After a long period in limbo, Bunheads is officially no more. ABC Family canceled Amy Sherman-Palladino’s little-show-that-seemed-like-maybe-it-could-but-ultimately-couldn’t yesterday, showering it with every compliment but the one that really matters: more episodes. Kooky, lovable, verbose Bunheads, the story of Michelle (Sutton Foster), a screwed-up dancer with a knack for screwball dialogue who gets a shot at the more grown-up, fulfilling life she never ever imagined for herself by teaching ballet to a group of junior screwballettes, was canceled because of its low ratings, which is just the dry way of saying it was canceled because it was different—too unique and unconventional to attract a sizeable audience.

Bunheads was unlike any other show on television, and not just because it regularly contained dance sequences inspired by recycling or the horrible mood of a surly teenage girl. Its obsession with talking as a way of drawing people in while keeping them at a distance; its very la-di-dah attitude toward plot; its slow-burn approach to heavy themes like failure and maturity and grief; all these made it special—and a little weird. Bunheads had absolutely no interest in conventional “stakes”—highly dramatic events that keep an audience invested, episode after episode—and contained almost no violence, horror, or soap opera-like plot devices. Instead, Bunheads got its charm and emotional punch (if never that much forward momentum) from juxtaposing mile-a-minute dialogue with the snail-like pace at which real change occurs.

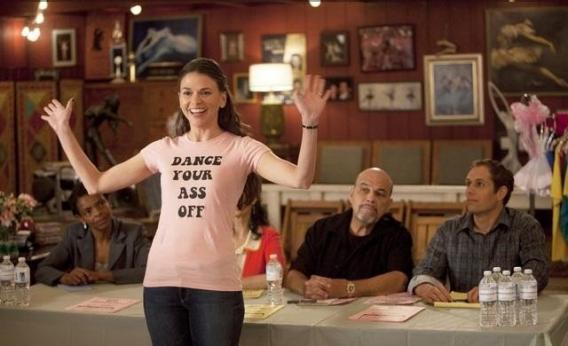

Bunheads began when Michelle, a classically trained Vegas dancer whose ambitions had come to naught, agreed to marry a sweet, doting guy, Hubble, who’d been chasing after her like a puppy dog. He took her home, to the California town of Paradise and the house he hadn’t told her he shared with his mother Fanny (Kelly Bishop), and promptly died in a car accident. Instantly Michelle’s fantasies about who she could be—her harebrained attempt to right her course—exploded in her face. In her late 30s, faced with various unpleasant options, Michelle stayed on in Paradise despite her initially fraught relationship with her mother-in-law. And over the next 18 episodes, slowly and sometimes painfully, she learned from the women around her how to be an adult, a part of a family, and a teacher. Michelle began the series refusing to teach class—those who can’t do, teach, after all—but by the end was the show’s quartet of girls’ most trusted grownup, honored with and obligated by their secrets and concerns and questions about sex. Turns out those who can’t do, do teach, but is that so bad? It may not have been Michelle’s dream, but it gave her a life.

This arc—both melancholy and hopeful, about what happens after the unhappy ending—was the solid substance that undergirded a show that could be quirkier than the quirkiest late-’90s Sundance flick. Watching Bunheads was to be inundated with zany characters—the autocratic coffee-brewer/artiste, the spazzy dressmaker, the high school twins perfect at everything—and lively, dense, often hilarious, sometimes infuriating dialogue. This dialogue often had no bearing on plot, but was whatever struck Sherman-Palladino’s fancy: extended, reference-packed riffs about muffins or a town called Oxnard or some reality TV show. You either had to submit and luxuriate in it, or it would drive you crazy with its seeming irrelevance.

It’s not that Bunheads was a show scared of silence. Almost every episode contained a wordless sequence, Michelle all alone, a dance, or one my favorites, the gorgeous scene in which the girls educate themselves about sex. It was the characters, and Michelle in particular, who were scared of silence. Michelle talked and talked and talked and Fanny talked and talked and talked because it was through yammering that they were building their connection, a connection too fragile to actually talk about. Talking about anything really freaked Michelle out. Usually it made her run away. In the premiere of the second half of the first season—such were the milestones of a show perpetually almost-canceled—after Michelle had fled Paradise because she accidentally pepper-sprayed kids trying to dance in The Nutcracker, Fanny had to go get her and explain that all the yelling and fighting didn’t mean that she had wanted Michelle to leave forever. When Michelle returned, she walked into her house only to be bear-hugged by Sasha, the wonderful dancer and sometimes sullen cool girl who like Michelle had negligent, awful parents, but unlike Michelle, at least had Michelle.

The bonds between Fanny and Michelle and Michelle and Sasha were just two of nearly a dozen different female relationships showcased on the series, most of which were strong and sustaining in their own complicated, slightly dysfunctional ways. While distracting audiences with all that unending verbiage, Bunheads carefully, methodically made the connections between these characters so powerful that by the end of the show’s first and only season they already seemed strong enough to tether Michelle to this town and these people—even if she didn’t know it completely yet. Among the many things that slay me about the show’s very last scene, in which a girl named Ginny (Bailey Buntain) confesses to Michelle that she has lost her virginity to a guy she thinks doesn’t knows her name, is that before doing so, Ginny asks Michelle, who has had quite a day, if she’s OK, and only after that breaks down in her arms. Michelle, not quite willingly, let herself be cared about by all these women, and found that she could and did care about them in return. It came sooner than it should have, but that’s not a bad ending.

Previously

Why Bunheads Is the Best Show on TV