Of the nine top-grossing films of 2013, seven were presented in 3-D. Of the nine nominees for Best Picture announced this morning, just one—Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity—was made for viewing through polarized lenses. Like Ang Lee’s Life of Pi—the only 3-D nominee for 2012—Gravity skidded through the voting not only as a function of its dazzling effects but also in spite of them. When Lee’s film came out, critics swooned over its psychedelic seascapes, then commended the director for his restraint. Roger Ebert, the most irascible of stereoscopy curmudgeons, was surprised to find that he enjoyed the movie’s use of three dimensions: “Although I continue to have doubts about it in general,” he wrote, “Lee never uses it for surprises or sensations, but only to deepen the film’s sense of places and events.”

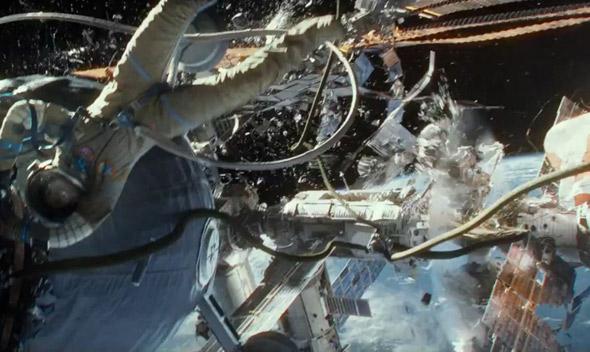

And so it is, to some extent, with Gravity. As a pure feat of filmmaking, no other nominee can match its reputation. (The movie was tapped for 10 awards in all, including best cinematography, directing, editing, production design, and visual effects.) But even as he’s praised for the stunning spectacle, Cuarón’s been judged to have a gentle touch. He’s not afraid to send things flying off the screen to wow and frighten us, but he also lets them drift in outer space to set the mood. Debris and solar flares emerge into the theater in the quiet moments, too—for ambience, not escalation. “I didn’t want it to be a gimmick,” Cuarón told io9. “It was just part of the experience.”

At several points Gravity even deploys pop-out in reverse, not to thrill us but to set us up. “We deliberately floated a Marvin the Martian doll into the audience space using significant negative parallax (the space in front of the screen plane) to give a moment of light-heartedness,” said Chris Parks, Cuarón’s 3-D maven. Moments later, the camera whips around to show a floating corpse. “Rather than making that shocking moment the time when we bring the 3-D out into the theater … we did something to alter the mood of the audience in the period immediately beforehand.”

Many of the finest 3-D films—or at least many of those nominated for an Oscar—share this trait: They use their pop-outs with discretion, or forgo them altogether. In Avatar, James Cameron made a point of leaving almost everything behind the screen, as if the edges of the frame formed a window on a large-scale diorama. That’s the classy way to use the medium, and what separates the artists from the entertainers. Clearly, 3-D will only shed its corny reputation—and have a chance of being “saved”—when directors learn to keep the cheaper thrills in check: No daggers thrust into the second row; no simple-minded fun.

It’s the broken windows theory of cinema: Crack the theater plane and you’ve opened up to deeper forms of degradation, dopey genre films and 3-D gore. But let’s not be short-sighted. This isn’t classiness; it’s prudery. Cuarón doesn’t harp on this rule of thumb, and neither should we. To do so makes the format slick and useful, like HD video or CGI. It dooms 3-D to respectability, and takes away its thrust.

The urge to render depth inert dates back to its early days. There’s a famous scene in House of Wax, the 3-D horror flick from 1953, where a tuxedoed tout speaks directly to the camera. “Come in, ladies and gentlemen,” he cries as he snaps a paddleball off the screen and into the viewer’s lap. “Thrills, chills, a lot of dirt!” In the early years, 3-D’s “eye-popping” special effects were often literal and self-conscious—and presented in a sheepish tone. It’s as if the films were scolding even as they pandered: Careful with this toy, they said, or you’ll poke your eye out.

Critics have long bemoaned 3-D sensation-seeking, too. “On a few occasions, such as a scene in which a barker bounces a rubber ball toward the audience or figures tumble forward in the picture, the shock effect is pronounced,” wrote the New York Times’ Bosley Crowther of House of Wax. “But the so-called added dimension of ‘deepness’ is of slight significance.” There’s a double-standard here, and one that afflicts even those who seem most open to the format. In other media, the pop-out effect—I mean the violation of the viewer’s space—isn’t always seen as something trivial or déclassé. It’s taken as a metaphor for the porous borders of the self, and a means for deep engagement.

I think of 3-D films every time I see the work of Bridget Riley, the op-art innovator who made her name with paintings that assault your eyes and tweak your brain. Like 3-D movies, Riley’s grids and patterns even make you seasick. “I wanted the space between the picture plane and the spectator to be active,” she said of her early work from the 1960s. Among the first of these window-breaking works was one called “Discharge” (later renamed “Static”) with which she hoped to batter the viewer “like arrows being discharged in your face as you looked at it.”

It was in its way a throwback to Fort Ti, a 3-D western from William Castle that had been shown in theaters not so many years before. Castle sent his flocks of flaming arrows right into the audience, along with blasts from muskets and from cannons. Now his film is minor camp, known mainly to 3-D completists. One of Riley’s “Static” paintings recently sold at auction for $2.9 million.

I don’t mean to say these works are similar; only that they’re not so different. Both describe the tension that exists between popping out and pulling in, between negative and positive parallax, between the gimmick of 3-D and the immersive atmosphere that it’s very able to produce. They don’t take sides and neither do they squirrel away—like most other films and paintings do—behind the viewing plane.

The best 3-D effects are those that play against this split, I think, and smash the window all to pieces. There’s a lovely one from 1983, in the otherwise insipid horror flick Jaws 3. One character swims down to meet the shark head on, and jabs his spear into the audience, a standard 3-D gag that maybe makes you wince. But when Jaws bites back the camera shifts, and we get a reverse angle from inside its mouth. Now the teeth are out in front, forming a serrated window of their own. There’s a pop-out here, but it’s not a pointy object. Rather it’s the blackness of the creature’s maw, merging with the darkened theater space, and then interrupted by the body of the diver as he’s chomped right through the screen. That’s a gimmicky effect, of course, but it’s also strange and sui generis, how 3-D should be.