Last week the National Board of Review chose the fun but forgettable Wreck-It Ralph as the year’s best animated film, and the New York Film Critics Circle Awards chose Tim Burton’s gorgeously rendered Frankenweenie. Over the weekend, Boston and Los Angeles also went for Frankenweenie, and between now and Oscar time, we may see some love for Studio Ghibli’s The Secret World of Arrietty, Laika’s ParaNorman, and Brave, the latest but not greatest from Pixar.

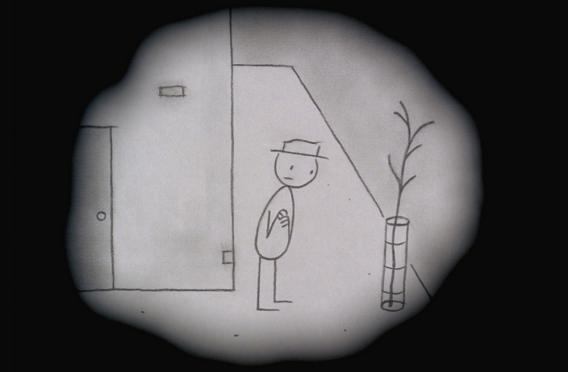

But the best animated film of the year is about a stick figure named Bill. Bill is the star of It’s Such a Beautiful Day, the latest from independent animator Don Hertzfeldt. Hertzfeldt is known for making sick, hilarious shorts films about endless dental procedures and balloons that turn on toddlers. As those descriptions suggest, his earlier shorts, which might be described as Looney Tunes directed by Franz Kafka, aren’t for everyone. Ironically, this was more or less the point of his 2000 short Rejected, and yet it still won over enough members of the Academy to get nominated for an Oscar.

But from the opening moments of It’s Such a Beautiful Day, which is a feature Hertzfeldt completed in the three parts over the course of five years, it’s clear that Hertzfeldt is after something different. The movie’s first image is not animated but live-action, and the opening notes of the soundtrack are the opening harp strings and flutes of The Moldau, a symphonic poem you might recognize from Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life. This isn’t the last time the movie will use live-action footage or grand symphonic works: Another one of the movie’s recurring motifs is the Vorspiel, from Wagner’s Das Rheingold, which happens to be another favorite of Malick’s. These musical cues may be partly tongue-in-cheek—Hertzfeldt hasn’t lost his sense of the absurd—but they also suggest the grandeur of Hertzfeldt’s ambitions.

Bill’s only distinguishing visual feature is his top hat—this is how you can tell him from the other stick figures—but you won’t soon forget him. Most of It’s Such a Beautiful Day takes place in Bill’s mind, as it slowly falls apart. What exactly is happening to Bill? For most of the movie we’re as confused about that as he is. Bill imagines a monstrous fish head feeding on his skull, and soon the guy at the bus stop next to him has the head of a cow. But the effect is a harrowing and darkly comic portrait of the unraveling of a mind, whether through psychosis, or, as others will relate to it, senile dementia: As the story winds down, every last moment of Bill’s life, both mundane and magical, slips away from him, and it becomes not unlike the ticking down of our own lives. In the end—and I can say this without spoiling anything—it’s a stick-figure memento mori.

And though the animation, sound, and special effects were all done by one man slaving away at his home, It’s Such a Beautiful Day is realized with remarkable inventiveness and technical sophistication. In addition to its sequences of pen-and-paper animation, Bill’s daydreams and hallucinations send the film into flights of Douglas Trumbull-style special effects reminiscent of 2001 (or, again, The Tree of Life). And as with so many of Hertzfeldt’s movies, if you see it somewhere other than on your laptop, you might be struck by its sound design: Hertzfeldt likes to complement the mostly blank pages of his visuals with lush, atmospheric sound that is almost their exact opposite. In It’s Such a Beautiful Day he makes use of sounds sped-up, slowed-down, played backwards, and panned from channel to channel, arriving at a surreal soundscape akin to what David Lynch achieved in Eraserhead.

Other than festival appearances and Hertzfeldt’s in-person theatrical tour, It’s Such a Beautiful Day was only given a brief, limited theatrical release. (It did not qualify for the Oscars.) But you can watch the first chapter of It’s Such a Beautiful Day above, and you can buy the DVD on Hertzfeldt’s website. The first chapter doesn’t convey the full scope of the movie—it gets more and more sophisticated as it goes along—but don’t be surprised if, just in these first few minutes, you start to really care about that stick figure