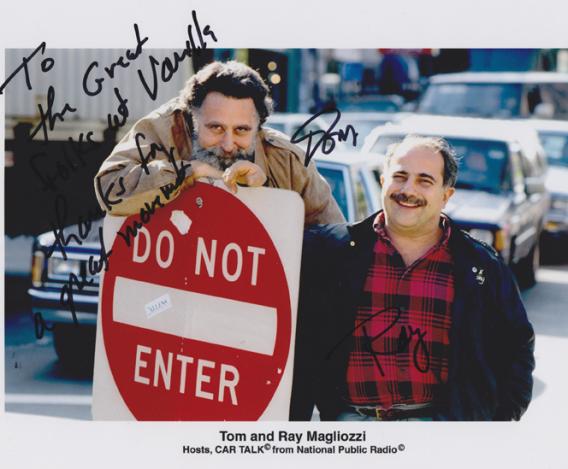

On Monday, Tom Magliozzi, the co-host of NPR’s long-running and beloved call-in show Car Talk, died of complications from Alzheimer’s disease. In June 2012, following the announcement that Car Talk would stop producing new episodes after 25 years, Slate’s Nathan Heller considered the reasons for the automotive radio show’s success. Heller’s essay is reprinted below.

For those of us who spent the boom years mostly in a car, in traffic, going nowhere memorable, news that Tom and Ray Magliozzi would retire from the airwaves comes as less a disappointment than a kind of reckoning. Where did all of that time go, anyway? For 25 years, the Magliozzi brothers, mechanics who speak the mother tongue the way that Lenny Clarke intended, have hosted Car Talk on the tweedy frequencies of the radio dial, offering call-in automotive counsel (long after the golden era of the call-in show) and flights of unadulterated whimsy (long before quirk went mainstream). The show’s disastrous-sounding premise—two guys answer questions about engine lubrication and mufflers at length, on-air, with no editing to speak of—was its secret genius, making every episode a Houdini-style wager to see whether they could squeeze an hour of bravura radio from a few rattling engines. And they always did. Yet what many of us will miss most about Car Talk isn’t the show itself. It’s the contact with a world that the Magliozzis helped invent and bring to life, each week, on the air.

Losing Car Talk feels, to me as to a lot of people, strangely personal. I first started listening as a kid in San Francisco, in my parents’ car, where NPR was ascendant and where Puzzler Tower, winter salt corrosion, Owah Fayah City—all the show’s burnished specifics—seemed a plane ride and a leap of urbaneness away. The Magliozzis call themselves by the Vaudevillian names of Click and Clack and treat the studio microphones the way people treat bowls of beer nuts in a sports bar: as a kind of incidental witness to their private, unhinged, loud, loud, loud enjoyment. Yet their foolery has a kind of vulpine logic, too. Years before Ira Glass sought to break beyond the Cronkite voices of the airwaves, Car Talk did just that, shaping a program that was both guileless-seeming and sophisticated, endearingly blithe and expertly pitched to its audience—an NPR show, in short, that purported not to be an NPR show. Its success is a testament to what the Magliozzis pretend to be, to the invention of Click and Clack, as much as to what they are.

For the odd and slightly uncomfortable thing about Car Talk is that it’s an arrantly white-collar program designed to seem like a blue-collar artifact. The Magliozzis get tremendous mileage out of their Greater Boston drawls (which, somewhat mysteriously, don’t match: Ray, the younger of the two, pronounces most of his Rs; Tom does not) and from the general suggestion that they speak for a profession and cohort most listeners have little experience with: working with a wrench beneath a dripping vehicle. In truth, of course, the two brothers have the pedigree of academics and elite statesmen. As they like to remind audiences from time to time, they both did their undergraduate work at MIT, whose commencement address they’ve delivered; Tom, who holds a doctorate, worked as a college professor for nearly a decade. They write a syndicated newspaper column together, and the interstices of their show are filled with abstruse, university-town wit: the logic “puzzler”; the twee wordplay (Erasmus B. Dragon, Bud Tugly, Heywood Jabuzzoff, Pikup Andropov); the arch, ironic use of car-themed music. Strip away the automotive chassis of the program and it is as mainstream as the Whiffenpoofs.

Yet what saves Car Talk’s backward striving from condescension and minstrelsy is—has always been—the honest yearning that appears to underlie it. The show holds a place in a broader nostalgic tradition, one that praises the local work of hands over the shady reach of corporate industry, the mechanical over the abstract. Craftsmanship is a dying skill, we sometimes hear, and in some sense Car Talk was one of its last public defenders. To host a car show heard largely by people in their cars is to underscore the physical fruit of physical work; to talk about the failures of cheap recent models is to emphasize what’s lost. There’s not a lot of Detroit in Car Talk but enough to make us realize what has gone.

What we’ll miss most in Car Talk, then, is the reminder that good physical work is honorable and matters—even to a Cambridge, Mass., professor. The interaction from the show that I remember best rose when a fussy caller phoned to ask what protective measures he needed to take to avoid being maimed in tire blowouts. The Magliozzis told him he was overreacting—life is dangerous—but, ultimately, their jokes crowded out any advice. “Ahhhhh-ha-ha-ha!” one of them guffawed at the suggestion that the caller attend to his tires in a space suit. “Haaaaah-ha-ha-ha-ha!” the other joined in. In the end, the best thing about Car Talk was the most obvious, too: It’s the only program you can turn to and hear nothing but laughter.