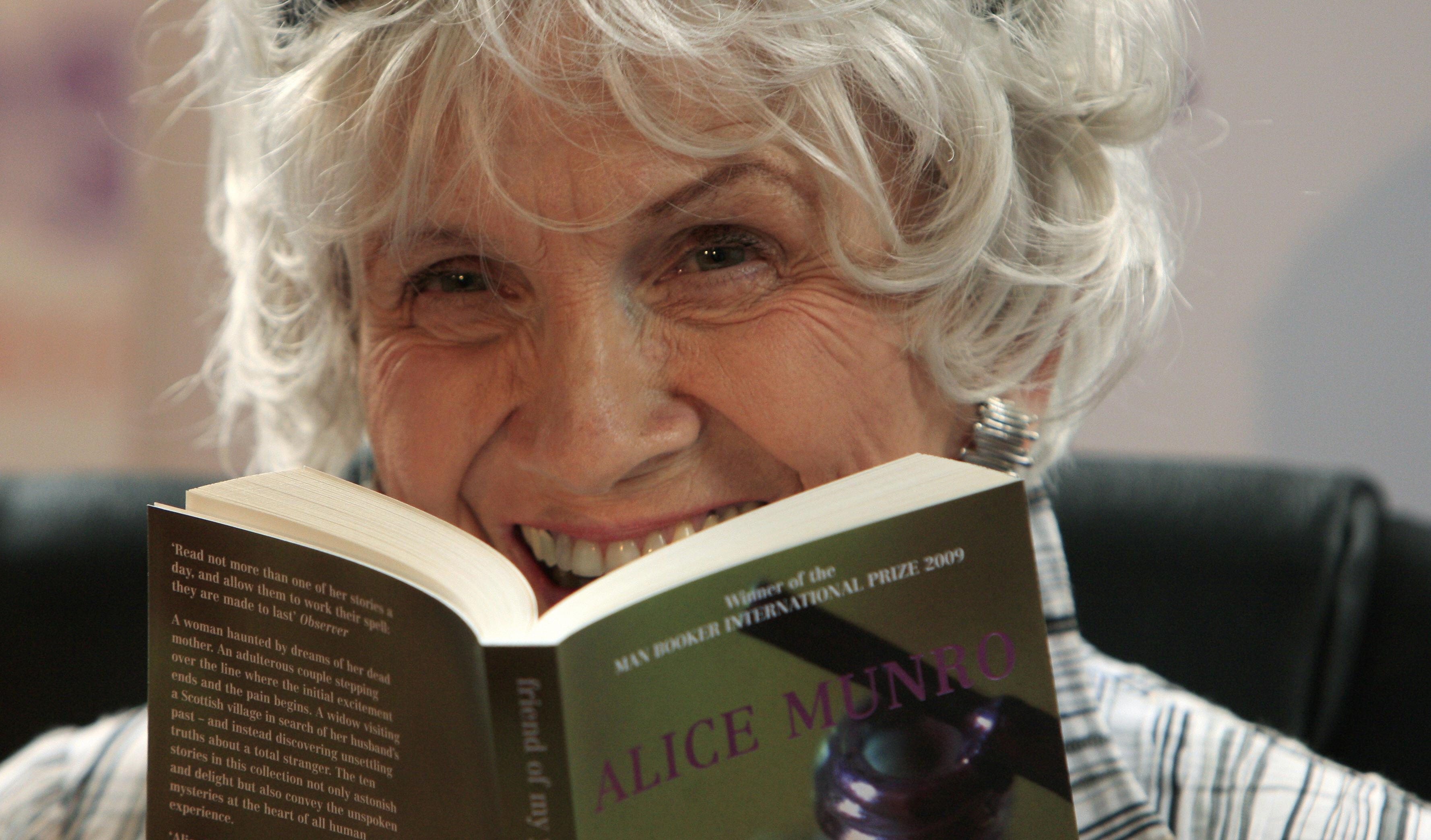

On Tuesday, the writer Alice Munro won Ontario’s Trillium Book Award for her latest, Dear Life. Then, in a genial interview with the Canadian National Post books editor, this happened:

Post: You’ve spoken about how Dear Life is the most autobiographical book you’ve ever written, especially those last four stories. Does this make winning more special?

Munro: I guess so. And a little more special in that I’m probably not going to write anymore. And, so, it’s nice to go out with a bang.

How many bangs are in that bang! She meant the award, certainly, but just as easily she might have been referring to what may now be her final story, the titular “Dear Life,” which closes the book, and which, fascinatingly for Munro-watchers, had been filed under the nonfiction heading “Personal History” on its initial appearance in The New Yorker, in 2011—and which left me, upon first reading, sitting still with the magazine on my lap for half an hour, my mind processing, processing, like an old IBM trying to churn large primes.

Bang. That’s the appropriate response to Munro’s best work, in which even the experience of revelation—what truths from the past can be discerned and which can’t, what lies can be discarded and which must be held forever—becomes a puzzle, a hall of mirrors. I return again and again to the story “Family Furnishings,” in which a woman determined to forge her own way learns—oh, it’s too much to say what she learns, or what we learn. It’s always too much. But one line in particular I carry with me, a line that comes when the narrator realizes that a new bit of knowledge is about to arrive, whether she likes it or not: “Now. I could feel it coming now.” My brain stem quivers every time. Barely stylized—just that little repetition of now—it is, in context, as chilling as the climax of a horror film. Wisdom delivered like a knife to the chest.

And now this final bang: that there may be no more Munro stories. But I’m OK with it—more so, I’m surprised to say, than the similar report of Philip Roth putting down his pen. (Roth is 80, Munro 81.) It’s hard to explain. With Munro—and this may have to do with her focus on short stories—even if she writes no more, I feel like she has already provided everything we could ever want from her, and that what’s left is my effort to unfold and unfold the papered-over minds of her characters, minds that unfailingly turn out to be my own.

Fiction in the realist mode is too often described as having characters and events that are “lifelike,” or “that feel real,” or “come off the page.” There is no “like”-ness when it comes to Munro. Only the real thing.