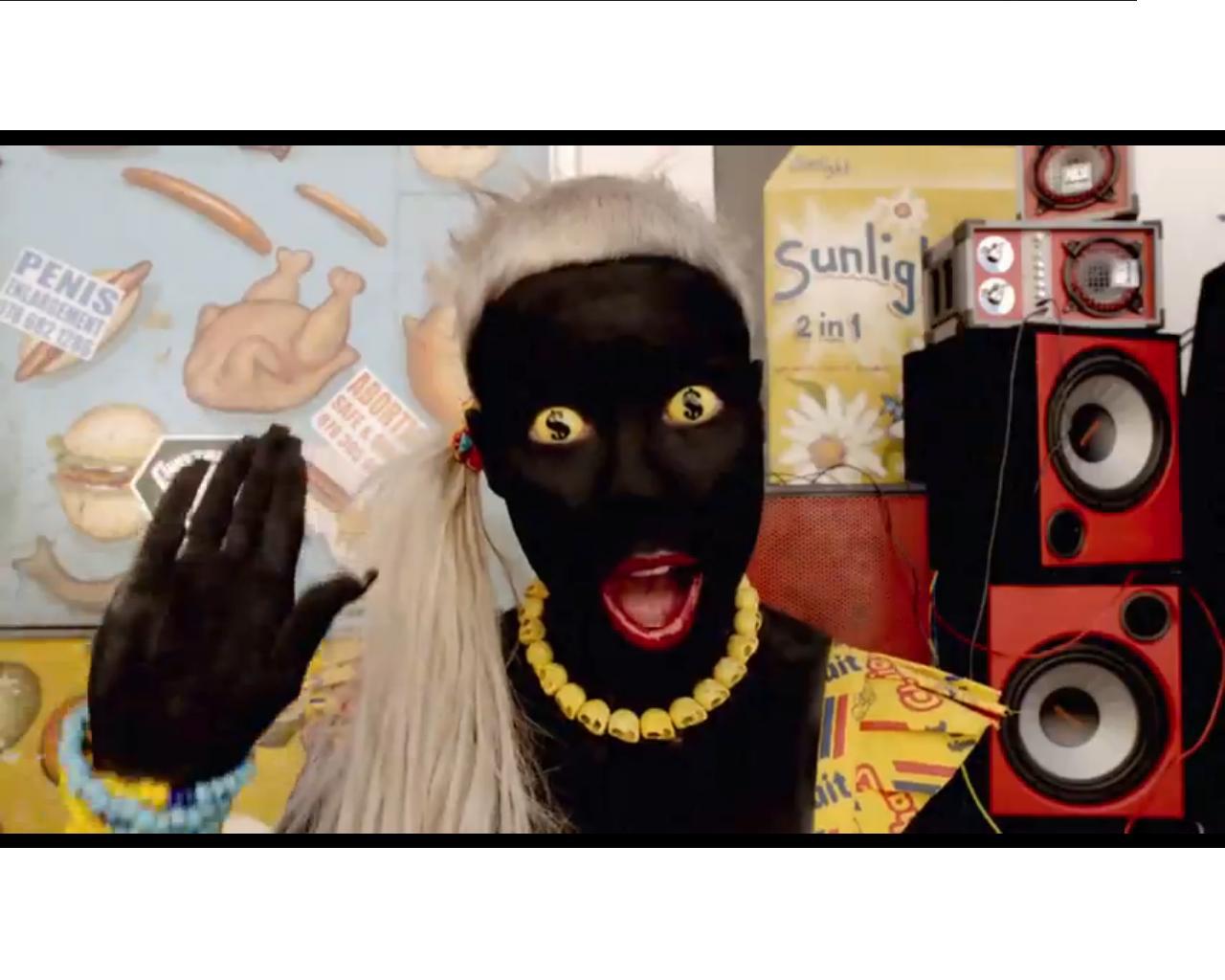

Die Antwoord (Afrikaans for “The Answer”), a South African rap-rave duo, have just released a new video for their song “Fatty Boom Boom.” Among the many batshit elements of the NSFW production is a get-up donned by one of the two that looks an awful lot like blackface. “Die Antwoord totally wear blackface in their new video,” writes Tom Breihan at Stereogum. “Awesome, right? That’s really exactly what we all needed to see today.” Breihan is attempting, I think, to convey his general puzzlement: The duo, Ninja and Yo-Landi Vi$$er, who are white, are known as provocateurs. So is this really blackface, and should we be bothered by it?

