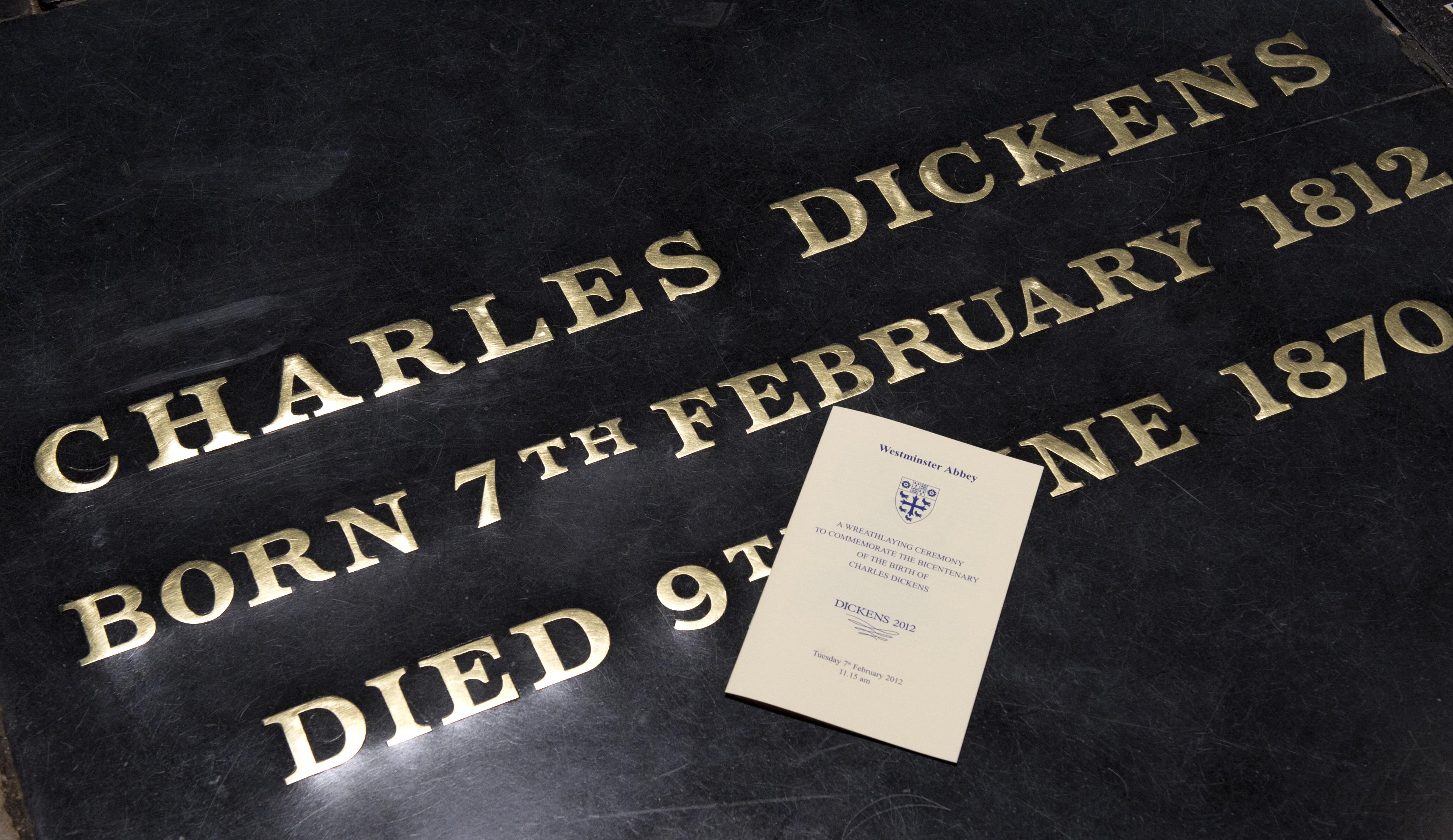

For some in England, this year is all about the London Olympics and the Queen’s Jubilee. For me, though—and, it turns out, quite a few others—it’s all about Charles Dickens, who was born 200 years ago today. I live in New York, but with some persistence and good fortune I found myself this morning an American in London, with a ticket to Westminster Abbey’s “Wreathlaying Ceremony to Commemorate the Bicentenary of the Birth of Charles Dickens.”

In the line outside, blue ticket in hand, I listened to Dickens’s descendants in the queue chat and catch up as if this was an ordinary family reunion. Several jokingly uttered, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” like it was the personal family motto on their coat of arms. One woman, in a pink coat and miniature purple-velvet top-hat fascinator, told her relatives about being interviewed earlier in the morning. She hadn’t had time for breakfast. (Her young cousin handed her a chocolate brioche he had in his pocket.) Dickens had ten children; more than 200 of his relatives reportedly came to today’s service.

