In 1963, Duke Ellington directed and narrated My People, a song-and-dance revue he wrote about African-American history, which was presented in Chicago as part of the Century of Negro Progress Exposition. The album finally became available once again this past September, 20 years after its last re-release. (The new version also has 15 more tracks than previous releases.)

The revue’s most striking song is a stunning tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “King Fit the Battle of Alabam.” Ellington, outraged by the actions of Bull Connor and the police in Birmingham, Ala., in April 1963, re-imagined King as the protagonist of “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho,” writing a powerful, forward-looking salute not only to King but to Birmingham’s courageous black residents as well. In Ellington’s song, one of Connor’s dogs pulls “his Uncle Bull’s coat,” and says, “That baby acts like he don’t give a damn. Are you sure we’re still in Alabam?”

Today, it’s surprising to hear Ellington connect King to Joshua: Thanks to the metaphor of the mountaintop in the haunting speech he gave on April 3, 1968, the night before his assassination, King is forever associated with Moses. Joshua is from the generation after (hence the title of David Remnick’s 2008 piece on Barack Obama, “The Joshua Generation”). Perhaps Ellington associated those in the generation of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman with Moses.

“King Fit the Battle of Alabam” is not widely known, but deserves an honored place among the many musical tributes to Dr. King by Big Maybelle, Nina Simone, and others. In his autobiography, Music is My Mistress, Ellington claims it is “the first published song that sang [King’s] praises.” And King himself heard it rehearsed, appreciating it so much that he, allegedly, wept—an anecdote recounted in Harvey G. Cohen’s magnificent 2011 cultural biography Duke Ellington’s America, which has a comprehensive chapter on My People. According to Cohen, Ellington sang the lyrics himself when he performed it in the summer of 1963. And though Ellington was known for his witty monologues and banter, he did not typically sing on his recordings.

My People contains a second tribute to King, a hard-swinging up-tempo number simply titled “King,” which was not included in previous releases of the revue. “King” is vintage Ellington swing, with an energy and intensity to match King’s own tireless efforts. Thus, not only did Ellington honor King with a topical, politicized re-working of a Negro spiritual, but also with a fine example of the type of composition for which he was best known.

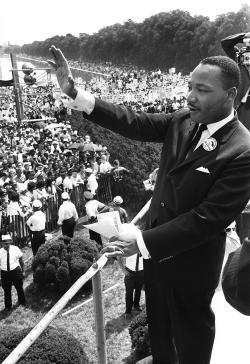

The composition of My People was a personal labor or love for Ellington. Though he often collaborated with Billy Strayhorn on his other work, he took full credit for My People, saying in Music Is My Mistress that he “wrote the words, music, and orchestrations … directed it, and did everything but watch the loot.” My People ran at the Century of Negro Progress from Aug. 16 until Sept. 2, 1963, and the recording took place on some of those dates in between—including Aug. 28, 1963, the day of the March on Washington.

Though Ellington was filled with deep admiration for King, he was skeptical of the march. In a “private” 1964 interview quoted by Cohen, Ellington said the march resulted mainly in the enrichment of hotel and restaurant owners, while creating a grand spectacle that would be difficult ever to repeat. If, on the other hand, every black person in the U.S. contributed one day’s pay, he said, $100 million could be raised for a more concerted lobbying effort—one that he would be willing to coordinate personally. Ellington took flack throughout his career for occasionally appearing aloof on the matter of civil rights.

But the jazz critic Stanley Dance, a close confidant of Ellington, read the following at Ellington’s funeral in 1974, and it rings true today:

Categories of class, race, color, creed and money were obnoxious to him. He made his subtle, telling contributions to the civil rights struggle in musical statements—in “Jump for Joy” in 1941, in “The Deep South Suite” in 1946, and in My People in 1963. Long before black was officially beautiful—in 1928, to be precise—he had written “Black Beauty” and dedicated it to a great artist, Florence Mills. And with “Black, Brown and Beige” in 1943, he proudly delineated the black contribution to American history.