Martin Scorsese’s Hugo starts as an adventure film and ends as a historical drama. You wouldn’t know this from the movie’s marketing—the very genre of the movie is a sort of second-act twist. But after opening with the saga of an orphan seeking a missing key so he can unlock the mysteries of a mechancial man, Hugo swerves to become a historical tribute to the transporting power of the movies.

Those moviegoers who haven’t read the book by Brian Selznick on which Hugo is based may be caught off guard by this twist. (I suspect that some of the audience in my theater never entirely figured it out, though they seemed to be plenty captivated anyway.) With that in mind, here’s a quick cheat sheet for sorting out the magic from the realism in Hugo. (Warning: There are mild, historical spoilers ahead.)

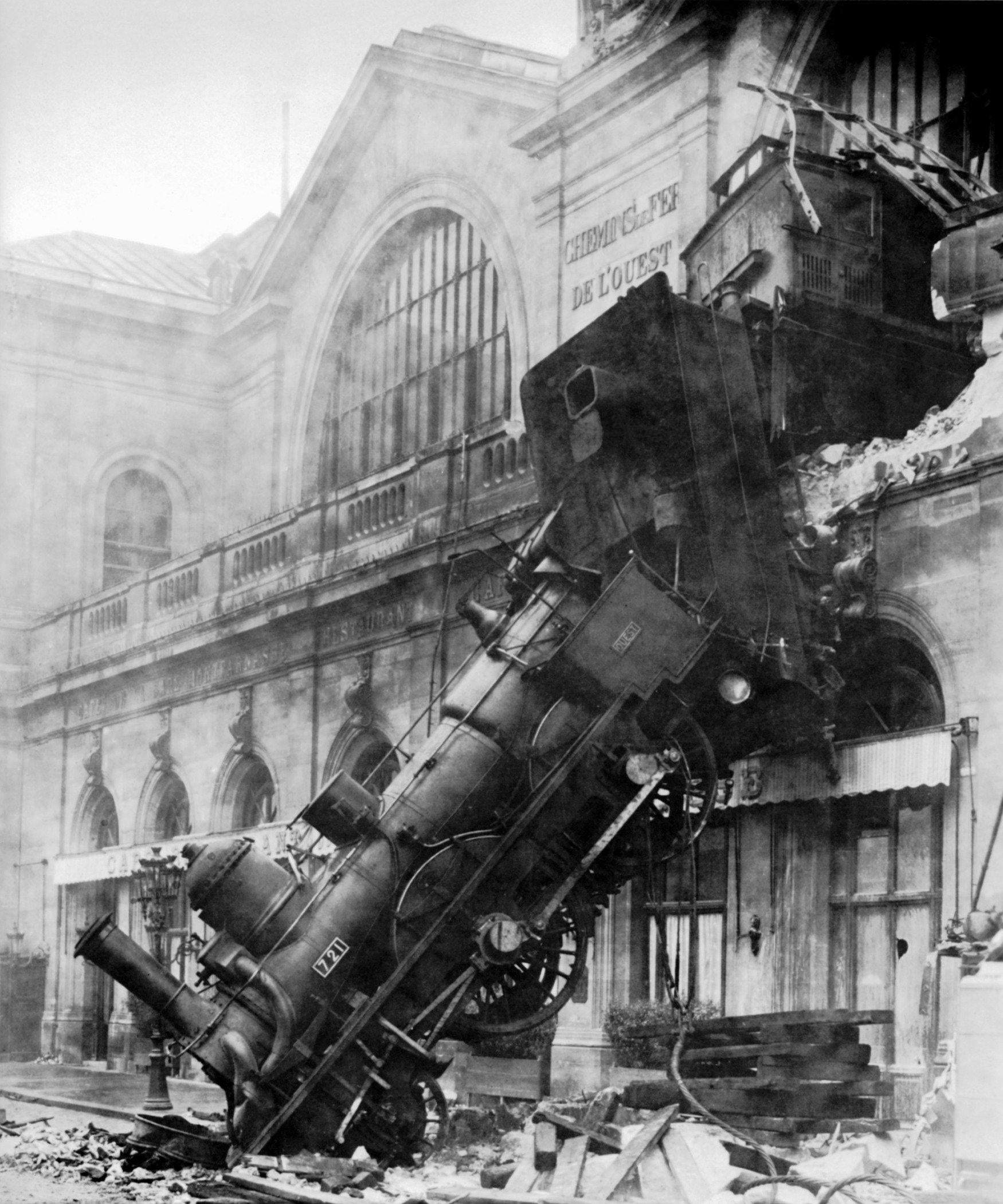

Photograph of the train derailment at Gare Montparnasse from Wikipedia.

Georges Méliès, played by Ben Kingsley in the film, was indeed a turn-of-the-century French filmmaker. He was truly a magician before attending his first movie—a movie that was made by, yes, the Lumière brothers and shown at (yes again) a Paris sideshow. He did fall into obscurity and end up running a toy store at the Montparnasse train station in Paris. (You can see a picture of Méliès in his store, which looks almost exactly as Scorsese presents it in the film, here. Also, a train did crash through the station in 1895, as pictured in the famous photograph on the left; the movie alludes to this event in a dream sequence.)

Most of Méliès’ films as shown in Hugo are also very real, and they were in fact made in Méliès’s greenhouse-like glass studios, just as Hugo depicts. While many of them were lost—during World War I the military commandeered the filmmakers’s office along with about 400 films in order to melt them down to make, yes, boot heels—a large store of them was later discovered in 1929. These discoveries were shown at a gala honoring Méliès that same year, much like in the movie. (Méliès never quite regained his former fame or fortune.) Most of the other movies featured in Hugo, from Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery to the Lumière brothers’ Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat, are shown in their original form as well—though the story of the audience jumping out of the way of the latter’s oncoming train may be apocryphal.

The farther it gets from the story of Méliès and his movies, the more fictional Hugo gets. From what I have been able to gather, there was no Hugo Cabret (Selznick says he named the character after a toy) or René Tabard (the film scholar and preservationist played by A Serious Man’s Michael Stuhlbarg; as The New Yorker’s Richard Brody notes, the latter shares his name with a character in Jean Vigo’s 1933 short film Zero for Conduct—which Selznick cites as an influence). However, there was indeed a Mama Jeanne (the character played by Helen McCrory in the film): Jehanne D’Alcy, Méliès’s longtime mistress and star, whom Méliès eventually married in 1925.

Even Hugo’s automaton has its basis in reality. Automata like the drawing robot in the film were a very real attraction at the time (and as early as the 18th century). Méliès himself bought and tinkered with several such figures, the creations of Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin (the magician from whom Harry Houdini, born Erik Weisz, took his name).

Through the magic of the modern age, we can now watch many of Méliès’ films on YouTube. Below are two of Méliès’s most famous films, each featured in Hugo: Le Voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon), considered the first science-fiction film, and Le voyage à travers l’impossible (An Impossible Voyage). The second is presented with an accompanying narration, which Méliès commonly used at screenings of his films, and also features the hand-painted color and stop-trick techniques that Méliès popularized. Just as it costs extra to see Hugo in cutting-edge 3D, distributors like Méliès charged extra to show the films in color.