And here I thought my graduate philosophy seminars were intense: This past Sunday in Rostov, Russia, two young men, passing time in line to buy beer, began a discussion of Immanuel Kant, harbinger of the German Enlightenment. The conversation ended with one shooting the other repeatedly with rubber bullets. In reaction, the Russian-born philosopher Anna Alexandrova deadpanned to me on Facebook that the incident highlights “two beloved Russian habits: deep conversations over alcohol, and using intellectual and spiritual pretexts for violence, just like Dostoyevsky’s characters loved to do.”

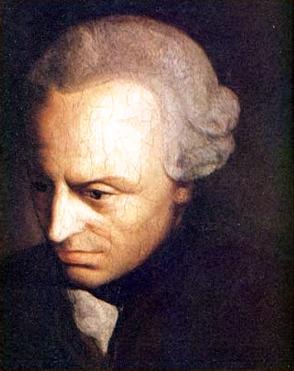

But if you are under the impression that the Rostov incident is an extreme example of Kant’s injurious influence upon humanity, you are mistaken: The Kremlin Kerfuffle is but another chapter in a long, storied history of adverse reactions to the giant-foreheaded Angesicht (“visage”) of the Enlightenment, whose major work, the Critique of Pure Reason, had passionate detractors from the moment of its first edition’s publication in 1781.

Kant argued that human reason operates by way of “forms of intuition,” such as space and time, and “categories of the understanding,” such as causality. His friend Johnann Georg Hamann, a philosopher, theologian, and terrifying polyglot, took that to mean that intuition and understanding predate human language. He found this so objectionable that he published a counter-screed called Metacritique of the Purism of Pure Reason, and insisted that human language is the source (Quelle) of understanding, not its result, and, with utter seriousness, that language is obviously a poorly approximated “translation” from “angelspeak” (Engelsprache). Hamann, Johann Gottfried Herder, and their associates comprised an amorphous “Counter-Enlightenment,” whose only common purpose was to prove Kant wrong.

But Hamann’s colorful, analogy-filled jeremiads paled in comparison to the reaction of author Heinrich von Kleist (Michael Kohlhaas, The Marquise of O). The Critique of Pure Reason argues that everything we can know resides in the “phenomenal domain,” and that reality independent of how we experience it—what Kant referred to with the unfortunate German word salad Ding-an-sich—is part of the “noumena,” along with other transcendental stuff unknowable upon this mortal coil: God, the Essence of the Soul, etc. Kleist understood this to mean that anything he took for “true” was not absolute, objective truth, but merely an approximation dependent entirely on his fallible senses—that he might as well “have green glasses for eyes,” but insist the whole world was green. Since the entire purpose of Kleist’s life had been a search for pure truth, that life was now meaningless. The only feasible option was to take his terminally-ill girlfriend Henriette Vogel down to the shores of Berlin’s Wannsee and usher them both, via non-rubber-bulleted shotgun, into the noumenal realm prematurely. As murder-suicides couldn’t be buried in consecrated ground, both Kleist and Vogel still rest by the Wannsee, a morbid tourist attraction in an area rife with them.

Anti-Kantianism would go on in subsequent years to be a conclusion so foregone that Bernhard Bolzano and Franz Prihonsky’s 1850 Neuer Anti-Kant had to distinguish itself philosophically from the older Anti-Kants that came before it. Meanwhile, lieber Immanuel was one of Nietzsche’s most vitriolically targeted “gay scientists,” largely responsible, via the definition of God as “noumenal,” for hastening His demise—and what’s more (and possibly worse), coming up with the Categorical Imperative, a universally applicable maxim of morality Nietzsche decried in The Antichrist as idiotic.

In “An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?” Kant cautioned that unbinding a yoked people unable to exercise reason freely would take effort and time. Judging from the Rostov melee, that’s 232 years and counting.