Coverage of The Kraus Project has focused, understandably, not on the somewhat obscure Austrian satirist for whom the “project” is named, but on the famous American novelist and Kraus superfan who put the project together: Jonathan Franzen. As Benjamin Nugent points out in his Slate review, the book is what Germans call a komischer Vogel, a “strange bird,” so much so that a writer of less standing could never get away with it: The book consists of English translations of two Kraus essays, plus their German originals, plus “footnotes to footnotes of footnotes” by Franzen, Kraus scholar Paul Reitter, and Austrian writer Daniel Kehlmann.

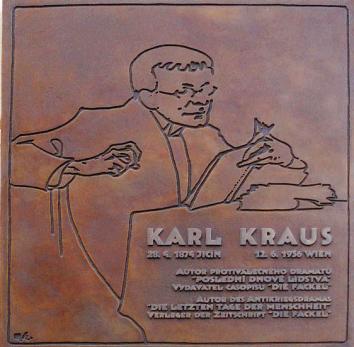

Because the annotations often overshadow the primary-source material—so much so that they become the primary-source material—critics are understandably taken mostly with them (and the various phenomena described therein which the crotchety American author clearly loathes). And because Franzen’s litany of grievances tests the boundaries of Schmäh (the Viennese art of relentless but affable taunting), readers may be put off enough that they throw Karl Kraus out with the Franzenwasser. So please know that I am employing Schmäh when I argue that missing out on this collection of essays would make you a Vollidiot: Kraus is one of the most uproarious and relevant writers who ever lived.

And you also shouldn’t let your newfound interest in century-old Austrians stop with Kraus. If someone that obscure can get Internet-famous in 2013—Kraus, whose corpus included the 200-scene play The Last Days of Mankind, which will likely transpire while you attempt to read it—then so, too, should his friends and associates, whose revolutionary (and sometimes insane) theories were as influential in such fields as architecture and philosophy as Kraus’s Fackel was in the milieu of cultural satire.

Among Kraus’s compatriots was—as Reitter (a former colleague of mine) points out in a footnote in The Kraus Project—the architect Adolf Loos, whose treatise Ornament and Crime compared the Hapsburgs’ rococo facades with the crude tattoos of convicted murderers, and insisted that civilization’s first true ornament, the crucifix, was “erotic in origin,” explaining: “a horizontal dash: the reclining woman; a vertical dash: the penetrating man.”

Even more controversial than Loos was the philosopher Otto Weininger, whose Sex and Character argued that femininity was not only an immutable characteristic, but that females had exactly one goal: as much sex as possible, whether it be for procreation or recreation. Feminine individuals—among whom the gay, Jewish Weininger placed both Jews and homosexuals—were so morally bankrupt as to be “amoral,” incapable of even the most basic attempts at logic or reason. Before committing what he believed to be an ethically victorious suicide 23, Weininger attracted the accolades of many of Vienna’s intellectual elite—including, alas, Karl Kraus.

Then there was the cultural critic Peter Altenberg, who was such a fixture at Café Central that he got his mail delivered there—and the composer Arnold Schönberg; the artists of the Secession; the philanthropist-cum-ascetic-philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and his fabulously wealthy (and famously troubled) family. Karl Kraus was just the beginning: Vienna at the turn of the 20th Century was a culture of near-incomparable per-capita craziness, whose artifacts linger both in “quiet permanence” (as Franzen would say) and, mercifully, all over the Internet. It would be a shame if the Franzenfreude surrounding this publication ended up alienating American readers from the very Viennese brilliance Franzen wants to show them.