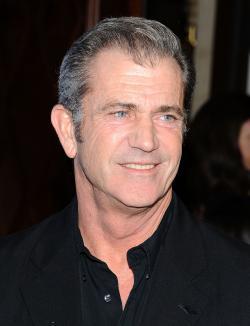

Given the ample evidence—the police reports, the lawsuits, the infamous audio recording of him threatening to put the mother of his one of his children “in a rose garden”—it would be hard to make Mel Gibson seem more deranged than he does already. And that doesn’t seem to be the goal, exactly, of Joe Ezsterhas’ Heaven and Mel, a 30,000 word chronicle of the Basic Instinct screenwriter’s ill-fated attempt to write a “Jewish Braveheart” for Gibson to direct. (The book, originally scheduled for release on Tuesday, was rushed out over the weekend after news of its existence surfaced Friday.)

Heaven and Mel’s most troubling charges are already a matter of public record, detailed in a nine-page letter Ezsterhas wrote to Gibson after the project’s collapse. (Ezsterhas says he knew the letter would become public because “everything in Hollywood leaks to the media,” but he doesn’t take responsibility for the leak. Given that, according to his own account, the only people to receive copies were his lawyer and Gibson’s assistant, it’s hard to imagine the leak coming from another source.) On numerous occasions, Heaven and Mel repeats the letter’s wording almost verbatim, as in its account of the time Gibson, while alone with Ezsterhas’ 15-year-old son, said he’d like to “fuck [his ex-girlfriend] in the ass and stab her to death while I’m doing it.” (Ezsterhas describes this as the “pornographic snuff film” that plays in Gibson’s head.)

But Eszterhas is not entirely content with rehashing his own complaints. He also goes into exhaustive detail about the audio recordings of Gibson raving at former girlfriend Oksana Grigorieva, cataloguing every reference to oral sex as if he were compiling a Biblical concordance. (Gibson, he writes, “had become the greatest American spokesman for the joys and pleasures of fellatio since Bill Clinton.”) The most intriguing new details are mostly minor, like the fact that Gibson sent out emails under the alias “Bjorn Pork.”

Ezsterhas says that the 2006 incident in which a drunken Gibson ranted to a police officer about the “fucking Jews” convinced him that Gibson was an anti-Semite who “shared the mind-set of Adolf Hitler.” But he was convinced that Gibson’s desire to make a movie about the Maccabees, the Jewish rebels who liberated Judea from the Seleucid Empire, was a sincere attempt to atone for his sins. Ezsterhas says that The Passion of the Christ was an integral part of his own conversion to devout Catholicism, which predisposed him to take Gibson’s faith at face value.

Ezsterhas is at pains early on to establish himself as mishpocheh. He cites an award he received for writing about the Holocaust, for instance, as well as his participation in an ADL fundraiser. “I loved Israel and felt a natural and spontaneous kinship with Jewish people and Jewish culture,” he writes. He also describes severing all ties with his father, Istvan, after learning that he wrote anti-Semitic texts for the Hungarian propaganda ministry in the 1930s. Even as he paid for the dying man’s healthcare, Ezsterhas stayed away; his children never met their grandfather.

While Heaven and Mel rarely misses an opportunity to elevate its author at its subject’s expense, here, at least, the parallel with Gibson’s father, Hutton—a conservative Catholic who spurns the reforms of Vatican II and has publicly questioned the scope of the Holocaust—remains mostly implicit. As Gibson grows older, his skin greyed by chain smoking, his resemblance to his father becomes more pronounced, inside and out. He spouts conspiracy theories about a Jewish-Masonic plot to destroy the Catholic Church, opines that anyone ordained after Vatican II isn’t a “real” priest, urges Ezsterhas to forego historical research on the Maccabees and stick to “the Douay-Rheims [Bible] with the Haydock commentary.” “Did you know that Cardinal Ottaviani sat on Pope John Paul I’s face and suffocated him so they could get the Pope they wanted, Pope John Paul II?” the elder Gibson asks Ezsterhas during a visit to a church built with the profits from The Passion.

According to Ezsterhas, Gibson saw the Maccabees as laying the groundwork for the coming of Jesus, stressing the need for a “Christian perspective” on their pre-Christian story. (He says at one point he aimed for the film to “convert the Jews to Christianity.”) “My focus was the Old Testament: The Maccabees,” he writes. “His focus seemed to be the New Testament: Jesus Christ.” Perhaps that’s why Heaven and Mel seems much more interested in smiting the wicked than loving the sinner and hating the sin. For all the time they spent together, Ezsterhas offers little insight into the workings of Gibson’s evidently deranged mind—you’d learn as much from a brief dose of the out-of-control anger displayed on those profoundly unsettling audio recordings. What’s more, the book offers little insight into Ezsterhas himself, apart from an early observation that “my fascination with evil was apparent in my writing.” (Surely you got that Sharon Stone’s character in Basic Instinct was meant to represent Satan, right?)

No one expected Gibson to emerge unscathed from this sordid account. But Ezsterhas ends up with soiled hands as well.