In “Freedom of Thought,” the first essay from her new collection, Marilynne Robinson writes that the “locus of the human mystery is perception of this world.” She then expresses her affection for “Calvin’s metaphor—nature is a shining garment in which God is revealed and concealed.”

Robinson has always been utterly unlike most of her literary contemporaries, possessing an uncommon feeling for and belief in the sacred that suffuses her writing. As Tessa Hadley has written, recalling the first appearance of Housekeeping, Robinson’s debut novel about two sisters growing up in a fictional Idaho town: “Her way of seeing things seemed to have sprung from nowhere and was like no one else’s.”

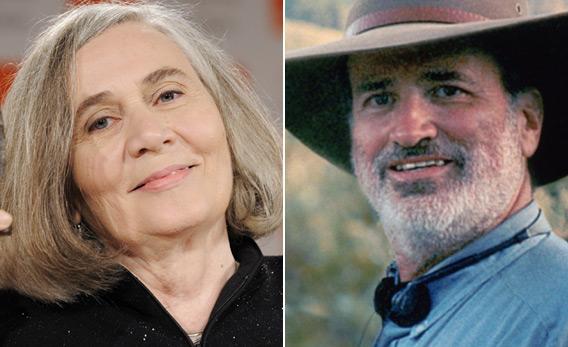

No other writers, perhaps. But reading that new collection, called When I Was a Child I Read Books, confirmed for me a notion that popped into my head sometime after watching The Tree of Life (for which “the locus of the human mystery is perception of this world” would have made an apt, if somewhat pretentious, tagline). If Robinson has a kindred spirit among contemporary American storytellers, it’s not a fellow writer, but a filmmaker: Terrence Malick.

As it happens, the two were born within days of each other, in late November of 1943. Both grew up far away from the big coastal cities: Malick in Waco, Texas, and Bartlesville, Okla.; Robinson in Sandpoint and Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. Those childhoods have provided both artists with abundant material, most notably, for Malick, in The Tree of Life, and, for Robinson, in Housekeeping.

After Robinson published that slim, gorgeous novel, in 1980, she would not publish another for 24 years. That, too, echoes Malick, who took 20 years between Days of Heaven and The Thin Red Line. And lately, each has become almost prolific, Robinson releasing two novels and two essay collections since 2004, Malick making three films since his 1998 return, with a few more apparently soon on the way.

Each has a style characterized perhaps above all by lyrical representations of the natural world. Here is a passage from Housekeeping:

A narrow pond would form in the orchard, water clear as air covering grass and black leaves and fallen branches, all around it black leaves and drenched grass and fallen branches, and on it, slight as an image in an eye, sky, clouds, trees, our hovering faces and our cold hands.

And here is a scene from The New World:

This is not merely a stylistic similarity; it reflects a shared way of seeing the world. Malick and Robinson both seem to espouse, in their work, a deeply philosophical form of Christianity—or perhaps, in Malick’s case, a deeply Christian sort of philosophy—in which the natural world is something like the embodiment of God.

In another essay from the new collection, called “Cosmology,” Robinson writes, “There is dignity in the thought that we are of one substance with being itself, and there is drama in the thought that ultimate things are at stake in these moments of perception and decision.” This line, too, reminded me not only of The Tree of Life but of much of Malick’s work. Robinson then notes that “the cosmos considered in such terms went out of style a few generations ago”—which is true, I think, though at least one of her contemporaries seems to share something of her unfashionable perspective.