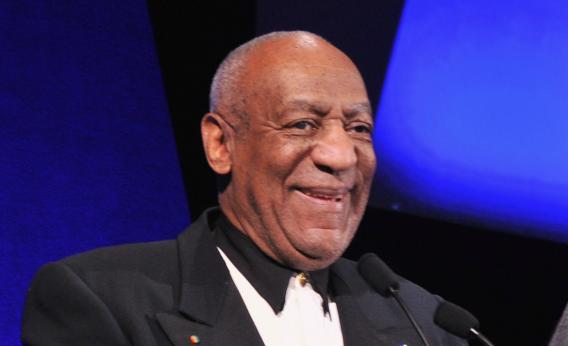

A state law that will recognize publicity rights for decades after a person’s death has recently passed the Massachusetts Senate and has moved to a House Committee, thanks to the efforts of Bill Cosby. The comedian, who lives in Shelburne Falls, Mass., wishes to protect his brand and prevent his likeness from being used after his death to promote causes and products he does not support. Cosby’s bill has been successful thus far, but it raises some tricky questions about who owns a person’s image after that person’s death, and how long such ownership lasts. Can a person’s identity, like a book or a film, ever enter into the public domain?

Yes, but only in specific circumstances. While the works a celebrity may produce—a movie, book, television show, album—are under copyright, their likeness is governed by trademark laws. Trademarks are defined as any “word, name, symbol, device, or any combination, used or intended to be used” to indicate the source of certain products. They’re meant to act as seals of approval. Both Marily Monroe’s and Michael Jackson’s signatures are trademarked, for instance. Anyone—even someone who has no personal association with the celebrity—can register for a trademark, though it is not a simple process. Once granted, the trademark remains in place for as long as its owner makes use of it. If a trademark sits dormant for more than two years, it is no longer valid, and all claims to a person’s likeness are fair game.

There are limits to what can be trademarked, however. In a case involving photographs of Babe Ruth used on a calendar without his heirs’ permission, the Second Circuit Court ruled that if a specific image of a celebrity has been consistently used on certain products, it could be considered a valid trademark. An estate does not simply hold exclusive trademark rights to every image of a celebrity, in other words. Often it comes down to whether the consumer would reasonably believe that the subject themselves, or their estate, endorsed the image’s use.

The use of holograms of long-dead celebrities raises concerns similar to the ones Cosby is trying to address. Marilyn Monroe’s estate is currently fighting a company called Digicon Media, which intends to create a hologram of the cinematic icon for a proposed concert event. The estate has threatened legal action should Digicon proceed with its plan. Should the fight go to court, the ensuing case could help establish how such post-mortem rights are handled in the celebrity-hologram era.

Another legal matter at issue in such cases is the “right of publicity,” which protects distinct personalities. Only 18 states currently recognize a post-mortem right of publicity, with time limits that vary from state to state. California law covers a person’s lifespan plus an additional 70 years; in Oklahoma, it’s an additional 100 years. New York, where Monroe’s estate has been probated (apparently in order to avoid California estate taxes), does not recognize a right of publicity after someone’s death. Nor does Cosby’s home state of Massachusetts—for now, at least.

I spoke with Lloyd Jassin, a New York-based entertainment lawyer, who says that the lack of a national right to publicity law creates a “patchwork quilt” of legal enforcement. The lack of a federal law also makes it possible for personalities to enter the public domain. Jassin says that living celebrities would be wise to trademark their names and likenesses and to assert their right to publicity. Otherwise, their identities will belong, legally and otherwise, to the rest of us.