Die Antwoord (Afrikaans for “The Answer”), a South African rap-rave duo, have just released a new video for their song “Fatty Boom Boom.” Among the many batshit elements of the NSFW production is a get-up donned by one of the two that looks an awful lot like blackface. “Die Antwoord totally wear blackface in their new video,” writes Tom Breihan at Stereogum. “Awesome, right? That’s really exactly what we all needed to see today.” Breihan is attempting, I think, to convey his general puzzlement: The duo, Ninja and Yo-Landi Vi$$er, who are white, are known as provocateurs. So is this really blackface, and should we be bothered by it? Yes and yes. While the U.S. and South Africa each have quite distinct and complicated histories when it comes to race relations, blackface has been a troubling issue for both countries. The culture of blackface and minstrelsy in South Africa dates to the 1860s, when English settlers arrived. Since that time, a minstrel festival, first known as the Coon Carnival, has been held in Cape Town every year. The Kaapse Klopse, as it is now known, primarily features the working class coloured population of South Africa these days, participating in a subversive act meant to reject white superiority and the images it has thrust upon them.

Yes and yes. While the U.S. and South Africa each have quite distinct and complicated histories when it comes to race relations, blackface has been a troubling issue for both countries. The culture of blackface and minstrelsy in South Africa dates to the 1860s, when English settlers arrived. Since that time, a minstrel festival, first known as the Coon Carnival, has been held in Cape Town every year. The Kaapse Klopse, as it is now known, primarily features the working class coloured population of South Africa these days, participating in a subversive act meant to reject white superiority and the images it has thrust upon them.

Such continued use of blackface may or may not actually reclaim control of their own images, but at the very least, it attempts to wrestle with the history behind it, unlike some costumes during Halloween or misguided school pep rallys, which are clearly and obviously unacceptable. Likewise, I am reluctant to criticize an artistic use of it if there is an intelligent point to be made, as in Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, for instance. “Fatty Boom Boom” is not an example of this. Die Antwoord’s appropriation of blackface here is in line with the—some say false—persona they have carved out for themselves as rebellious, in-your-face provocateurs who are meant to bring a voice to the disenfranchised. University of Cape Town Professor Adam Haupt has called them out for a very different video, which makes extensive use of Afrikaans and coloured cultural allusions—even though Ninja himself is a “well-resourced white, English-speaking South African.”

At the beginning of “Enter The Ninja,” he declares,

Hundred percent South African culture. In this place, you get a lot of different things. Blacks, whites, coloureds. English, Afrikaans, Xhosa, Zulu, watookal [whatever]. I’m like all these different things, all these different people, fucked into one person.

This self-proclaimed spokesperson status is something Ninja has in common with Lady Gaga, who he and Yo-Landi Vi$$er are so keen to lambast in the video for “Fatty Boom Boom.” (Earlier this year, Gaga asked the group to tour with her; they said no, calling her music “shitty.”) The pop star has dubbed herself “Mother Monster” and her followers “Little Monsters,” presenting herself as the voice for many gay young people. (She herself is bisexual.) She has occasionally been criticised for pimping the cause of gay rights for her own commercial benefit. Whatever the worthiness of the cause, to present yourself as the representative and spokesperson for an entire group is a dubious endeavor.

And so Die Antwoord’s attempt to attack the singer as an opportunist is a classic case of the pot calling the kettle, well, black. In the lyrics, Die Antwoord invoke other examples of white musicians appropriating black music to great fanfare—Vanilla Ice and Eminem both get quoted—and suggest that they are the true cultural beacons: “What happened to all the cool rappers from back in the day? / Now all these rappers sound exactly the same / It’s like one big inbred fuck-fest.”

But Die Antwoord fail to bring anything fresh to the subject. Instead, they borrow loaded imagery for a cheap thrill, and do little with the horrific history behind it.