Randy Moore’s dark drama Escape From Tomorrow premiered this week at the Sundance Film Festival and quickly became one of the most buzzed-about oddities in Park City, Utah. Reviews have been mixed but unquestionably intriguing. There’s a chance, though, that the rest of us won’t be able to form our own opinions: Escape From Tomorrow was filmed without permission on location at Disney’s theme parks in Orlando, Fla., and Anaheim, Calif., and it unabashedly incorporates the familiar logos, characters, and theme-park images in a perverse dramatic narrative. So will Disney prevent the movie from ever reaching theaters?

First, a little background: Moore and a small group of actors and crew went undercover as tourists for just under a month in order to film the movie. Scripts and all shooting directions were kept on their iPhones so that “when actors and crew were looking down between takes, passersby just thought they were glancing at their messages.” The actors wore the same clothes every day, but park employees seemed unsuspecting—perhaps, Moore has noted, because there are so many people who come and go through the park every day, taking pictures and recording home movies constantly. The kind of camera Moore’s crew used, a Canon 5D DSLR camera, while pricey, is small and inconspicuous. Smart phones and hidden digital recorders placed on the actors’ bodies recorded the sound.

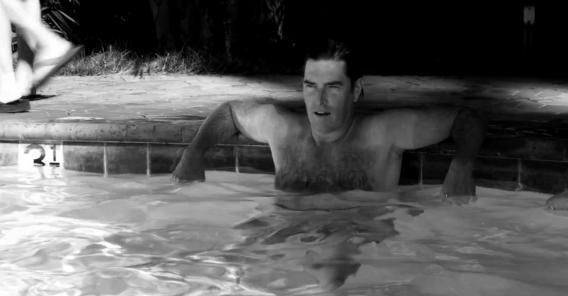

Disney has yet to make any official statements about the film, but it’s easy to see why they might get in the way. It’s about a day in the life—and fantasies—of a father (Roy Abramsohn) vacationing with his family at Disney World. Some Disney princesses turn out to be undercover hookers for Asian businessmen; Epcot Center is apparently blown up. A clip from the film, in which Abramsohn gazes at two young French girls in a pool, hints at the film’s less-than-family-friendly quality.

So Disney may very well want to keep this movie away from theaters. But will it succeed?

Maybe. Like the documentary film Exit Through the Gift Shop—which also featured unauthorized footage of Disneyland and which was never opposed by Disney—Escape From Tomorrow arguably falls under the “fair use” protection, a copyright exception “based on the belief that the public is entitled to freely use portions of copyrighted materials for purposes of commentary and criticism.” Moore himself has described his film as precisely that sort of commentary: “I think Walt Disney was a genius,” he has said. “I just wish his vision hadn’t grown into something quite so corporate.” As Tim Wu points out in The New Yorker, “There is no real chance that anyone would plausibly think that the film was sponsored by or affiliated with Disney.”

But even if a reasonable interpretation of fair use would grant Moore permission to use those trademarked images, the director is not necessarily in the clear. For one thing, Disney has rules about behavior in its parks, and it’s possible Moore violated these and could be subject to penalties on those grounds. (An email to Disney inquiring about their theme park terms of use and privacy laws was not returned.) There’s also the matter of passersby in the park—which is not a public space—being filmed without their consent. While the law on that issue is not black and white either, those people could file suit—and those suits could have criminal repercussions if the film were commercially released, particularly if Moore filmed children without getting the consent of their parents.

Moore seems to know how much he was risking: He swapped out the audio of Disney songs played during certain attractions, knowing he wouldn’t get the rights to them. And he has admitted that he’s nervous about Disney’s potential reaction. He has reason to be. Even if Disney doesn’t make a move right away, the boldness of his film will likely make it difficult for him to sell Escape From Tomorrow to distributors. Taking on Disney—which is notoriously strict on its copyright laws—leaves him open to potentially hefty lawsuits. Though as Disney well knows, even if you try to make a film go away completely, those who really wish to find it probably will.

Slate thanks Julie Ahrens of Stanford University and New York film and entertainment lawyer John J. Tormey III, Esq.