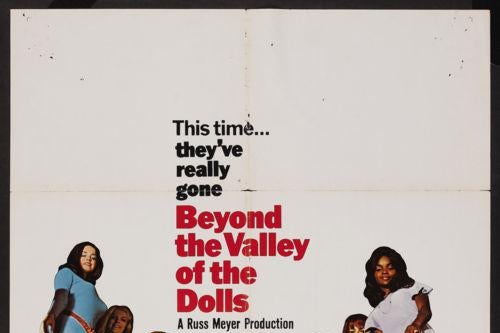

In the wake of Roger Ebert’s death, most will remember him for his work as a critic, but a small niche of fans will fete him for a more obscure but nonetheless worthy reason: his writing of the screenplay for the 1970 cult classic, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.

The madcap, sexy, borderline-surrealist film is impossible to summarize, but calling it a fast-and-loose Hollywood fantasia on A Midsummer Night’s Dream would not be totally inaccurate. A group of somewhat innocent youths—three girls in a rock band, plus one boyfriend—head into the enchanted forest of Los Angeles and there meet all manner of fairy-like creatures (rock producer Z-Man, porn star Ashley St. Ives, and other fans of “happenings”) who lead them astray. The whole thing ends, after a Hamlet-like massacre, in a very Shakespearean triple-wedding. But the plot details don’t really matter: In the final analysis, BVD is a film of unbridled sensual pleasure, a cinematic shag carpet woven with delightful details and an intoxicating frenetic energy. It is, in a word, camp.

In my ongoing Slate series on camp, I distinguish between “campy”—a style consisting of exaggeration or artificiality—and “camp,” which I define as the inexplicable pleasure of the nuance. BVD is one of those rare films blessed with a fair portion of both. It is awash in the now automatically campy colors and textures of the 1970s and delightfully mod dialog (wonderfully grating against Z-Man’s Elizabethan diction). Harpsichord-heavy scoring only adds to the aura. Mix into that such scenes as when the spurned boyfriend of one of the rocker girls falls like a sack of potatoes from the rafters to the concrete floor of the television studio in which the group is having their first televised concert—don’t worry, he’s only paralyzed, and temporarily at that—and you’ve got a campy brew going at a rolling boil.

But camp—the pleasure taken in the stray nuance—also abounds. Certain lines, like Ashley St. Ives’ orgasm-induced screaming of “nothing like a Rolls!”, captivate my personal camp attention, as do weird details like the absurdly thick glasses of the abortion doctor and the weird knot in a wood post that is used to (barely) obscure a ridiculous pastoral sex scene. I suspect Ebert would approve of such detail-oriented viewing of BVD. He admitted to writing the screenplay in only six weeks, noting that he and co-writer Russ Meyer made up the plot as they went along. But that wasn’t because they were lazy or pressed for time; it was by design. According to Ebert, BVD was “an anthology of stock situations, characters, dialogue, clichés and stereotypes, set to music and manipulated to work as exposition and satire at the same time; it’s cause and effect, a wind-up machine to generate emotions, pure movie without message.”

In other words, BVD was a purely aesthetic work, a patchwork quilt of details and nuances sewn with thread of campy outrageousness. For that, it truly is a camp classic, and worthy of celebration along with Ebert’s masterful reviews.