Last week on Brow Beat, I wondered whether long takes—long uninterrupted shots, commonly associated with live-action auteurs, and often several minutes in duration—might actually work best in animated movies. If Tintin’s “long take” was less impressive for being animated—and so prompted fewer viewers to wake from the spell of the movie to wonder, “How did they do that?”—then perhaps the immersive quality of long takes could best be exploited in animation. At the end of the post I asked readers to share any animated long takes they knew of—noting that such scenes seemed to draw less far less attention to themselves than their live-action equivalents.

Our readers once again came through, pointing out a wealth of great animated long takes. It is perhaps unsurprising—and in keeping with the argument of the original post—that most (if not all) of these scenes were pointed out by readers who work in animation themselves. While many commenters pointed to their favorite live-action long takes—the ones you’re more likely to notice, for better or for worse—just a handful of people nominated about a dozen great uninterrupted sequences from throughout the history of animation.

As one of these nominators explained, just because continuous sequences in animation don’t pose all the same challenges as live-action long takes doesn’t mean they don’t bring their own considerable hurdles. Indeed, Martin Scorsese has said that Hugo’s CGI-assisted “long take”—the long descent through the clocktower—was perhaps the most difficult sequence in the film, and had to be “filmed in bits and pieces over the entirety of the 140-day shoot.” In filming Tintin’s continuous sequence, Spielberg was thrilled that “suddenly [his] imagination wasn’t limited by the exigencies of physical outdoor production,” but he said that “it took about a year and a half to get it on film.” Commenter “emuhero,” who says he helped plan some of the long takes for Robert Zemeckis’ motion-capture A Christmas Carol (more on those below), explained why producing these sequences can take such a painstakingly long time:

CG films, as anyone in the industry will tell you, are difficult and expensive to produce, and long takes in CG films are REALLY difficult and expensive to produce. Really long takes simply break the standard methods we use to produce shots in CG studios, and it takes a lot of extra planning, orchestration, computer processing, and data wrangling to pull them off. Computer graphics may make shots like this possible, but it doesn’t make them easy.

With all the work that goes into these sequences, perhaps it’s time that they got their due attention. Here, with the help of our commenters, are five of animation’s greatest “long takes”:

The Polar Express (2004)

In last week’s post we mentioned the computer-generated long take that opens an earlier Zemeckis film, Contact, but his recent motion-capture films also contain some transporting continuous sequences. His most elaborate takes appear in A Christmas Carol. In the opening credits, the viewer is taken on a sort of God’s-eye tour of all of Dickens’ London, the best and the worst, in one smooth shot. The several-minute-long Ghost of Christmas Past sequence, on the other hand, flies across time to Scrooge’s youth, without any apparent cuts.

Two separate commenters suggested that Spielberg’s inspiration for Tintin’s sequence is likely to have been the above scene—also about chasing some precious paper as it flutters through the air—from Polar Express. As emuhero pointed out, the sequence echoes another famous Zemeckis sequence (filmed in live action with the assistance of a blue screen): the opening shot of Forrest Gump.

Cannon Fodder (1995)

An entire short film shot in a distinctive long-take style (and one third of the feature-length suite Memories), Cannon Fodder could be thought of as an animated cousin to Rope or Russian Ark. Just from the short clip above (note that the soundtrack has been swapped out—no other clip was available) you can see how director Katsuhiro Ohtomo (creator and director of the landmark Akira) had to elaborately plan out the movement and placement of each shot in order to tell his story.

Jumping (1984)

Another commenter, Chris Lanier, pointed to Jumping, a six-minute one-take short embedded in its entirety above. Written and directed by Japanese manga master Osamu Tezuka, Jumping puts the viewer in the extraordinary shoes of a child who gradually jumps higher and higher, first over a car and then over a house and then, well, quite a bit higher indeed (I won’t spoil it).

