Steven Spielberg’s new historical drama Lincoln, written by Tony Kushner and based in part on Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals, depicts the crucial final weeks of Abraham Lincoln’s life, when he helped push the 13th Amendment through Congress and bring an end to the Civil War.

How honest is this portrait of Honest Abe? Below is a handy guide to help you sort the fact from the fiction. There are some spoilers ahead, so if you’d like to go into the movie not knowing what Mrs. Lincoln thought of Our American Cousin, come back after you’ve seen the movie.

Lincoln’s dream

Lincoln often spoke of a mysterious recurring dream about a ship, just as in the movie. However, Lincoln usually interpreted the dream as being not about the 13th amendment, but instead as being an omen of military victory. Lincoln’s secretary of the navy, Gideon Welles, wrote about one time that Lincoln told him about his dream, while they were awaiting an update from General William Tecumseh Sherman:

The President remarked it would, he had no doubt, come soon, and come favorable, for he had last night the usual dream which he had preceding nearly every great and important event of the War. Generally the news had been favorable which succeeded this dream, and the dream itself was always the same. … He said it related to [my] element, the water; that he seemed to be in some singular, indescribable vessel, and that he was moving with great rapidity towards an indefinite shore; that he had this dream preceding Sumter, Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg, Stone River, Vicksburg, Wilmington, etc.

According to White House guard William Henry Crook, Lincoln also spoke of having the dream the night before he was assassinated.

Lincoln’s stories

Just as in Lincoln, Uncle Abe was renowned for his love of storytelling, and his talent for it. Here’s one description from Team of Rivals:

In these convivial settings, Lincoln was invariably the center of attention. No one could equal his never-ending stream of stories nor his ability to reproduce them with such contagious mirth. As his winding tales became more famous, crowds of villagers awaited his arrival at every stop for the chance to hear a master storyteller.

One of the most memorable anecdotes delivered by Lincoln in the film is the story of Ethan Allen’s visit to England. Whether the content of Lincoln’s story is true or not, it was, according to Team of Rivals, one of his favorites:

One of Lincoln’s favorite anecdotes sprang from the early days just after the Revolution. Shortly after the peace was signed, the story began, the Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen “had occasion to visit England,” where he was subject to considerable teasing banter. The British would make “fun of the Americans and General Washington in particular and one day they got a picture of General Washington” and displayed it prominently in the outhouse so Mr. Allen could not miss it. When he made no mention of it, they finally asked him if he had seen the Washington picture. Mr. Allen said, “He thought that it was a very appropriate [place] for an Englishman to Keep it. Why they asked, for said Mr. Allen there is Nothing that Will Make and Englishman Shit So quick as the Sight of Genl Washington.”

Another story Lincoln recounts is the tale of 70-year-old Illinois woman Melissa Goings, who allegedly murdered her husband. Lincoln suggests he aided in Goings’ escape from the law. This story, too, is taken almost verbatim from historical accounts:

Testimony indicated he was choking her and she broke loose, got a stick of stove wood, and fractured his skull. The dead man had a name for quarreling and hard drinking and his last words were, “I expect she has killed me. If I get over it I will have revenge.” … Public feeling ran overwhelmingly in her favor. Indications were that Lincoln held a conference with the prosecuting attorney, and that on the day set for trial Mrs. Goings was granted time for a short conference with her lawyer, Mr. Lincoln [and] was never again seen … A court bailiff, Robert T. Cassell, later said that when he couldn’t produce the defendant for trial he accused Lincoln of “running her off.” Lincoln replied, “Oh no, Bob. I did not run her off. She wanted to know where she could get a good drink of water, and I told her there was mighty good water in Tennessee.

As for his speeches, he really did—at least at some points in his career—keep scraps of paper in his hat.

Lincoln’s voice

Lincoln’s surprisingly high-pitched voice and accent sound “uncanny, convincing, and historically right” according to Lincoln historian Harold Holzer. (More: Does Daniel Day-Lewis Sound Like Lincoln?)

Mary Todd Lincoln

Toward the end of Lincoln, Mary Todd Lincoln (Sally Field) predicts that “All everyone will remember of me was that I was crazy and that I ruined your happiness.” This is partially true, though in recent years some have disputed the idea that the First Lady really suffered from mental illness. Today many historians believe that she was a whip-smart, politically savvy woman. (More: Was Mary Todd Lincoln Really Insane?)

Lincoln’s sexuality

There is little evidence that Lincoln was gay. The movie, perhaps accordingly, offers little more than a suggestion. (More: How Gay Is Lincoln?)

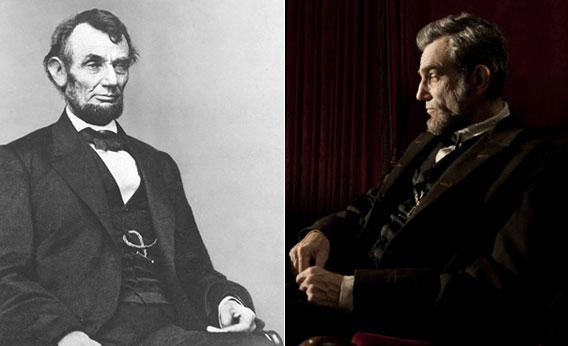

Beards and appearances

Lincoln’s casting, makeup, and costume departments achieved strong resemblances between the actors in the film and the historical figures they represented. We’ve assembled a gallery where you can compare the actors and the historical figures side-by-side.