I was seated in the sixth row. Our program directed us to stand twice, once for the Lord Mayor of Westminster, and once, when “An organ fanfare is sounded,” for His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales and Her Royal Highness the Duchess of Cornwall. It was difficult to discern organ fanfare from the regular organ music, and we ended up standing for a good five minutes waiting for Prince Charles and Camilla to process.

Photo by Arthur Edwards - WPA Pool/Getty Images

“200 years ago was born one of the greatest writers in the English language,” announced the Very Reverend Dr. John Hall, Dean of Westminster, after welcoming guests. Following Dr. Hall, Dickens’s most recent biographer, Claire Tomalin, read a letter Dickens wrote on March 1, 1844 to his sister Fanny about his celebrity treatment. He’d attended an event where they hung a sign for him that said, “Welcome Dick.” He was, of course, a celebrity in his own lifetime, as he is still, apparently, in ours.

One of Dickens’s descendants, Mark Charles Dickens, has been appointed “Head of the Dickens Family.” He’s also president of the International Dickens Fellowship. He read from a piece his great-great grandfather wrote for those ten children of his, called “The Life of Our Lord.” “Never be proud or unkind, my dears to any poor man, woman, or child,” it reads. “If they are bad, think that they would have been better, if they had had kind friends, and good homes, and had been better taught.” This surprisingly moving piece was followed by our requisite Bible passage, Luke 14: 7-14, in which Jesus says you should serve feasts not to friends or rich neighbors, so they can repay you, but to the “poor, the maimed, the lame, the blind: and thou shalt be blessed; for they cannot recompense thee.”

I’ll admit it. I started to tear up not long after the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Rowan Williams, began speaking. “It is difficult to tell the truth about human beings,” he began. “Every novelist knows this in a special way. And when Dickens sets out to tell the truth about human beings he does it outrageously, by exaggeration, by caricature. The figures we remember most readily from his works are the great grotesques. We think we haven’t met anything like them, and then we think again.” He described Dickens’s honesty about humanity, saying that this is why we have novels and why we read literature.

Photo by Arthur Edwards - WPA Pool/Getty Images

Ralph Fiennes then stepped up to the podium and gave a tearjerking reading from Bleak House. He acted out the death of Jo, the child street-sweeper, with a heart-aching last gasp. My tears were becoming embarrassing. The Dean of Westminster read from the Times report of the burial of Charles Dickens on June 15, 1870: “His genius saw through our trappings, whether of want or wealth, and in life, as in death, his happiness was found in teaching us independence of such externals. He left directions that he should be carried to the grave as an ordinary man…”

The wreath was then set down by Prince Charles. The audience was led in prayer for Dickens and for writers. (And perhaps to make sure the reporters in the room gave the service a good review, we were prayed for, too: “Let us pray for those today who seek to express the truths of creation through the arts; for novelist and playwrights, for actors and directors, for poets and prophets, for commentators and columnists, and for all those who record our own age…”)

We were all then blessed and sang “God Save the Queen.”

Photo by CARL COURT/AFP/Getty Images

I took the tube to Dickens’s house on Doughty Street, where I was presented with a free red velvet cupcake with cream cheese frosting in honor of the occasion. I saw his writing desk and his clerk’s desk, his buffet table, his clock, and a lot of first editions. I saw the special suit that was made for him to wear for his special audience with Queen Victoria. (He had avoided meeting royalty earlier in his life; of course, he had long been treated like royalty himself, even if wasn’t something he wanted.)

The British seem awfully spoiled to me: They have literary greats so esteemed that their Royal Highnesses attend Church to honor them. The Queen will even throw a party. Plus they get to wear fascinators for so many occasions. When Herman Melville turns 200 in 2019 will the American president hold a ceremony in his honor and visit his house the way Prince Charles did this morning? I’m guessing not.

In England, meanwhile, the whole country seems to have gone mad with Dickens. An organizing body, Dickens 2012, is scheduling events all year long. Last week I walked the marshes in Kent that inspired Magwitch’s arrival in Great Expectations, this weekend I’ll go to Portsmouth and see his birthplace. Visiting just one Dickens house, I’ve decided, isn’t enough. (I’m rather fond of writers’ houses.) He founded institutions for the poor, he gave voice to great suffering. More than nearly any other writer of fiction, he changed the world.

Photo by ARTHUR EDWARDS/AFP/Getty Images