Lifetime is scheduled to air the TV movie Romeo Killer: The Christopher Porco Story Saturday night. Or maybe not. New York Supreme Court Judge Robert Muller issued an astounding order yesterday to stop the film from airing, and even barring Lifetime from running ads or sending out publicity for it. This is not an order that should hold up. It gets utterly wrong the balance between free speech protections and the right of an individual to control what are called “publicity rights,” the permission to use one’s name or likeness for commercial purposes.

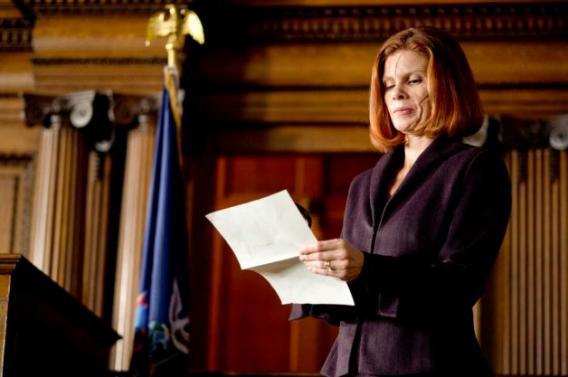

Chistopher Porco was convicted in 2004 in Albany, N.Y., for killing his father, Peter Porco, with an axe and maiming his mother, Joan Porco. Ironically, given Muller’s injunction, cameras were allowed in the courtroom and the reading of the verdict was videotaped. Also feeding interest in the case was the appearance of Joan Porco, who was badly scarred by the maiming but came to court with her son and claimed he was innocent throughout the trial. The case has already been the subject of a one-hour documentary on 48 Hours Mystery and an episode of the TruTv series Forensic Files.

Christopher Porco sued Lifetime under New York civil rights law, arguing—without having seen the film—that the movie is “fictionalized” and uses his name for “purposes of trade.” Judge Muller should have realized that the First Amendment trumps publicity rights here. Courts almost never stop movies—or books or articles or blog posts—from being published. Nor should they: As the Supreme Court has repeatedly said, the value of a big teeming marketplace of free speech and ideas outweighs the cost of publishing information that’s far more private and controversial than the facts of Christopher Porco’s history and crimes. State laws that allow people to sue when their names or likenesses are used to make money weren’t written to prevent news organizations or filmmakers from telling a story: They’re designed to stop a company from cashing in on someone’s fame to market a product without paying him—for example, the toy company that sold Arnold Schwarzenegger bobble-head dolls without getting his permission or giving him a cut. And the correct legal remedy is to give the person who wins such a suit damages, not to block a movie from making it to the screen (or even a doll from going on the shelf).

There’s some gray area in how far we get to control our own likenesses. But it in no way covers Porco’s complaint against Lifetime. In its appeal, Lifetime says that the New York Court of Appeals, the high court in the state, has “time and again” said that this part of the state civil rights law doesn’t apply to “newsworthy information,” broadly defined. That has to be the right answer. If you have this movie queued up for Saturday, you should be able to watch it as planned. In fact, maybe this lawsuit will end up doing Lifetime a big favor—think of all the free publicity.

Update, March 21, 4:51 p.m.: An appeals judge has issued a stay of the prior restraint against Lifetime, allowing the network to air the movie as scheduled.