When Edith Windsor learned that the Supreme Court had upheld her challenge to the Defense of Marriage Act on Wednesday, her first words were, “I wanna go to Stonewall right now.” Sure enough, the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street was the center of the New York gay community’s celebrations.

Nowadays, the riots that broke out at the Stonewall in the early hours of June 28, 1969, serve as the before and after marker in the gay liberation movement, one of the first occasions when gay and lesbian bar patrons stood up to police harassment. But we shouldn’t forget that the bar was, in the words of writer Vito Russo, “a regular hell hole. The pits.” A Mafia-run establishment, it was filthy and exploitative, and customers were treated shabbily. For the most part, that’s how things were in New York City during the late 1960s, when the legal status of bars serving homosexual patrons was uncertain.

But uptown, there was a place where gay men, at least, were treated like kings: the Continental Bath & Health Club at 74th and Broadway. Steve Ostrow, Brooklyn-born and dreaming of a career as an opera singer, was married—to a woman—when he opened the Continental. He’d pioneered interstate loans by mail, which led to his being charged with mail fraud. Although the case against him was eventually dropped, he spent seven years with “the federal thing” hanging over his head. Unable to operate his finance company or take singing jobs overseas, he looked for something closer to home. When a friend suggested that he invest in a gay bathhouse, Ostrow and his wife staked out a rival business. Standing outside the Everard Baths—described in the 1971 edition of The Gay Insider as having “scabby walls, [a] rancid pool and putrid-smelling steam room”—they saw 60 men entering every hour, day and night.

With money borrowed from his father-in-law, Ostrow opened an establishment that would respect its clientele and provide facilities they could be proud of: an indoor pool that Ostrow claims was the largest in the world at the time, a sauna, a steam room, an upscale restaurant, a hair salon, a boutique, a disco in which towel-clad men danced 24 hours a day, a room that held religious services on Friday and Sunday nights, and the spaces it was best known for, 400 individual rooms and two large orgy rooms—one with lights and one that was kept in almost complete darkness—where men could screw with complete abandon.

The story of the Continental Baths, and of Steve Ostrow, is told in Continental, a fascinating new documentary that premiered at South by Southwest in March and makes its New York debut tonight at BAM on the 44th anniversary of Stonewall. Directed by Malcolm Ingram, who has made two other documentaries about the gay community—Small Town Gay Bar, about community watering holes in rural Mississippi, and Bear Nation, about gay dudes who prefer gay dudes who are big and hairy—Continental isn’t a flashy production, but it packs a lot of forgotten history into its 85 minutes.

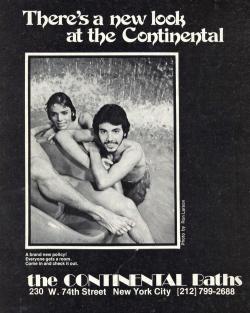

An undated flyer for the Continental Baths.

A few archival photographs and a cast of talking heads—former Continental patrons and writers Edmund White, Michael Musto, and Patrick Pacheco; activist-turned-archivist Rich Wandel; a handful of men who worked at the Continental, including the “Godfather of House Music,” Frankie Knuckles; several women who performed there; and Ostrow himself—make the case that the Continental was different. There’s no attempt to hide the lascivious nature of the place—it was a temple of hedonism—but Ostrow also notes that he installed a health clinic in the Continental, where men could get tested for STIs. (Although the Continental operated between 1968 and 1975, the documentary covers the period 1968-72, and Ostrow takes pains to stress that he was out of the sex business before the arrival of AIDS.)

The second half of the film focuses on the entertainers that Ostrow brought to the baths. As Michael Musto puts it, “It was a bizarre mixture of activity that you could enjoy once you set foot in that place. You could check your clothes, get fucked, suck like a madman, and then think, ‘Oh, I think I’ll see a nice little show.’ ” The most famous entertainers to emerge from the Continental were Bette Midler, Barry Manilow, and Labelle. Midler made the place famous by mentioning her shows at the gay bathhouse on Johnny Carson, but since she clearly refused to participate in the documentary—several people suggest that she abandoned the gay community once she hit the big time—and since the only footage of her performing at the Continental is insanely blurry, that section starts to drag.

Eventually, it was Ostrow’s desire to draw a straight crowd to see his entertainers that spelled the end for the bathhouse. As Edmund White notes, when heterosexuals came to the Continental, “it de-demonized gay life for many people” just as “it gave an alibi to many closeted gays to go to a gay place.” But for many of those straight visitors, staring at the gays in their towels was part of the show. That wasn’t necessarily fun for the old patrons. “They wanted the full-on hedonistic experience,” Musto remembers. “They didn’t want to be gawked at all night.”

Ostrow eventually came out as gay (he claims his wife was “frigid” after the birth of their children but that she was happy for him to have sex with “pretty boys”; she spent her last 10 years as a nun) and moved to Australia, where he finally achieved his dream of becoming a professional opera singer. In his new home, he founded the world’s largest organization for older gay men.

In 2013, as Michael Musto puts it, “The Continental almost seems like Brigadoon.” Stonewall is the name that everyone remembers—and, since there is once again a gay bar in that location, patronizes—but it’s possible that for one gender at least, the Continental is the place that really deserves the fame. This movie makes that case.