Heading into the peak of flu season, I got to thinking about flu songs. These were once a thing. Consider “Influenza,” recorded by Ace Johnson in 1939 for John and Ruby Lomax, the lyrics of which will surely prompt some of us to run out for flu shots:

Influenza is a disease, makes you weak all in your knees

’Tis a fever everybody sure does dread

Puts a pain in every bone, a few days and you are gone

To a place in the ground called the grave

Or, even better, “Jesus Is Coming Soon,” a terrific tune by Blind Willie Johnson:

Why don’t people sing about disease like that anymore?

To answer that question, it’s worth examining, at least briefly, the history of disease songs, which in some form go back at least to the Middle Ages. The big disease back then, of course, was the bubonic plague. Guillaume de Machaut, who survived the scourge of Europe, wrote about it in his Le Jugement du Roi de Navarre, from the 14th century. The speaker of this poem set to music “spends the winter locked in his room for fear of the Plague, meditating on the calamities of the age.” You can hear part of the composition below:

(The same epidemic is often said to have inspired “Ring Around the Rosie,” but historians say this probably isn’t true.)

As with de Machaut’s lyrical take on the Black Death, the best disease songs reflect the zeitgeist. Take, for instance, “Some Little Bug Is Going to Find You,” a ditty about food poisoning that was recorded in 1915—one year before Frigidaire produced the first self-contained refrigerators:

Every microbe and bacillus has a different way to kill us

And in time they all will claim you for their own

For there are germs of every kind in every food that you can find

The heyday of the American disease song begins a few years after that tune; its golden age is in the 1920s and ’30s. A good example from this period is “Meningitis Blues,” in which Memphis Minnie sings, “I would have a foaming at the mouth / the meningitis killing me / I’m spinning I’m spinning baby / my head is nearly down in to my knees.”

Note how specific the lyrics are: That’s typical of the disease songs from this period. While Memphis Minnie lists her symptoms, Jimmie Rodgers addresses, in detail, various treatments—in his case, for tuberculosis. “Don’t worry about consumption,” Rodgers sings, “even if they call it TB”:

“You take all your medicine you want, I’ll take good liquor for mine,” says Rodgers. He died of tuberculosis at 35.

Besides offering—one imagines—some sliver of comfort to sufferers, such songs sometimes conveyed genuinely useful information. In 2003, Dan Baum wrote in The New Yorker of the spate of early-1930s blues songs about “jake leg,” a paralysis caused by drinking a strain of Jamaica ginger extract, a cure-all snake oil often imbibed in place of liquor during Prohibition. The first record of the condition’s connection to the medicine shows up in a song by Ishman Bracey called “Jake Liquor Blues.” Medical records at the time were pretty spotty—especially for the poor people who comprised the majority of those afflicted with jake leg—so much of what’s known about the disease today is culled from those songs.

Songs about sickness are fewer these days, and you rarely get the level of detail that singers once delved into about their symptoms. Today, when a song is about illness, it’s a good bet that the ailment in question is actually a metaphor for something else—unrequited love or society or what have you. Even when a song’s subject is sickness qua sickness, songwriters tend to shy away from the unpleasant details, either out of squeamishness or a sense of obligation to aim for some higher truth.

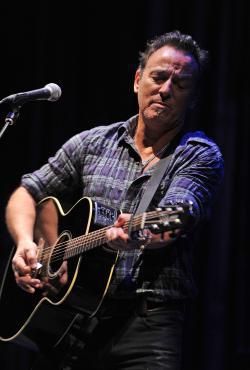

Photo by Mike Coppola/Getty Images

Bruce Springsteen’s “Streets of Philadelphia,” for example, is a great, atmospheric song—but if it wasn’t connected to the Tom Hanks film, you might not know it was about AIDS at all. In “Meningitis Blues,” Memphis Minnie sings about inflammation of the brain and spinal cord membranes and all that comes with it. She goes into detail—and meningitis isn’t a poetic stand-in for anything. When Mudhoney sings “Touch Me, I’m Sick,” we’re no closer by song’s end to knowing just what it is that ails our narrator.

There are exceptions. A recent song by hip-hop artist Lil B, the bluntly titled “I Got AIDS” is something of a throwback to the depression-era sickness songs. It looks at a disease head-on and, like the jake leg songs, offers some cautionary, albeit foul-mouthed, information about the disease—in this case, the importance of getting tested.

For the most part, though, modern medicine seems to have divorced us from our corporeal selves, at least when it comes to music. Because we have doctors to talk to about the grim stuff, we leave it out of the songs. That’s a trade-off I’ll take any time, of course; still, there’s something to be said for the more vivid versions—however grisly—of old.

Previously: