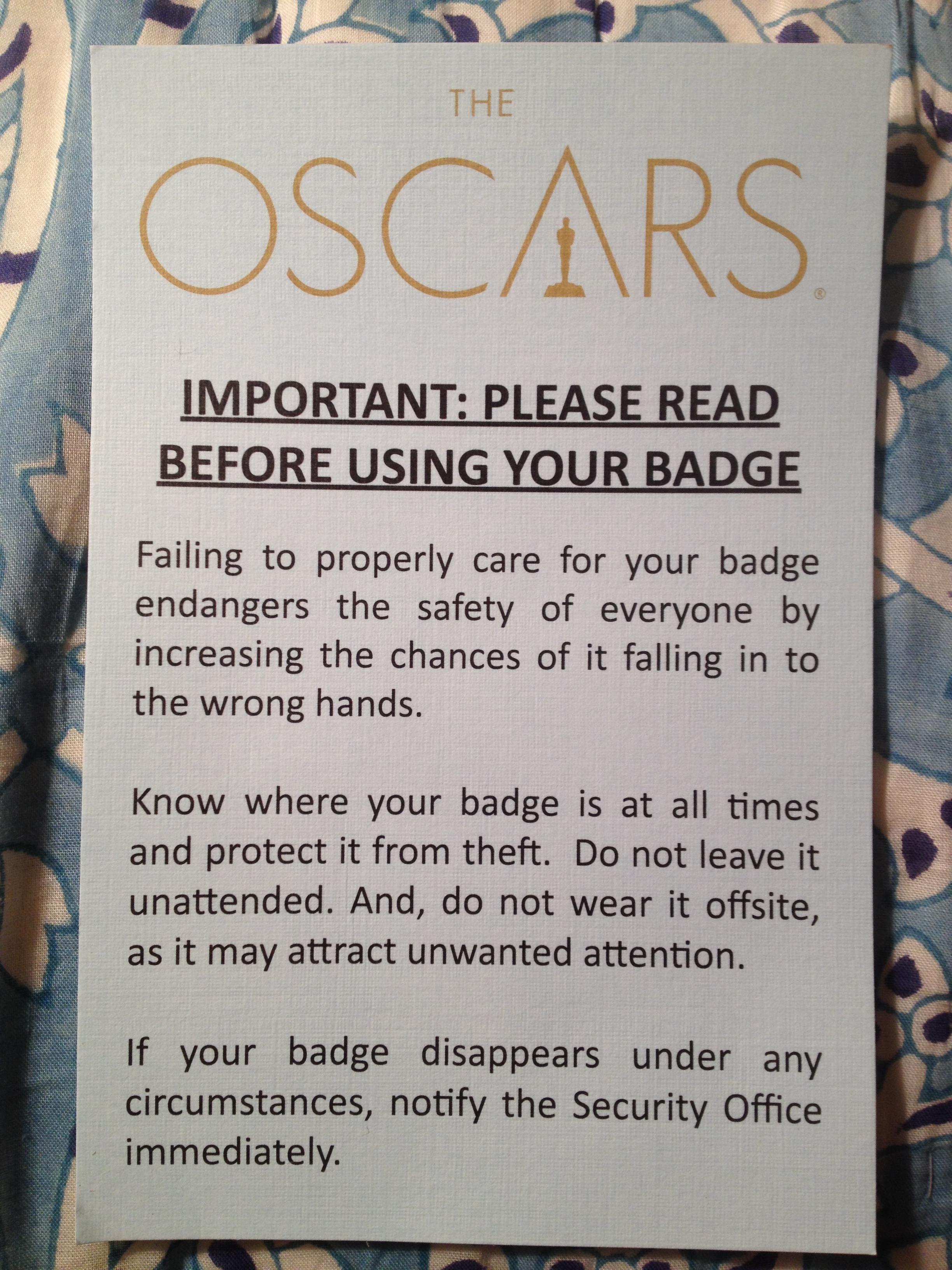

Just in case that reminder wasn’t sufficient, the people who printed out my badge also gave me two slips of paper, one of which rehashes my “press credential recipient responsibilities,” the other of which bears the admonition “IMPORTANT: PLEASE READ BEFORE USING YOUR BADGE.” I never knew badges required any special expertise to use. Especially badges that let people stand around an outdoor space while construction workers erect bleachers and roll out red carpets. Guess that goes to show how little I know about Hollywood.