Gore Vidal died yesterday after 86 years among us lesser mortals. He spent the last 25 of them less resembling a novelist than a “literary figure”—good for a tart topical quote, great for a withering talk-show quip, excellent at deploying his hauteur on screen in a cameo, unparalleled at being an answer to a Trivial Pursuit question (Genus II Edition). This is not a knock; America needs literary figures (or at least she used to) to talk back to her about her vanities and inanities and grotesqueries, and Vidal’s talk had a rare erudition and a half-of-fame plumminess to it. It’s simple to hotly splutter about the military-industrial complex, but much more difficult to be wry about it. Can we briefly marvel at his sui generis celebrity?

The success of Vidal’s engrossing 1995 memoir Palimpsest, with its portrait of the young man as a prolific bedroom artist and its promiscuous Zelig-ing through the American century, surely helped to give his grey eminence a silver sheen. Yes, he wrote movingly about Jimmie Trimble, his first and perhaps last love, an athlete who died young at Iwo Jima. But more often he wrote glamorously about gallivanting. Vidal’s talents as a name-dropper are untoppable. Today’s New York Times obit mentions that Vidal “never tired” of discussing his family connection to the Jacqueline Bouvier, earning a special citation for polite understatement. And while it is obligatory for obituarists to remember the episode of The Dick Cavett Show where Norman Mailer attacked Vidal for having compared him to Charles Manson, it is important to understand that the episode was really Mailer’s show. Vidal’s most memorable contributions to that evening of television included an anecdote about catching Eleanor Roosevelt arranging flowers in the toilet bowl and the statement, apropos of nothing special, “I had dinner with Philip Roth the other night.”

If you are to consider Vidal as a novelist, you probably want to suppose that his peer group includes Mailer and Roth, but putting it that way seems rather unfair. One hopes that his death occasions a reassessment of Myra Breckinridge—the transcendent comedy with a transgendered heroine—but does anyone still read his other novels? Should they? The books about power and government have a hard clarity and dashing irreverence, and as long as they are in print, a certain kind of iconoclastic history buff will be rhapsodizing about them at length. But one gets the sense that Burr and Lincoln and 1876 mostly exist to fill shelf space in bed-and-breakfasts. Everyone with a serious interest in American literature sooner or later takes a peek at The City and the Pillar—the name-making, career-stalling, coming-of-age coming-out novel from 1948—but never has there been a homosexual writer more unfit for gay iconography. It was Vidal’s gift to be an outsider among outsiders.

Was outsidership essential to his art and his aura? Prophesying the decline of empire from an aristocratic distance, firing shots at establishment intellectual fashions from a magisterial perch, he was an ideal critic, and the pieces collected in United States—including a breakdown of best-seller lists, a takedown of Susan Sontag, and a sparkling tribute to Dawn Powell—belong on every reviewer’s list of texts to gaze into for inspiration. Vidal was at his best as a public intellectual, and you could argue that, as such, his only peers were James Baldwin and (his nemesis) William F. Buckley, other aces at refining round-toned voices to elegant points.

Elsewhere on Brow Beat

Gore Vidal Was a Great Character—But Don’t Forget His Novels

Gore Vidal Was Less a Novelist Than Our Greatest Literary Figure

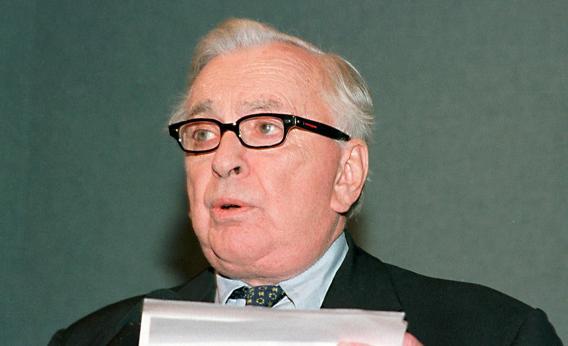

Gore Vidal reads from The Golden Age during a press conference in September 2000.

Photo by MARSHALL H. COHEN/AFP/Getty Images

Advertisement