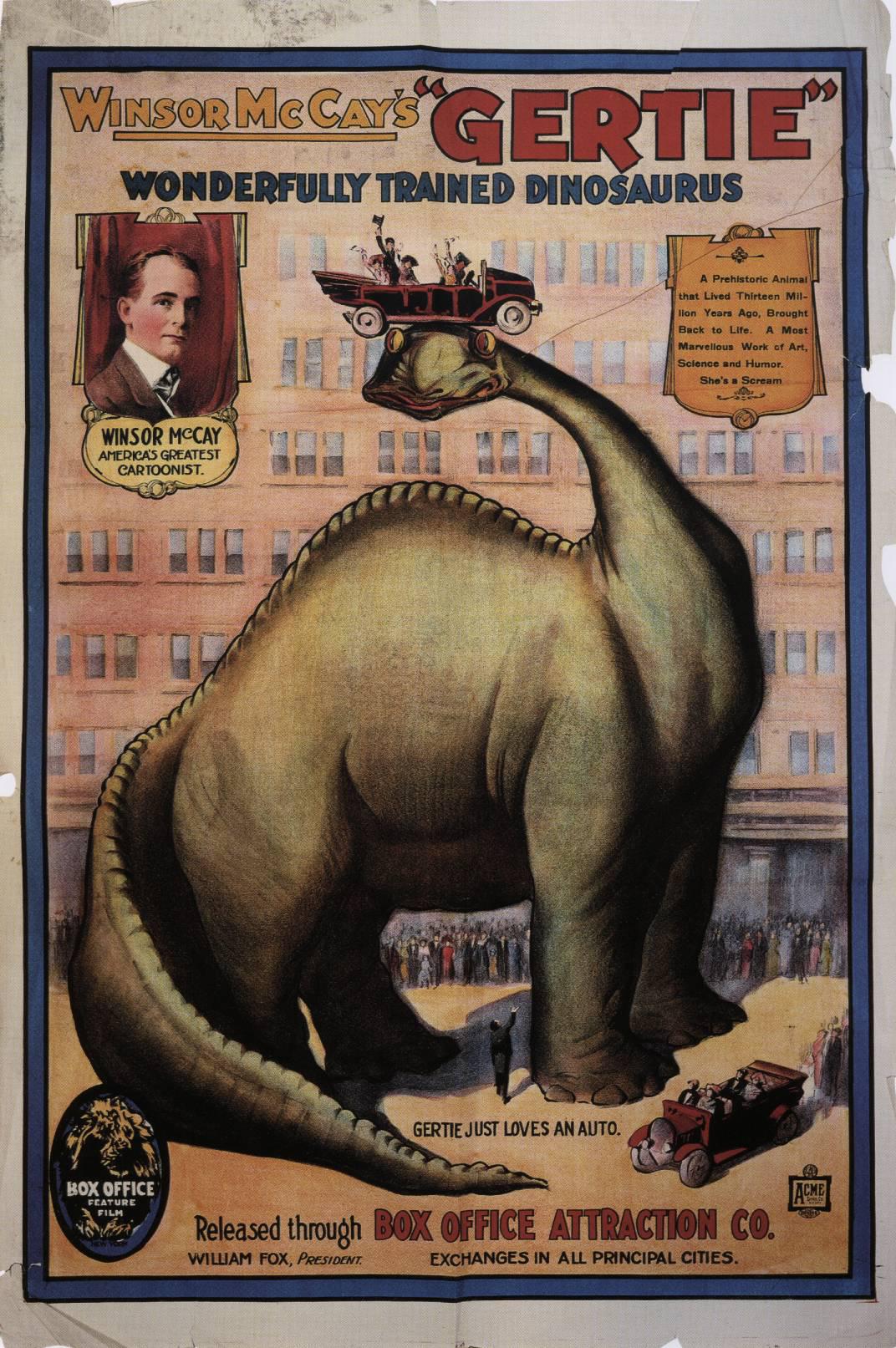

Gertie the Dinosaur (1914)

Commenter Scott explained this one best:

The history of the animated form actually begins with a long take. One of the earliest examples of cinematic animation is Winsor McCay’s 1914 Gertie the Dinosaur which consists, other than an introductory live-action framing device, of a single five minute long take of an animated brontosaurus. Being a silent film, the shot is broken up with intertitles, but the animation itself represents a continuous motion. Like many films that predate the cinematic grammar established in Griffith’s 1915 Birth of a Nation however, the length and framing of the shot seems a nod to the unbroken theatrical proscenium arch rather than directorial hubris. The application of this perspective could later be traced to a forebear of computer animation, Pixar’s 1986 Luxo Jr., itself composed of a rather long take.

I’d submit that its influence might also be traced to Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, in which another live-action character (John Hammond) similarly interacts with a cartoon on a screen (in this case, the dinosaur comes in the form of Mr. DNA).

Fantasia (1940)

Classic Disney, too, has its animated “long takes.” The final shot of Fantasia, which fades in around the 2:20 mark in the clip above, follows a candlelit predawn procession through the woods and into the day to the sound of Ave Maria. As many times as I’ve watched this movie, I’d never thought of this scene as a long take, and now that’s just one more thing I like about it.