Director Tony Scott, who killed himself yesterday, is remembered more fondly by my teenage self than by the adult I’ve become. I recall eagerly pre-ordering a copy of Top Gun to showcase my family’s then state-of-the-art DVD player. The movie soared with Scott’s signature sheen and hyperkinetic approach to editing, a style perfectly suited to putting you in the cockpit of an F-14 fighter jet.

At the movie theater—and on cable—I looked for Scott’s name, having developed a taste for his quick cuts, blue tints, and satellite zooms. If Enemy of the State was on USA, or if Crimson Tide was on TNT, you could count me in. Who cared if Days of Thunder was just a land-bound rehash of Top Gun? My brothers and I certainly didn’t. It featured fast cars and a wheelchair race down a hospital hallway. Scott provided escapist thrills perfect for fueling adolescent fantasies.

A few people have blamed Scott for ruining the movies, but he earned his infamous place in movie history by doing his job well. As Mark Harris wrote in his GQ essay “The Day the Movies Died,” the success of Top Gun ushered in an age when projects were weighed less on their merits as films than on their value as marketable products. But just as it’s hard to blame Jaws and Star Wars for the decline of Hollywood movies—they are, after all, cinematic classics—it’s also hard to blame Top Gun. It’s good! Sure, it’s not exactly Jaws, but it’s not Transformers 2, either.

Rather than borrowing the brand-name appeal of comic books or toy lines, Tony Scott created his own commercial brand. And it wasn’t just his style that was his signature. Scott’s heroes shared a thrill-seeking quality—one the avid rock-climber may have related to—and they often had complicated relationships with their friends and rivals. Look at the poster for nearly any Scott film and you’ll see the faces of two fierce competitors struggling to work together.

It’s tempting, when looking at those posters, to think of the Scott brothers, Tony and Ridley. Like many of Tony’s characters, the brothers were both friends and competitors. In the mid-1990s they started Scott Free Productions and released many films together under its name, and their movies were inevitably compared—usually in ways unfavorable to Tony. In interviews, Tony expressed a keen awareness of his less favorable status among critics and with the Academy. (He was never nominated for an Oscar.) But he seemed entirely comfortable with his approach. “Ridley makes films for posterity,” he said. “His films will be around for a long time. I think my films are more rock ’n’ roll.”

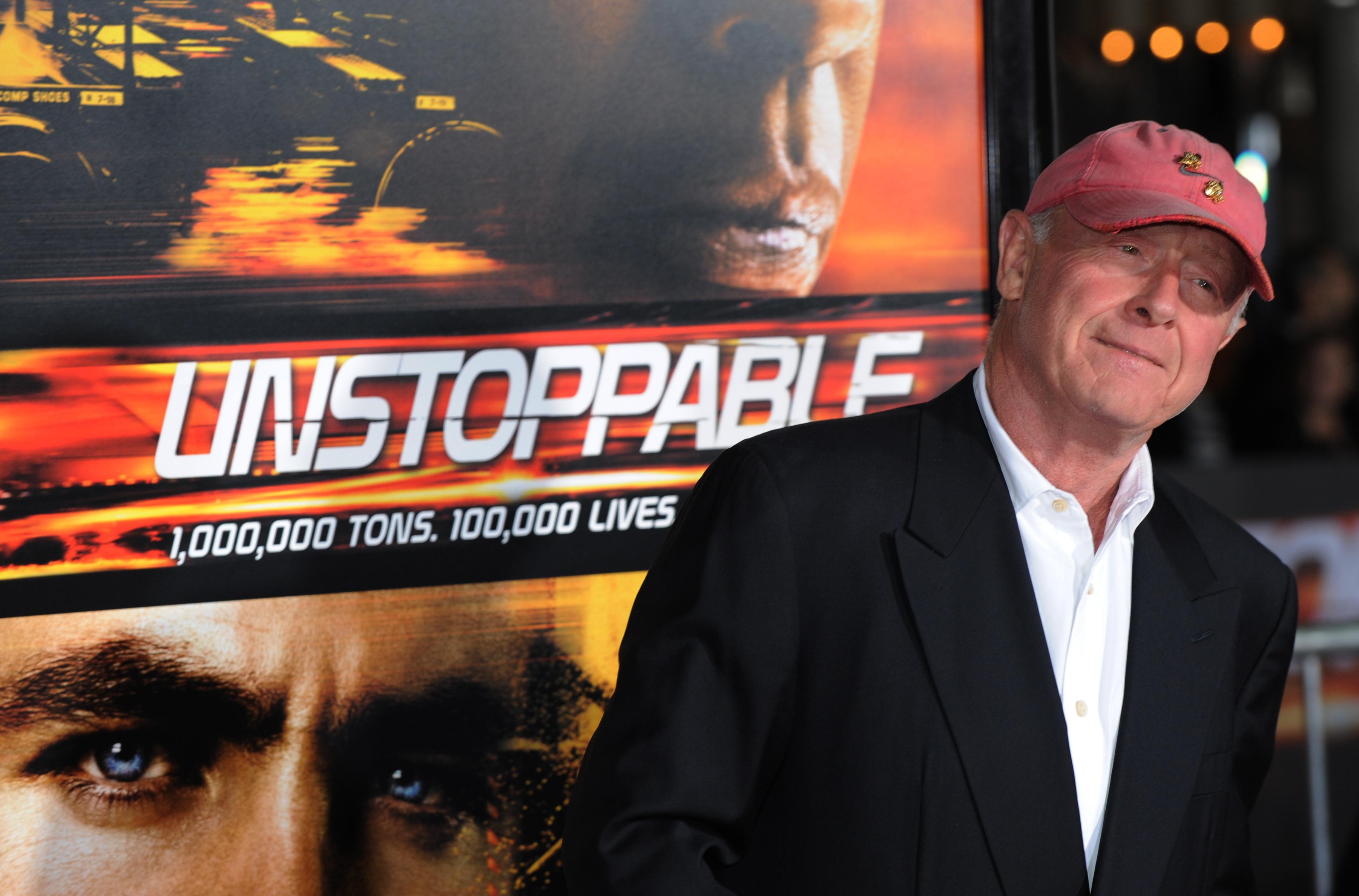

Since those years watching Tony Scott’s movies with my own brothers, I’ve largely lost interest in his work. But he continued to keep up the standard he set with his earlier films. His last release was Unstoppable, another film with a simple, elevator-pitch premise—Speed with a train!—that was executed with impeccable craft and style, receiving real (if modest) praise from audiences and critics. Scott did take on a handful of odder, riskier projects over the years—he gave a young Quentin Tarantino one of his first breaks by directing Tarantino’s screenplay for True Romance—but his legacy is most keenly felt in today’s action thrillers, from directors like Michael Bay, who have pushed his flashy, sometimes disorienting style to its limits (and beyond). I can’t deny the value Scott’s films had to 14-year-old me, even if I’m now troubled by how squarely Hollywood devotes its money on appealing to today’s adolescent males. For better and worse, Scott was among the very best at making sure those teenagers left the theater happy.