“The hero’s journey” is the backbone of much of our greatest literature and entertainment, from The Odyssey to Star Wars, from The Matrix to Harry Potter. The details change, but the basics remain the same:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder … Fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won … The hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with lots of coins, stars, and—if he’s lucky—cake.

OK, I made up that last part. But fans of the videogame Portal will know what I’m talking about: The hero’s journey is also the basis for many videogames, particularly side-scrollers. And the universality of the story told in these games has perhaps never been illustrated so well as in “Go Right,” a new montage on YouTube that cuts together images from dozens of such games into a story about pressing forward (or in the case of these games, right) no matter how harsh the opposition (enemy soldiers, demons, Goombas).

It’s a brilliant concept, alternately touching and absurd, and sometimes—as when Mario attempts to retreat into his past but finds only an invisible wall behind him—both at once. The execution is also expert. The heroes are filmed in close-up, with just a touch of shaky cam that helps to make even the 8-bit graphics seem cinematic. (The music, taken from the gorgeous score for The Piano, also helps.) The clips come from over 25 years of video games, both iconic (Castlevania, Super Metroid, Sonic the Hedgehog) and forgotten (Gunstar Heroes, The Astyanax, QuackShot). Those nostalgic for those games may be most affected by “Go Right,” but even those who aren’t will grasp the montage’s central theme: When we press forward, we often leave simpler times behind.

Over at the International Business Times, reporter Michael Nunez argues that “‘Go Right’ … Proves Video Games Can Be Art.” But this video doesn’t quite prove that. After all, “Go Right” may have made good art out of video games, but it’s not a video game. Instead, I’d recommend a video game previously noted in Slate that seems to have inspired (or at least anticipated) this video: Passage, a free and simple 5-minute game by indie game-maker Jason Rohrer.

What makes Passage art? Consider this definition from Roger Ebert’s somewhat infamous essay, “Video Games Can Never Be Art”:

I thought about those works of Art that had moved me most deeply. I found most of them had one thing in common: Through them I was able to learn more about the experiences, thoughts and feelings of other people. My empathy was engaged. I could use such lessons to apply to myself and my relationships with others. They could instruct me about life, love, disease and death, principles and morality, humor and tragedy. They might make my life more deep, full and rewarding.

“Go Right” may accomplish this for some viewers; in my experience, most video games, no matter how entertaining, do not. While “Go Right” might prompt you to think about the passage of time, the specter of impending death, and the importance of persisting anyway—I said “might”!—the games it depicts are more likely to provoke reflection about how to get past those dastardly Hammer Brothers without losing too many lives.

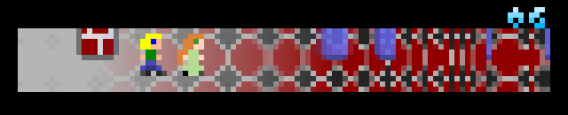

Passage, on the other hand, can definitely make you think about all those things—and entirely through the conventions of a side-scroller. The premise of the game is simple: As in “Go Right,” you move into unknown territory, accumulate treasures and points, and even join up with your own Princess Zelda. While Passage is partly about the conventions of gaming, it also uses those conventions to make a point about life. No matter what you choose to do, no matter how many points you win, every game of Passage ends the same way. You go gray, begin to dodder, and die. It’s a 100 pixel by 16 pixel memento mori, and it only works because it’s something you play, something you control—or at least think you control.

Still from Passage.

Of course, most gamers aren’t looking for great art, they’re looking for solid entertainment. But Passage does point the way to how great art in the form of video games is possible—as long as gamers and game-makers demand it.