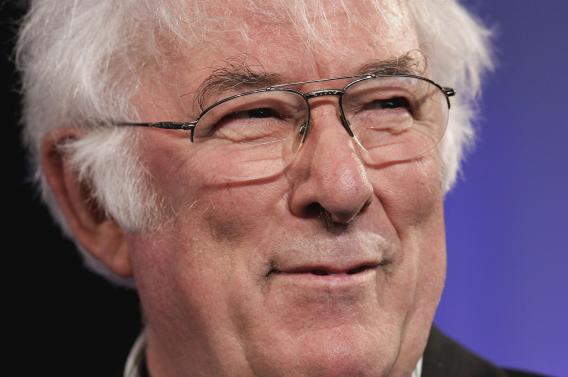

In 1996, I asked Seamus Heaney if he could please send me a poem for a new magazine to be called “Slate.” It was a weird request, it took some trust on his part. For one thing, the word “magazine” would be in psychological quotation marks, and the phrase “Internet magazine,” for that man, in that year, had to sound like babble.

Like many of the poet friends I recruited, Seamus didn’t much understand how a magazine could exist not on paper but on something called The Internet. Like nearly all of them, he had never used a computer.

But characteristically, Seamus responded to my request right away, and generously. The poem he sent me (by mail) appeared in Slate’s first issue and it is a beauty: “The Little Canticles of Asturias”—a wonderful account, in three stanzas, of a drive in Spain.

The three stanzas also make a capsule version of Dante’s Commedia. First stanza, at midnight, infernal trash fires and hot refineries making an “epic blaze” on “the hellish roads.” Second stanza, the purgatorial “next morning,” and “I felt like a soul being prayed for” as families in roadside fields “wave at me from their other world.” Third stanza, the paradise of rivers in sunlight, a reference invoking the sainted poet San Juan de la Cruz and the poem’s closing lines, droll as well as ardent:

in the great re-echoing cathedral gloom

of distant Compostela, stela stela.

That tripling echo, in the final syllables, also echoes the Italian stelle (stars), which Dante makes the final word of all three canticles of his Commedia. The innocent mischief of this nervy literary reference. A mischief on the side of the irreverent literary angels, not the pedantic ones. There should be a word for such a reverse parody—mocking oneself in a tribute to a great predecessor: a maneuver demanding immense grace and masterful poetic chops.

The Dante reference of “The Little Canticles of Asturias” has an additional, personal echo for me. He chose this poem for what must have seemed like a bizarre, arcane venture in computer-land, with, I think, a personal touch. Before committing myself completely to the translation that became my Inferno of Dante we spent a morning together at Seamus’s house in Cambridge, going over my notes and drafts—and his. His 1994 book Field Work has a brilliant re-setting/translation of the Ugolino passage, incorporating Dante’s vision into Northern Ireland and its troubles. At the end of our session, he told me to do the Inferno and—his practical side, salting his generosity—Do it quickly, he told me.

When considering the lives of writers, an unpleasant truth emerges: Many of them, including some great ones, were mean or petty or worse. I’ve often thought to myself, Thank god for Chekhov, who demonstrated that a great writer could be generous, large-hearted, unselfish, tolerant.

The same goes for Seamus Heaney: His understanding of other people, individually and in groups and in nations, made him a master of occasions and a supreme teller of jokes and stories. The same quality makes him a great poet. Thank god for him, too.

Elsewhere in Slate, read Katy Waldman on the legacy of Seamus Heaney, and watch Heaney himself read his famous poem “Digging” through the years.