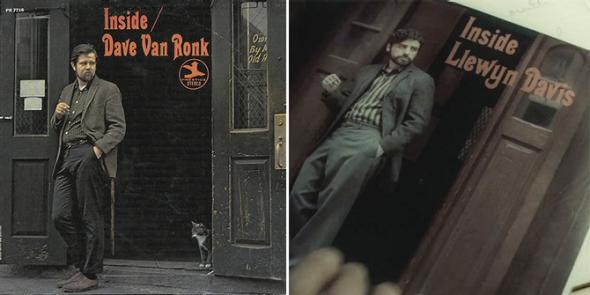

“OK, suppose Dave Van Ronk gets beat up outside of Gerde’s Folk City. That’s the beginning of a movie.” So Joel Coen once said to his brother Ethan; the result is Inside Llewyn Davis. Somewhere between idea and execution, Dave Van Ronk became the fictional Llewyn Davis, Folk City was conflated with another real-life Greenwich Village venue (the Gaslight Café), and the surrounding scene was populated with mostly made-up people.

But it’s not all pure invention. Here and there among the imagined scenes and fictional characters are real events (or something like them) and nods to notable figures. At least one supporting part is a rather thinly fictionalized version of an actual person. And throughout the movie there are allusions and in-jokes that are more fun and make more sense if you’ve studied up a bit on the New York City folk scene circa 1961. (Your best guide when it comes to Inside Llewyn Davis—apart from what follows, of course—is Van Ronk’s posthumous memoir, The Mayor of MacDougal Street, which the Coens have acknowledged as a source for their screenplay.)

Herewith a quick rundown of the people whose music and stories helped shape the new movie.

Dave Van Ronk

Photos via Prestige Records, CBS Films

Elijah Wald, who co-wrote The Mayor of MacDougal Street, has said of the movie’s lead, played by Oscar Isaac, “The character is not at all Dave, but the music is.” But the Coens borrowed more than a track list from Van Ronk. Like Llewyn Davis, Van Ronk was a folk and blues singer from the outer boroughs who made his living playing coffeehouses in the Village after a brief stint in the merchant marine. Like Llewyn, he considered abandoning music and returning to the sea, only to realize he had lost his seaman’s papers. Early in his career Van Ronk hitched to Chicago to audition for Albert Grossman at the Gate of Horn, a folk mecca, under the false impression that Grossman had received a demo of his. That event is the basis for a key sequence in Inside Llewyn Davis. Another scene, in which Llewyn goes to the man who runs his record label and asks for money, is a fairly faithful adaptation of a passage from The Mayor of MacDougal Street. Llewyn’s label, Legacy, is a nod to Van Ronk’s first, Folkways, a small outfit run at the time by Moses Asch. (Its name also recalls Tradition Records, another folk-centric enterprise, which folded in 1961.)

Davis and Van Ronk are different in many ways, of course; most notably, perhaps, Van Ronk did not begin his career as part of a duo. Llewyn, we learn, got his start performing with Mike Timlin, a fictional character who, oddly, shares his name with a pretty good relief pitcher. (If you have your own theories about that name, let me know in the comments.) The Coens have said they were also thinking about Fred Neil and Vince Martin, a ’60s folk duo who went their separate ways. (The latter is the subject of a recent documentary.)

Jim and Jean

Photos via YouTube, CBS Films.

The look of Justin Timberlake’s character, Jim Berkey, was lifted from Paul Clayton, a close friend of Van Ronk’s who committed suicide in 1967. Clayton, a dedicated folklorist, had (like Timberlake) a smooth singing voice and (like Van Ronk) was one of the Village folkies that Bob Dylan got some of his early material from. But Clayton was gay and unmarried, while Jim has a wife named Jean (Carey Mulligan). Those first names are borrowed, as the Coens have acknowledged, from the folk duo Jim (Glover) & Jean (Ray), one of several performing couples on the ’60s folk scene. (Jim & Jean, who were prominently featured on Art Linkletter’s TV shows, also helped inspire Mitch & Mickey, from Christopher Guest’s A Mighty Wind.) As Elijah Wald notes, Van Ronk never crashed on Jim and Jean’s couch, but another Village folkie, Phil Ochs, did. In the movie, Jean is pregnant, and Llewyn might be the father—which wouldn’t be a first for him. In MacDougal Street, Van Ronk, speaking of that time and place, says “there were pregnancy scares at least twice a month.”

