The Strange, Beautiful Music That Won the Pulitzer This Year

Courtesy of Caroline Shaw.

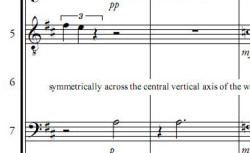

In standard classical sheet music, composers use a set of old-school Italian words to provide musical instructions that can’t be represented in notes and clefs—phrases like subito piano for “suddenly soft” and con brio ma non troppo for “with spirit but not too much.” In her vocal piece Partita for 8 Voices, composer Caroline Shaw eschews such stuffiness for a more millennial-friendly dialect. Indications like “mixy,” “floaty head voices,” and “plainchantish improv on these two pitches” loosely guide the singers through the score-thingy. But before you dismiss Shaw’s notational innovations as youthful affectation (she’s only 30), have a listen to the music they produce. The Pulitzer Prize committee did, and, earlier this week, they awarded Partita one of composition’s highest honors.

They say that a young artist should master the idioms of the past before discarding them for whatever’s next. Despite the unconventional markings, Shaw has clearly done this. She raids the vocal traditions of different eras and cultures in order to assemble something fresh and yet familiar, but only just. The admixture of medieval-ish plainchant, African-like annunciation, faux-electronic timbres and spoken word—to pick out just a few of the shinier bits in this sonic collage—didn’t exactly challenge me intellectually (as much “new music” strives to do), but it never lost my attention.

The suite opens with an allemande, an old musical form originally tied to courtly dance. (The subsequent three movements—a sarabande, courante, and passacaglia—continue this pattern.) And it provides the first taste of Shaw’s inspiration for the piece: the geometrical instruction-based art of Sol LeWitt. The singers begin by speaking and then layering phrases like “to the side” and “through the middle and” while also counting dance beats (“5, 6, 7, 8”), erupting into lively, Appalachian-tinged singing only after the spoken lines have reached maximum saturation. LeWitt’s instructions return in a more explicit form in the final movement, where longer segments from the Wall Drawings are quoted. In the meantime, we hear the thick, crunchy, punchy chord-flashes that Shaw favors in the sarabande, punctuated by a vocal sound akin to a slowed-down udu drum. And in the best movement, the courante, Shaw creates a 9-minute evocation of angel sex, complete with strained, breathy “ohs” and “ahs,” a gorgeously orgasmic hymn section followed by a quick coda containing sighs of satisfaction.

This is a deceptive sort of music, with an elegant, easy smoothness built from distinct and fascinating bits-and-pieces. Listening to it is a little like examining a great mosaic, both from a distance and occasionally with a magnifying glass, the better to see the grout between the tiles. Perhaps coincidentally, one of Shaw’s idiosyncratic style guidelines is “silk shoes gliding over marble mosaic.” She’s trying to tell her musicians how to sound, but she might as well have been telling us how to listen—no description could be more apt.