Yesterday, Linda Holmes published a piece on the NPR blog Monkey See called “The Incredible Shrinking Liz Lemon: From Woman to Little Girl,” arguing that over the course of six seasons, 30 Rock has transformed Tina Fey’s character from a competent career woman (albeit one with some serious personal failings) into an infantilized woman-child in thrall to Alec Baldwin’s network-running big daddy, Jack Donaghy.

She’s right, though the problem goes beyond the character of Liz Lemon. 30 Rock has gone off the rails, losing track of whatever tenuous hold on reality it might once have had. A new viewer tuning in at the beginning of the show’s sixth season would be hard-pressed to discern exactly what Liz does for a living, let alone the nature of this TGS people sometimes talk about. Even when the show does briefly touch down to earth, crafting a two-episode arc inspired by the controversy over Tracy Morgan’s homophobic stand-up act, it quickly spins off into the ether: In apologizing for Morgan’s character’s words, Liz inadvertently slights the world’s idiots, who turn out to be just as vocal, if substantially less articulate, than the gay community (as Liz duly notes, “the most organized of the communities.”) The strongest scene, in which Fey points out legions of gay co-workers as they pass by Morgan’s dressing-room door, is essentially a paraphrase of the statement Fey released to the media at the time of Morgan’s offense.

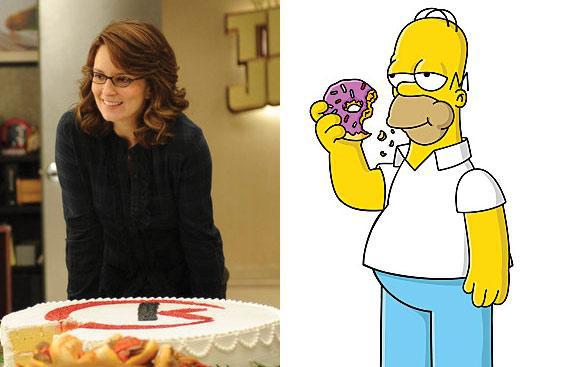

Embracing the vein of surrealism embedded in the modern sitcom isn’t, by itself, a dealbreaker; NewsRadio, for one, only got stronger once it opted to ignore the particular details of its characters’ occupations. But Liz Lemon’s dwindling maturity bears a worrisome similarity to the decline of another once-great sitcom: The Simpsons. For fans who tuned in after the first few seasons, the idea that the show was ever meant to resemble life outside the box may seem straight-up bizarre, but early on—or at least so dedicated fans would argue—it was possible to feel for Homer, Marge, Bart and Lisa, rather than simply laugh at them.

Some put the show’s point of no return at the ninth season episode “The Principal and the Pauper,” where it’s revealed that Springfield Elementary principal Seymour Skinner is, and always has been, an impostor, real name Armin Tamzarian, who pulled a Don Draper-like switcheroo with a presumed-dead comrade from the Vietnam War—the idea being that in the process the show turned up its nose at eight seasons of established continuity. But one of the most persistent early criticisms had to do with the character some fans called “Homer the idiot,” or simply “dumbass Homer.”

Homer Simpson was never the sharpest tool in the shed, obviously. But early on, back when he still sounded like Walter Matthau, he could be seen as an affectionate caricature of a working-class dad: short-tempered and none too bright, but dedicated and loving. That, of course, was before NASA sent Homer into space, before he put on several hundred pounds to claim disability, before he accidentally went to work for a Bond villain (although personally, I’m a big fan of “You Only Move Twice.”)

Liz Lemon hasn’t quite descended to Homerian depths, but she’s getting awfully close. Like Homer, Liz is often funniest when she’s at her most frazzled; last season, she copped to wearing a Duane Reade bag as underwear. But as diminishing returns set in, the bar keeps moving lower, and the hole keeps getting deeper. In the tradition of Fey’s alma mater Saturday Night Live, 30 Rock’s strategy is to work the same jokes harder rather than coming up with new ones—a strategy that’s a lot easier to follow when your characters are made of ink and celluloid. Looking back on Liz’s first season romance with the charming (if absurdly named) Floyd De Barber (Jason Sudekis), it’s startling how far it’s drifted.

To be sure, the only thing differentiating Liz Lemon from any number of socially inept, romantically hopeless sitcom protagonists is that she’s a woman, and you could argue there’s something genuinely transgressive about a TV heroine who keeps her tampons in the fridge and looks like she pulled her outfits from the dirty clothes hamper. (Even so, though, Liz Lemon, you’re no Daisy from Spaced.)

The problem, really, isn’t Liz’s decline per se, but the simultaneous disintegration of everyone and everything around her. The show doesn’t need to be grounded in Liz Lemon’s personal growth, but it needs to be grounded in something.