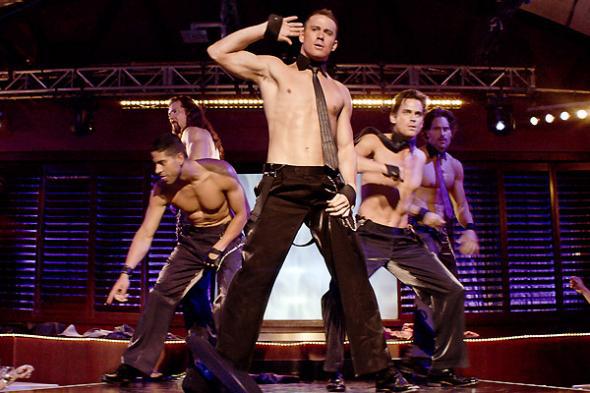

This weekend marks the release of Magic Mike XXL, the sequel to 2012’s Magic Mike. Around the release of the original movie, Slate spoke to various experts in the field of oiled-up abs to research a history of erotic male performance, just as it was finally hitting the mainstream. The article is reprinted below.

When Magic Mike shimmied its way to almost $40 million at the box office this past weekend, it wasn’t the first time that men stripped down on screen. Male strippers have been a recurring plot point in recent decades, tearing off their pants in everything from Summer School to The Full Monty to a wide range of sitcoms and a legendary Saturday Night Live skit. This past May the New York Times even declared that male stripping was finally “hitting the mainstream.”

When did men start stripping professionally?

The mid-to-late 1970s. While musclemen have been paid for popping their pecs and otherwise showing off their bodies since at least the late 19th century, it’s only in the ’70s that stripping became a co-ed profession. And there are only a few known reports of male strippers before the late ’70s. In 1973 Jet told of one such dancer who “peeled down to a black G-string, handcuffed himself to the fence outside” Big Ben and bore a banner labeling him as “The body divine—Angel, the lovely male stripper. Book him.” According to the article, no producers came calling, but the cops did. This was a common problem for the early male stripper. Another early appearance of the term comes in a 1974 report on Deviant Behavior, mentioning male strippers in a report on “Marginally Illegal Occupations and Work Systems.” Through the mid-’70s men who took off their clothes in public were likely to receive a citation for indecency.

However, over the course of the late 1970s male dancers became a regular feature at strip clubs across the country. Some strip clubs reserved a few nights each month for male strip shows, with audiences restricted to “ladies only.” Between 1974 and 1980, the Twin Cities, for example, went from having a few dancers to having four clubs regularly stuffed with screaming women. And male revues—like Los Angeles’ famous Chippendales—weren’t just for the big cities. By 1980 travelling troupes were tearing off their trousers in towns as far as Concord, New Hampshire, where an overflow crowd stunned a local fire prevention officer. “The place was full of women,” he said. “I’m still getting over it.” The Concord performance used a common method for limiting its clientele to women: The cover charge for women was $1, while for men it was $15. By 1980 an Associated Press headline declared, “‘Boylesque’ Replaces Burlesque in Sex Change.” For many the concept was so novel that it required explanation. “They began fully dressed and got down to an orange triangle in front, G-strings and tassels on their rear ends,” one of the New Hampshire patrons helpfully recounted.

Gay strip shows sprouted up around the same time. By 1976 the Gaiety Theatre in Times Square featured men stripping for the entertainment of other men. Unlike the shows oriented toward women, the Gaiety shows regularly featured full frontal nudity on stage. Still, gay shows were otherwise quite similar to their straight counterparts, though there was more likely to be drag and other gender-play.

Straight or gay, many remained unsure what to make of this new phenomenon. The proliferation of male strip shows took place amid larger cultural movements, including the rise of gay pride, feminism’s second wave, and the sexual revolution. (Playgirl was started in 1973 as a feminist response to magazines like Playboy and Penthouse.) But male strippers still faced resistance from many communities. In 1980 six Pensacola, Fla., men and their manager were arrested in Alabama on charges of indecency for stripping. They were eventually found innocent. In another trial the same year, a lawyer argued that male strippers were being discriminated against, given that female strippers danced freely. Men, he said, have as much right as women to strip. At the same trial, the club’s operators were charged with discrimination, for refusing to admit male patrons.

It wasn’t long before movies and TV caught on. The New York Times made its first mention of male strippers in 1979, when an article in the arts section described the TV sitcom The Misadventures of Sheriff Lobo. In the show a corrupt sheriff and his deputies agree to protect a new disco joint, and are “shocked to discover that all of the strippers were male.” Male strippers would become an increasingly popular plot point throughout the 1980s, starting especially with the 1981 NBC TV movie For Ladies Only, and continuing with movies like the 1983 Christopher Atkins romance A Night in Heaven.

Before the 1970s the male body was sometimes eroticized in entertainment, but its sex appeal was rarely an explicit attraction. Even when it was, the attraction almost never involved dancing. In the late 19th century the early vaudevillian strongman Eugen Sandow figured out that if he invited fans backstage, they would throng to see his muscular body in a skimpy costume. Around the same time the American actor Henry E. Dixey appeared in the burlesque musical Adonis, and at the end of the play he would appear topless wearing skintight white bottoms, and showing a bulge. Mr. America pageants became popular around midcentury, and some of these musclemen would dance in chorus lines behind sex symbols like Jayne Mansfield. Still, the male contributions to these performances weren’t explicitly sexual. A handful of scantily clad male go-go dancers would begin dancing on bars and in cages in the 1960s—but they did not strip. Elsewhere, men began appearing as attractions in sex shows—such as Cuba’s “Superman,” who would reportedly reach orgasm without ever touching himself. Gay pornographic films also occasionally appeared in the early 20th century, but it was only in the late 1960s and 1970s that pornographic movie theaters were legally recognized. Before the male body could be seen stripping on stage, it had to be eroticized.

Outside of changing hairstyles and some additions to their playlists, male strip shows haven’t changed much over the last few decades, and today they proceed much as they do in Magic Mike. Unlike at girly bars, male strip shows tend to feature elaborate choreography and a healthy dose of humor. Male strip shows have what they call “playwrights” who script out each beat of the performances, determine the costumes, and choose the participants for each number. They may also have a director who helps realize the playwright’s ideas, and who might double as a dancer in the troupe. To recruit dancers, directors may place want ads, or they may approach prospects they encounter in health clubs, on college campuses, or anywhere else around town, just as in Magic Mike.

So what will $20 get you at a male strip club? A joke in Magic Mike implies that there’s an underbelly to male strip shows, but most dancers reportedly keep their performances chaste. In many cities and states, full frontal nudity is illegal when combined with serving alcohol, and most joints opt to sell drinks rather than let it all hang out. In some clubs a $20 tip might get you a lap dance in a private room, but even then the performance—whether at a club or a bachelorette party—rarely goes further. Similarly, studies have suggested that male dancers are less likely to engage in prostitution—though they’re more likely to date clients. Asked in a sociological survey whether they would recommend their job to a friend, all male strippers who responded, in contrast to their female counterparts, said yes. One male stripper even offered that he “would do it for free!”

Thanks to Joe E. Jeffreys of New York University, Beth Montemurro of Penn State University, and David Chapman, author of American Hunks: The Muscular Male Body in Popular Culture, 1860-1970.

Previously

Mooning: A History