Since Bob Dylan arrived in Greenwich Village in 1961, he has been playing hide and seek. When people try to figure him out he disappears, or puts on a hat and makes a funny face, or knocks over a lamp so he can’t make a break for the back door. At age 72, he’s still doing this.*

This week, Open Culture posted a radio interview from the early days of Dylan’s career, which was uploaded to YouTube last fall. It feels like a nature documentary. Here we see the young Robertus Zimmeratus for the first time in his natural habitat. In February of 1962, Dylan sat in one place long enough to record a program called Folksinger’s Choice with Cynthia Gooding. It was a year after the famous New York Times review that had “discovered” Dylan, but weeks before the release of Dylan’s eponymous first album. Gooding, 17 years his senior, was an established folk singer also from Minnesota. What takes place over the next hour is a mix of flirting and music and the emergence of all the elements of the Dylan personality: the storyteller, the thief, and the virtuoso.

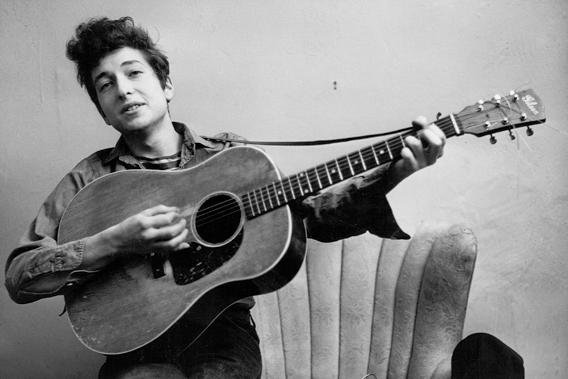

When Dylan finishes his first song, “Lonesome Whistle Blues,” Gooding is already in awe. “That was Bob Dylan. Just one man doing all that.” She’s mystified by the “necklace,” she calls it, that he wears around his neck so that he can play the harmonica while he strums his guitar. He looks like a lost, jumpy little kid, almost puppy-like, and then sings like a man twice his age. This is the tone of the entire interview, and it’s what made Dylan so fascinating during this period: There’s more in there than there possibly should be.

There are other radio interviews from this period, but this one is more a flirtation. Dylan is not yet the put-on artist of a few years later who embarrasses interviewers. He’s more like Benjamin Braddock here answering Mrs. Robinson. “It’s one of the greatest contemporary ballads I’ve ever heard,” says Gooding after Dylan plays “Emmitt Till,” the story of a young black man from Chicago killed in the south. “It’s tremendous.” She doesn’t stop there. The transcript, provided by the fantastic Dylan fan site Expecting Rain, captures the exchange:

Bob Dylan: You think so?

Cynthia Gooding: Oh yes!

Dylan: Thanks!

Gooding: It’s got some lines that are just make-you-stop-breathing great … It makes me very proud.

Dylan mumbles, “I try to keep it working.” Just before he starts into another song, she says, “That’s fine,” with such a sense of release it’s like she’s exhausted herself.

Dylan plays 11 songs between conversation, uncorking a raw, howling, soulful voice, and some rich passages of guitar picking. He plays songs from Howlin’ Wolf, Woody Guthrie, and Big Joe Williams. There are only three Dylan compositions, which are somewhere between original songs and thefts.

Throughout his career Dylan has been accused of stealing. Joni Mitchell famously called him out: “Bob is not authentic at all. He’s a plagiarist, and his name and voice are fake. Everything about Bob is a deception.” Well, yes. That’s his thing. The deception is on display throughout this interview, but he also is frank about the “borrowing” that he has always considered a part of the folk tradition.

I stole the melody from Len Chandler. He’s a funny guy. He’s a folk-singer guy. He uses a lot of funny chords you know when he plays … Well, he played me this one. Said ‘don’t those chords sound nice? An’ I said, they sure do, an so I stole it, stole the whole thing.

You can borrow and still make it your own has been Dylan’s defense—though after he’s done playing, he does seem a little sheepish about pinching the melody. “Just wait till Len Chandler hears the melody though,” Dylan says after Gooding compliments him. She lets him off the hook: “He’ll probably be very pleased with what you did to it.”

From the minute Dylan stops playing until he picks up the guitar again, you can feel him attracted to Gooding, anxious for her approval, and desperate to keep the whole exchage on his terms. His entire career, Dylan has tried to avoid the assessments and labels of his critics and fans. It’s why he has had almost a dozen distinct identities and stages. He won’t let Gooding call him a folk singer. Every time she tries to pin him down, it’s like she’s trying to make him wear an itchy coat. It’s not long before simple questions leave him looking for an exit. “You’ve been writing songs as long as you’ve been singing,” she asks. “Well, no. Yeah. Actually, I guess you could say that. Are these, ah, these are French ones, yeah?” Dylan is suddenly talking about her cigarettes. “No, they are healthy cigarettes. They’re healthy because they’ve got a long filter and no tobacco.” Dylan: “That’s the kind I need.”

Dylan’s favorite tic is making up passages from his biography. He talks about living in South Dakota and his six years with the carnival. Almost none of it is close to the truth. She presses him on how he could have been with the carnival for six years and also be the college kid she first met in Minnesota. “Well, I skipped a bunch of things, and I didn’t go to school a bunch of years and I skipped this and I skipped that.” You imagine that by the end of this exchange, Dylan has climbed up on top of the dresser looking for some kind of refuge.

But then we see an essential Dylan truth: It doesn’t matter if he was really in the carnival or not, because he can inhabit whatever world he said he’s from. Dylan launches into the most baroque tale of the hour, about his friend the “elephant lady,” an earnest, 500-word monologue about a carnival “freak,” who has two personalities, the one who wants your sympathy so that you’ll pay for the show and the postcards she is selling and the one who doesn’t need your pity. He talks about transferring that point of view into the narrator of a song. Oh, but he’s lost the song and can’t sing it. The whole thing sounds like an insight and a dodge at the same time.

This week Dylan announced yet another leg in his never ending tour. He’s following up his summer tour of America with a return to Europe, including three shows at London’s Royal Albert Hall. Forty-seven years earlier, it was at Dylan’s “Royal Albert Hall” concert (actually recorded at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester) that an audience member shouted out “Judas!” when Dylan switched to playing an electric guitar.* It was a famous revolt. In 1966, they wanted him to be the folk singer in that 1962 interview. But he wasn’t even a folkie in that interview—and if the audience had heard it, they would have known that Bob Dylan was never going to stay in one place for too long.

* Correction, 12:16 p.m.: This post originally misstated the year that Dylan arrived in Greenwich Village. While he met Gooding in 1959, he did not hit the Village until 1961. Also, he is 72, not 73, as the post originally said. Finally, Dylan’s “Royal Albert Hall” concert was actually recorded at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester.