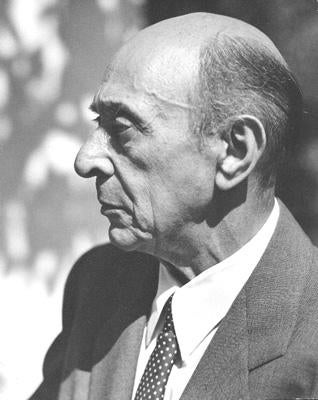

As someone who has studied and grown to love that post-1900 stuff we lump together as “modern classical music”—and has watched as loved ones glaze over at concerts I have dragged them to—I get it: Modern music is weird. The aesthetic criteria we’re used to applying to music—beauty, harmony, tunefulness, symmetry, etc.—do not necessarily apply, and indeed, are often the very things modern composers are trying to question in their scores. But occasionally in the modernist repertoire one comes across a piece that is both totally weird and wildly entertaining. Luckily for us, one such piece is currently enjoying its 100th anniversary year. No, I’m not talking about Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring (though it might qualify as well). I’m talking about Arnold Schoenberg’s bizarre and beautiful melodrama, Pierrot Lunaire.

Finished in the summer of 1912 and premiered throughout Europe over the following year, Pierrot transfixed some and, of course, irritated others with its lurid portrait of a commedia dell’arte clown made mad by the moon. Schoenberg drew his text for the three-part, 21-song cycle from German translations of poems by the French poet Albert Giraud. Instead of writing typical melodies for his soprano, he chose instead to have her execute the part in a relatively novel style he called Sprechstimme, or speech-singing. The effect is striking: While the singer’s lines comprise definite pitches, she approaches and leaves them in swoops and growls, producing a highly theatrical, speech-like style that sounds something like Mrs. Bucket in Keeping Up Appearances. Accompanying all this is a small-yet-agile quintet of piano, flute (with piccolo), clarinet (with bass clarinet), violin (with viola) and cello—a particular grouping which came to be called, naturally, “a Pierrot ensemble”—that surrounds the performer in a crackling cloud of atonal expressionist gestures.

If this still doesn’t sound like your thing (it is in German, after all), let me elaborate on its theatricality. Pierrot has a great deal in common with the Weimar-era cabaret that would grow in prominence in the years after WWI, and a good singer—whether or not you understand her words—will make the role feel like something worthy of an über-hip nightclub. At a stunning anniversary performance of the piece last night in New York, the Da Capo Chamber Players brought in soprano Lucy Shelton to sing-speak Pierrot, and she killed it. From the moment she approached the edge of the stage to place, with much pomp and circumstance, a small doll of the famous clown into a little wicker rocking chair, I could tell Shelton understood the sly, giddy, and even humorous impulse at the heart of the piece. That understanding carried through the entire cycle in both Shelton’s vocals and embodiment of Pierrot, which had her variously gazing wistfully at a hidden moon in the rafters, leaning on the piano with a kind of self-satisfied swagger, and gesticulating angrily at the audience and musicians over some slight that only Lady Gaga could understand.

As thrilling as Shelton’s performance was, the real treat of the evening was realizing that I had sat through 40 minutes or so of reputedly “difficult” Schoenbergian atonality and had never once experienced it as such. All the parts just made sense together. Who would have guessed that the best gateway drug to modernist music might come from the floppy pocket of an insane French clown?