Lincoln’s pardons

The pardons Old Abe signs in Lincoln are based on the real pardons that he gave many deserters, preferring that they “fight instead of being shot.” For an extraordinary example of one such pardon, head to “Abraham Lincoln Scrawled This Astonishing Note to Save a Union Soldier’s Life.”

The peace talks

As in Lincoln, the vote on the 13th Amendment took place just as Confederate representatives were headed north for peace negotiations. When word of these peace commissioners got out, there was a motion to delay the vote until after negotiations, which could have put the vote in jeopardy. However, Lincoln was able to defuse this rumor by using carefully worded language, just as in the movie. He wrote:

To: James Ashley So far as I know, there are no peace commissioners in the city or likely to be in it. A. Lincoln

This was technically true—the commissioners were on their way to Fortress Monroe, not Washington—and also a bit disingenuous. Lincoln met with the commissioners at Fortress Monroe a few days later.

The vote

Lincoln was able to pass the 13th Amendment due in large part to the work of three men who twisted arms on his (and Secretary of State William Seward’s) behalf. While it’s not well documented how these men procured the necessary votes and abstentions of lame duck Democrats, it does seem possible that they could have promised patronage positions in return, as they do in the film.

On the day of the vote, the proceedings played out much as they do in the movie, but Spielberg does take a few dramatic liberties. While free blacks were allowed in the galleries and some number of them (including one of Frederick Douglass’ sons) did come out for the vote, historians don’t think that they came out in quite the extraordinary force that they seem to in the movie. There may, however, have been an unusual number of women, who had been instrumental in the abolitionist movement.

The vote itself plays out much as it would have in real life. George Yeaman (Michael Stuhlbarg) of Kentucky, a slave state, really did change his position on the amendment in order to vote yes. And at the end of the vote, the speaker, Schuyler Colfax, really did break tradition in order to cast a vote. However, it’s very unlikely that Thaddeus Stevens was able to sneak the document home for the night once it was over.

The politicians involved in the vote would most likely not have called it “the 13th Amendment.” They would have called it, for example, “the Constitutional amendment,” or “the Constitutional amendment abolishing slavery.”

Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens’ support for black suffrage, which provides one of Lincoln’s central conflicts, really was one of his most radical and controversial stances. In 1865, the Republican Congressman argued that “Without the right of suffrage in the late slave States (I do not speak of the free States,) I believe the slaves had far better been left in bondage.” However, in the deliberations before the amendment was passed, he was forced to reassure wavering Democrats that the amendment would not guarantee the equality of black people, in order to pass the amendment. He told them it pertained only to equality before the law.*

One of the other standout features of Tommy Lee Jones’ Thaddeus Stevens is his virtuosic talent for putdowns. While many of these seem to be inventions of screenwriter Tony Kushner’s, his razor-sharp tongue was inspired by history: For example, he once attacked Masons as a “feeble band of lowly reptiles”—an insult similar to one Stevens uses in the film to describe his rival Democrats.

Perhaps the film’s biggest surprise comes when Stevens gets in bed with his mulatto housekeeper (S. Epatha Merkerson) and apparent lover. Some have speculated that Stevens’ housekeeper, Lydia Hamilton Smith, really was his mistress. Stevens was accused of this by his anti-abolitionist critics, though there’s no concrete evidence it was true.

Robert Todd Lincoln

Mary Todd Lincoln really did insist that Robert Todd Lincoln stay in college rather than enlisting in the army. The First Lady had already lost two sons, Edward “Eddie” Lincoln and William “Willie” Lincoln, and didn’t want to lose another. In January 1865, when the movie takes place, Lincoln wrote Ulysses S. Grant and asked if Robert could be placed in Grant’s “military family with some nominal rank.” Grant agreed to have him.

After joining up, Robert Todd Lincoln really was present for the surrender of General Robert E. Lee at the Appomattox Court House, where he waited on the front porch. However, the surrender may not have been as dramatic as depicted in the film: As Robert Lincoln told a newspaper reporter in 1881, “As I recall the scene now, it appeared to be a very ordinary transaction. … It seemed just as if I had sold you a house and we had but to pass the titles and other conveyances.” He would live to become the last living witness of the surrender.

The assassination

In a subversion of our expectations (and perhaps a gesture of respect), Lincoln doesn’t show Abraham Lincoln’s assassination at Ford’s Theatre. Instead, Spielberg takes us to Grover’s Theatre, where Tad had gone with his tutor to see Aladdin. The twelve-year-old learned of his father’s death when a theater manager interrupted the play’s action to announce that the president had been shot.

Thanks to Michael Vorenberg, author of Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment, and Eric Foner, author of The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery.

*Correction, Nov. 9, 2012: This post originally misquoted Thaddeous Stevens as referring to “slate States” rather than “slave States.”

Previously

Presidents In Movies: The All-Time Leaderboard

Four Score and 17 Years of Lincoln in Film

How Accurate Is Argo?

How Much Scientology Made It Into The Master?