Just over a year ago, I wrote a post for this blog headlined “When Dickens Met Dostoevsky (Maybe).” The headline was a bit cute, perhaps; as I noted in the post, the supposed meeting was highly disputed—though not, at that point, definitively refuted—by scholars, and the essay which prompted the blog post, Christopher Hitchens’ last for Vanity Fair, was itself skeptical of the encounter. Still, it was a terrific story, one that had been recounted in two recent Dickens biographies as well as multiple essays and reviews. It seemed worth passing along, with appropriate caveats.

The two literary legends were supposed to have met in 1862 in the London office of Dickens’ magazine All the Year Round. According to a 2002 article in The Dickensian titled “Dickens’s Villains: Confession and a Suggestion,” Dostoevsky described the meeting in an 1878 letter to his doctor and friend S.D. Yanovksy, a letter that was supposedly published in Vedomosti Akademii Nauk Kazakhskoi SSR (Bulletin of the Kazakh SSR Academy of Sciences) in 1987. This remarkable find was brought to the Dickensian and thus the world by an obscure independent scholar with the very ordinary name of Stephanie Harvey.

Who is Stephanie Harvey? Now that is a really good story, it turns out, one that has just been told at considerable length in the Times Literary Supplement. In a 10,000-word essay, Eric Naiman, author of the 2010 book Nabokov, Perversely, tracks down the real Ms. Harvey—or, rather (spoiler alert), Mr. Harvey, a contributor to the TLS, and a genuine independent scholar, one with a much longer publication history than the fictional Stephanie, who appears to have just two published pieces to her name. A.D. Harvey, on the other hand, “is the author of nearly 10 monographs dealing with English history, literature, and culture, with a sideline in the history of military technology,” and the “author of hundreds of articles in scholarly and popular journals.”

He is also an inveterate hoaxster, as Naiman discovered, who has created numerous fictional writers, united primarily by the considerable esteem in which they hold the work of one A.D. Harvey. These pretend scholars and novelists include Graham Headley, Trevor McGovern, John Schellenberger, Leo Bellingham, Michael Lindsay, and the Italian Ludovico Parra, as well as the aforementioned Stephanie. Many of them have enviable publications on their wholly imaginary CV’s—though they also have some rather unenviable ones: Harvey has published erotica of dubious merit under both his own name and McGovern’s, and that erotica shares certain qualities with the fiction of Leo Bellingham, whose story “In for the Kill” speaks of “delightful memories of pointy little titties and spread thighs” as well as “an adorable little bum, each succulent buttock … as rounded and brown as farmhouse eggs.”

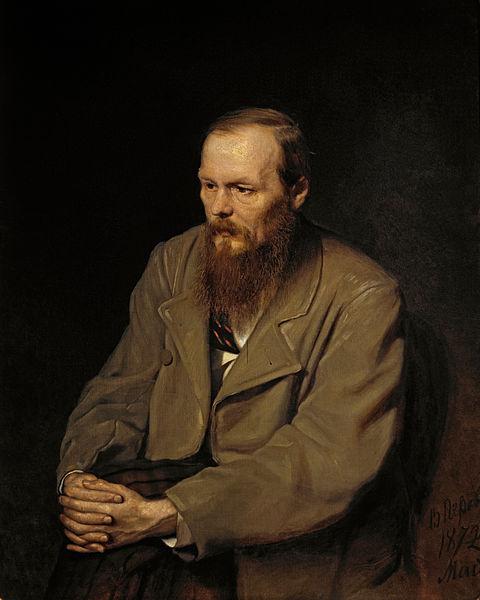

Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Vasily Perov/Wikipedia.

Of course, those passages do not come from a published piece of fiction; rather they are quoted in an academic article by one Stephanie Harvey, an article that compares Bellingham’s work, favorably, with that of Doris Lessing. But Bellingham (or, rather, A.D. Harvey as Bellingham) did publish an honest-to-goodness novel, called Oxford: The Novel, which, in 1981, was actually reviewed in… the Times Literary Supplement.

Confused? Me too, a little. I can only refer you to Naiman’s full essay for illumination. Print it out and read it when you can find a few spare minutes. It’s filled with so many remarkable details. There’s the bit about how, when the editor of The Dickensian attempted to contact Stephanie Harvey and ask about the now disputed Dickens-Dostoevsky story, he “received an email from her sister informing him that Stephanie Harvey had been severely injured in a car accident, had suffered brain damage, and only intermittently recognized members of her family.” There are the various footnotes in the collected works of these fictional personae attesting to the brilliance of A.D. Harvey’s scholarship—and even one decidedly mixed review that, we now know, Harvey gave himself. Most amazingly, perhaps, there are the little hints that one can now see in these writings, the veiled disclosures Harvey seems to have made about what was actually going on. The most delightful of these seeming clues is in the fake Dostoevsky letter that triggered Naiman’s investigation in the first place.

I don’t want to spoil that last little twist of the knife, since Naiman ends his extensively researched and reported essay with precisely that detail. Just go read his whole essay for yourself.