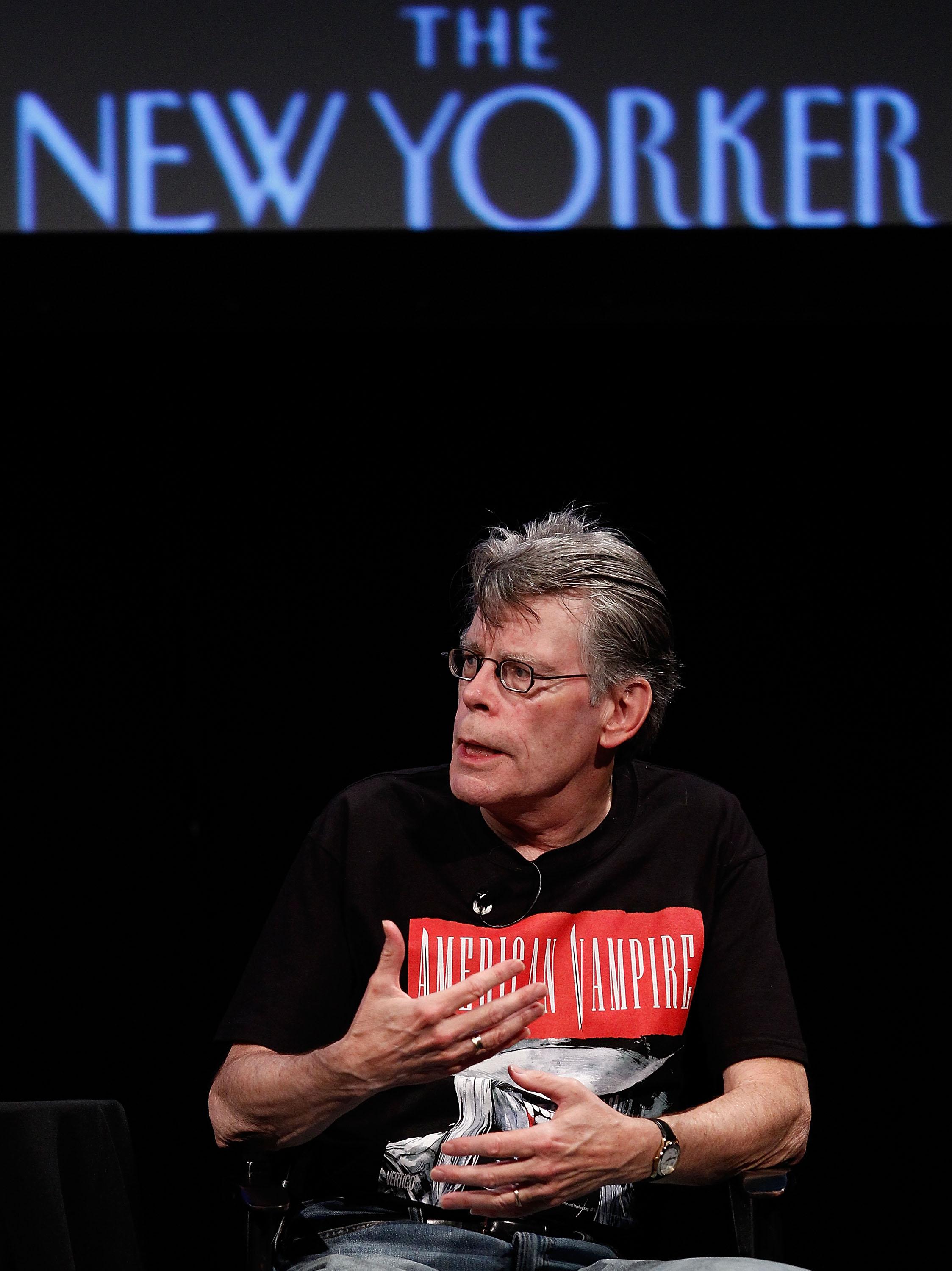

The New York Times’ list of “The 10 Best Books of 2011,” announced today, includes four first-time novelists and one fifty-first-time novelist. The NYT’s own analysis of the list points out that the number of first-time novelists is unprecedented—the only other year more than one first-time novelist made the list was in 2007, when Michael Thomas’s Man Gone Down and Joshua Ferris’s Then We Came to the End were both selected—but it makes no mention of the one 51st-time-novelist (give or take a novella), Stephen King.

The inclusion of a Stephen King novel on the NYT’s list, over entries from lauded literary heavyweights like David Foster Wallace, Jeffrey Eugenides, and Haruki Murakami, is surprising but not unheralded. While this is King’s first appearance on the NYT’s lists, one of the more notable literary developments of recent years has been increased respect for genre fiction, that sphere of publishing in which Stephen King is perhaps our most prominent author. (While his novel on the list, 11/22/63, is not the sort of horror fiction he is best known for, it is a work of alternative history, another often disrespected genre.) In 2004, Time book critic Lev Grossman noted increased interest in genre fiction from literary luminaries like Jonathan Lethem, Margaret Atwood, and Michael Chabon, and suggested that the distinction between popular fiction and literary fiction was breaking down. Chabon himself wrote a sort of book-length manifesto arguing that literary writers could learn from these page-turners, and this year acclaimed writers like Colson Whitehead—who wrote a literary zombie novel that stirred up its own controversy in the Times—continued to mine this borderland.

King has received dozens of awards—including the highest honors from the Horror Writers Association, the World Science Fiction Society, and the Mystery Writers of America—and his books have sold hundreds of millions of copies, but they’ve won less acclaim in literary circles. He did receive an O. Henry Award in 1996, and a lifetime achievement award from the National Book Awards in 2003, but the NYT itself noted that this was only “under pressure from publishers,” and not without controversy:

Told of Mr. King’s selection, some in the literary world responded with laughter and dismay. “He is a man who writes what used to be called penny dreadfuls,” said Harold Bloom, the Yale professor, critic and self-appointed custodian of the literary canon. “That they could believe that there is any literary value there or any aesthetic accomplishment or signs of an inventive human intelligence is simply a testimony to their own idiocy.”

Richard Snyder, the former chief executive of Simon & Schuster, which is now Mr. King’s publisher, and a co-founder of the awards organization, said, “I am startled every time you say it.” He added: “You put him in the company of a lot of great writers, and the one has nothing to do with the other. He sells a lot of books. But is it literature? No.”

Following a year often spent rehashing the relationship between literary and genre fiction, the NYT’s selection of a Stephen King novel could be another small sign of increasing respect for genre.

The NYT’s complete list:

Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding

Stephen King’s 11/22/63

Karen Russell’s Swamplandia!

Eleanor Henderson’s Ten Thousand Saints

Téa Obreht’s The Tiger’s Wife

Christopher Hitchens’ Arguably

Ian Brown’s The Boy in the Moon

Manning Marable’s Malcolm X

Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow

Amanda Foreman’s A World on Fire

Coverage in Slate:

Judith Shulevitz reviews The Art of Fielding.

Daniel Engber reviews Thinking Fast And Slow.

Slate’s Audio Book Club on Swamplandia!.

Natalie Hopkinson on Malcolm X for partner site The Root.

Christopher Hitchens’ Slate column Fighting Words.