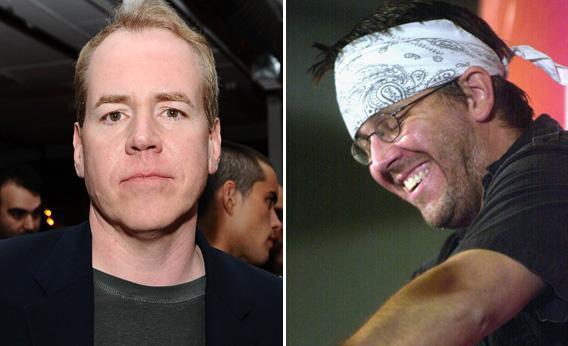

In a full-on attack launched late last night on Twitter, American Psycho author Bret Easton Ellis called David Foster Wallace “the most tedious, overrated, tortured, pretentious writer of my generation,” finally concluding that he was “a fraud.”

Ellis didn’t stop at DFW. He also sniped at his fans:

And lest the assault be called simply the kind of ill-considered rambling Twitter seems to enable, Ellis resumed firing this morning:

When he gets going like this, and he does often, it’s tempting to dismiss Ellis as only a provocateur or a troll with an unusually high brow (and profile). Indeed, he’s obsessed with a class of filter-less provocateurs that he praises as “post-Empire”—celebrities like Charlie Sheen, John Mayer, and Eminem. And Ellis has attracted controversy several times himself. In 2010 he suggested that women are inherently ill-equipped for directing movies. Just last month he declared that Matt Bomer couldn’t play the title role in a film adaptation of 50 Shades of Grey because he’s too gay. Hours after J.D. Salinger died, he tweeted, “Yeah!! Thank God he’s finally dead. I’ve been waiting for this day for-fucking-ever. Party tonight!!!”

But there’s something older than trolling going on here. In fact, this literary beef is more than two decades old, and Ellis’s weren’t the first shots fired. DFW had similarly harsh words—if less ad hominem—for Ellis all the way back in his earliest published essay, from 1988. In “Fictional Futures and the Conspicuously Young,” Wallace criticized Ellis’s subcategory of novelists (he called them the “Catatonics”) for their “naïve pretension.” Wallace’s argument, characteristically, defies easy summary, but in short he didn’t think they could turn TV and other popular entertainment into something profound “simply by inverting [their] values.” He went on:

The attitude betrayed is similar to that of lightweight neo-classicals who felt that to be non-vulgar was not just a requirement but an assurance of value, or of insecure scholars who confuse obscurity with profundity. And it’s just about as annoying.

Not quite as blunt as calling someone an insufferable fraud, but, in the context of a literary critical essay, it’s pretty close. As Salon points out, Wallace would lay into Ellis’s work again a few years later, in an interview with Larry McCaffery. American Psycho, he said, “panders shamelessly to the audience’s sadism for a while, but by the end it’s clear that the sadism’s real object is the reader herself.” His final verdict was damning:

You can defend “Psycho” as being a sort of performative digest of late-eighties social problems, but it’s no more than that.

So why is Ellis firing back now? Just last week Wallace’s thoughts on Ellis were put back into print again, in D.T. Max’s much-anticipated new biography of the late author. The book details how Wallace struggled with Ellis’s influence on his own work, refusing to acknowledge it. Wallace, in Max’s words, hoped to transcend “Ellis-type fiction,” and in his work critics ultimately found “a corrective to the literary brat pack of Bret Easton Ellis [et al.].” Much later, the biography quotes a passage from Wallace’s notebook, in which he compares Ellis’s work unfavorably with Dostoevsky’s “will to construct OWN meaning.” “Dostoevski,” Wallace wrote, “has BALLS.”

It’s no wonder then that Ellis, as he’s reading the bio, might be feeling a bit defensive. After all, he still identifies with much the same strategy that the young Wallace of the biography transcends. (In his last tweet before last night’s outburst, Ellis reaffirmed: “The rejection of middlebrow sentimentality is the most furiously important thing an artist can achieve right now in this historical moment.”) While it might be cruel to attack a contemporary who (tragically) can’t defend himself, it’s true that “Saint DFW,” as Ellis sardonically calls him, fired first.

Previously

Franzen, Wallace, and the Shame of Storytelling

Watch an Uncut 84-Minute Interview with David Foster Wallace

Were DFW’s Favorite Books Mostly Thrillers?