In this high summer edition of our quest to dispel the mysteries of the modern visual landscape, we’re heading out west. For previous columns, click here; to submit your own suggestions, email us.

If you’ve ever traveled to Wyoming, lucky you. Here you can dodge geysers in America’s first National Park, traipse around America’s first National Monument, or shoot the breeze (and the neighbors) with the Cheneys. You could visit Cody, the town that Buffalo Bill helped found (it’s also the birthplace of Jackson Pollock). Or you can simply bask in the radiance of the first state—and the first constitution in the world—to explicitly grant women the right to vote. (Official nickname: The “Equality State.”)

Still, you’re probably here for the scenery. Wyoming’s beauty is its mountains, and its (very) High Plains. The state’s mean elevation is second only to Colorado’s, and the lowest point in Wyoming is loftier than the highest points of 17 states.

Then there’s what I remember most about my drive there years ago: the stunning emptiness. This is America’s least populated state, and, aside from Alaska, the least densely populated. Amid that emptiness are the roads, which—like the state’s borders, all four of which are lines of latitude or longitude—at least appear beautifully straight. These are roads that every American can take particular pride in: The state receives more federal dollars per capita than any other, again aside from Alaska.

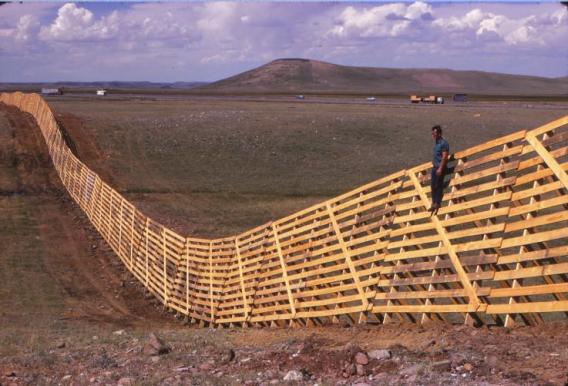

On the sides of some of these great American byways, you may notice fence-like structures, shown above. What are they for?

You might reasonably think it has something to do with livestock. Wyoming’s state seal features a cowboy; the state flag bears a bison. And what you’re looking at is indeed a fence—but it’s not for ungulates.

It’s for snow. And if you drove down Interstate 80 in the winter, you can thank fences like these for helping keep the highway as clear as it probably was.

The coolest thing about snow fences, though? They’re not designed to “catch” blowing snow—in fact, they’re not really a barrier at all in the traditional sense. Instead, the slats of the fence slow down the wind as it passes through. And the wind then drops some of the snow it’s carrying.

This means that most of the fence-conjured snowdrift accumulates downwind of the snow fence—i.e. after the wind and snow have passed through. Neat, huh? (The good people at Iowa State can tell you everything you wanted to know about how snow fences work.)

Courtesy of Government Engineering Journal

Snow fences have lots of uses in wintry, windy places. They can protect railway lines and airports (like Denver’s). Ski resorts can use them to gather snow, and ranchers can lock in a spring water supply. There are “natural” snow fences, of vegetation—and sand fences, too, that use the same principle to control blowing sand.

Snow fences have an ancient history; one of the earliest may have been at Stonehenge. But in America, the modern history of the snow fence is particularly tied to Wyoming, and to one road, I-80, and to one man: Ron Tabler. I’d be surprised if anyone has had a longer list of snow-related publications. Tabler died in 2010, but his son, Ed Tabler, filled me in on his father’s long quest to save the money, time, and lives of motorists.

Ron Tabler

When I-80 opened through Laramie, it was a treacherous stretch of road in the winter; accidents were common, as were fatalities…it often had to be closed. It became known as the Snow Chi Minh Trail. It was so infamous that state politicians were lobbying to have the highway permanently closed and relocated.

My dad became fixated on the science of blowing and drifting snow. He studied everything from particle physics to evaporation. He modeled how snow drifted behind bushes, concrete blocks, wooden posts, you name it. He built miniature snow fences with different heights, bottom gaps, porosities, and placements. He then developed equations that would predict the shape and size of snow drifts. Much like a storm chaser, whenever the weather turned ugly, he’d hop into his Suburban and drive into the storm, taking road temperature data and video.

How effective are snow fences? First of all, they reduce snow clearance costs by keeping snow off highways. According to data from 2005, traditional snow removal can cost about $3 per 2,200 pounds, while a 4-foot-high snow fence can catch 8,400 pounds of snow for each foot of length. Plowing, of course, needs to be repeated, while a snow fence, properly maintained, will keep on working. One early ’90s study put the cost of plowing snowdrifts in windy areas at around 100 times the cost of snow fences.

Snow fence

Ron Tabler

Snow fences also reduce the need for sanding and salting. Blowing snow is a big cause of ice on roads, because it melts onto surfaces that have been cleared, stealing the solar heat such surfaces may have absorbed during the day. (Road surfaces protected by snow fences routinely stay about 15 degrees warmer than unprotected roads.) Snow fences also cut down on road maintenance: Snow damages roads by blocking drainage, and salt and plows damage roads further.

But the best reason to invest in snow fences is that they save lives. A lot of this comes down to improved visibility, because snow fences keep snow from blowing across roads. When snow fences were installed on sections of Interstate 80, the portion of accidents that occurred in blowing snow dropped from 25 percent to 11 percent. Snow fences also keep roads clear of snow, ice, and slush, which further reduces accidents. In fact, snow fences easily passed a cost-benefit analysis based solely on accident reduction, without even factoring in savings from snow clearance and road maintenance.

So there you go. Wherever you’re next going in Wyoming, whether to the Cheneys (careful!) for Thanksgiving, or for Yellowstone in the winter, keep an eye out for snow fences. They’re a monument, as Ed Tabler eloquently put it, “to good engineering and lives saved.” And, I’d add, to his father.

Until then, if you spy something mysterious out there looming through the sultry August haze, send a pic and description to whatisthat@markvr.com.

Another snow fence, minus the snow

Ron Tabler

Previously in What’s That Thing?

Doorway Symbols

Tin Foil Secret

U-Shaped Toilet Seats

City Steam

Lump on a Wire

Convenience Store Strips

Wall Socket Buttons

Elevator S Button

Dashboard Arrow

Mysterious Wires