Tom Paxton

Photos courtesy of Elektra, CBS Films

The name of Troy Nelson, played by Stark Sands, is surely a deliberate echo of Tom Paxton, one of the more successful singer-songwriters to emerge from this milieu. Like Paxton at the beginning of his career, Nelson is in the Army and living at Fort Dix, visiting the Village on weekends to perform at the Gaslight and elsewhere. The Coens leave little doubt about their inspiration here by having Troy sing “The Last Thing on My Mind,” one of Paxton’s best known songs.

Albert Grossman

The character played by F. Murray Abraham is less disguised still; the Coens didn’t even bother to change his last name. Bud Grossman, like his inspiration Albert, owns an important music venue in Chicago called the Gate of Horn. Davis goes to audition for him, as Van Ronk did for Albert, and Bud has the same “studied impassiveness” that Van Ronk attributes to Albert in MacDougal Street. At that audition, Bud mentions that he’s putting together a trio, and gauges Llewyn’s interest in trying out for it. Fans of ’60s folk will recognize this as a reference to Peter, Paul, and Mary, the trio that Albert Grossman put together in 1961—ultimately choosing Noel Paul Stookey as the third member of the group, rather than Van Ronk, whom he also considered. Such fans will also know that Albert Grossman became the manager of a singer who, though mostly unseen, shadows Inside Llewyn Davis from start to finish: Bob Dylan.

Peter, Paul, and Mary

Photo via International Talent Associates/Wikimedia Commons, CBS Films.

That scene with Grossman is not the movie’s only allusion to folk’s most famous trio. We also see Troy join Jim and Jean on stage at the Gaslight to sing “500 Miles,” a traditional song that was arranged by Hedy West but made famous by Peter, Paul, and Mary, who included it on their debut album. That album went to No. 1, helping to make the folk revival a major commercial phenonemon.

Doc Pomus

Photos via Clear Lake Historical Productions/Felder Family Archive, CBS Films

Roland Turner, the cantankerous hipster jazz musician played by John Goodman, has multiple inspirations, the Coens have said, including Dr. John—who, like Turner, was addicted to heroin in his younger days. But physically Turner most resembles Dr. John’s sometime collaborator Doc Pomus, the Brooklyn-born son of Jewish immigrant parents who went on to become a major R&B songwriter, responsible (with the pianist Mort Shuman) for such hits as “This Magic Moment,” “Save the Last Dance for Me,” and many more. The effects of polio required Pomus to use crutches (or, sometimes, a wheelchair) throughout his life, as Turner does in the movie. (A documentary about Pomus, born Jerome Solon Felder, was released last year.) Why is Turner’s companion, played by Garrett Hedlund, called Johnny Five? I have no idea. (Again, let me know your theories in the comments.)

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott

Photos courtesy Ramblin’ Jack Elliott/ANTI-Epitaph Records, CBS Films

Adam Driver (of Girls fame) has a fairly small part in Inside Llewyn Davis, but it’s a memorable one: He plays Al Cody, a cowboy hat-wearing folksinger whose real name, Llewyn learns, is Arthur Milgrum. Both the attire and the Western-sounding stage name (think Buffalo Bill Cody) recall Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, who was born (in Brooklyn) Elliot Charles Adnopoz. Elliott ran away to the rodeo at 15 and took Woody Guthrie as his mentor a few years later, so he could do the cowboy thing pretty convincingly by 1961 (the year he turned 30).

There are others whose presence is felt, however briefly, in Inside Llewyn Davis. The real-life folk musician Nancy Blake shows up in one scene, playing someone who, with her dulcimer-accompanied rendering of “Storms Are on the Ocean,” brings to mind Jean Ritchie. And the Clancy Brothers are evoked by a group of sweater-wearing Irish singers. But the movie is less about such one-to-one correspondences than it is about taking that entire milieu and placing a few wayward souls in the middle of it. Certainly, Dave Van Ronk, Paul Clayton, and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott never got together and sang anything half so silly as “Please Mr. Kennedy,” which the Coens (together with T Bone Burnett and Justin Timberlake) adapted from a song recorded by the Goldcoast Singers. But they probably all knew some people who did.