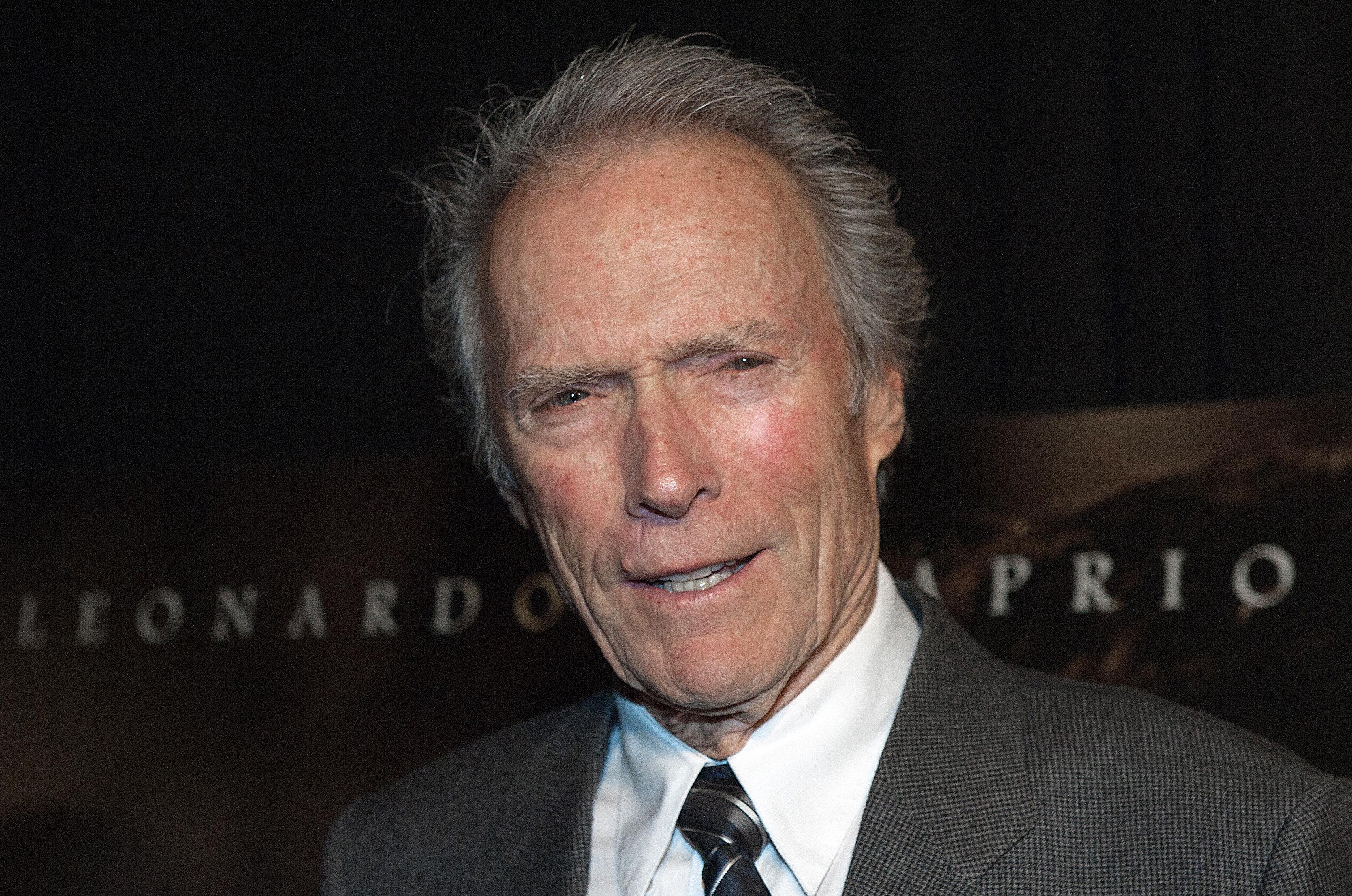

The release of a new Clint Eastwood film—J. Edgar, in “select cities” today, more on Friday—provides an occasion to consider something: Should directors score their own movies? Eastwood has scored all of his since 2003, joining the likes of Mike Figgis, Robert Rodriguez, John Carpenter, and Tom Tykwer—directors who serve as their own in-house composers.

Director-composers are a rare breed, but not a new one. Charlie Chaplin often wrote music for his films (albeit with assistance in orchestration); his music for the 1952 film Limelight earned him an Oscar. For most mere mortals, though, assuming this double-duty seems to be asking for trouble. Isn’t directing a movie hard enough? Why would anyone take on the additional headache with so many good full-time composers available?

Sometimes the reason is simple: money. When John Carpenter directed Halloween in 1978, he didn’t have a budget for a composer. According to Mervyn Cooke’s A History of Film Music, Carpenter originally planned for the film to go without a score. After he screened the movie for a young film executive and found she “wasn’t scared at all,” he wrote and performed his own score on a synthesizer. (He billed himself as the Bowling Green Philharmonic Orchestra, a nod to his hometown.) Thrift, and limited musical chops, paid off with an iconic theme that set a minimalist tone for the next decade of horror movies.

Similarly, Robert Rodriguez used a DIY ethos to launch his career with El Mariachi. He still sometimes works as a “one-man film crew,” responsible for everything from camera work to special effects to sound editing—and also scoring his films. The results themselves are a mixed bag, but they hit more often than they miss.

For other directors, however, the essential issue is not money, but control. Kathryn Kalinak, author of Settling the Score: Music and the Classical Hollywood Film, cites the case of Indian director Satyajit Ray. Weary of fighting with his composers, Ray took up scoring duties himself. The music he wrote, Kalinak told me, works fine. “But then you listen to the Ravi Shankar scores, with whom he fought all the time,” she says. “The Ravi Shankar scores are incredible.”

Kalinak has the same problem with Eastwood’s scores. She describes them also as “fine.” But considering the composers he’s worked with in the past, fine falls short. Eastwood benefited from top-notch scores for much of his career. The great Ennio Morricone scored the Sergio Leone Westerns that made Eastwood a star. Lalo Schifrin (composer of the Mission Impossible theme) did the music for all the Dirty Harry movies. After that, Eastwood enjoyed a consistent and fruitful collaboration with Lennie Niehaus.

So what of Eastwood’s decision to write his own music? He didn’t score a movie by himself until Mystic River, when he was hardly in need of resources. And I don’t think it’s a matter of whether Eastwood thought he could do better than established film composers. Rather, it seems like the next step in an increasingly personal filmmaking career—and a logical one, considering his well-known love of music. Eastwood’s scores dwell nicely in the background—which is especially welcome given that his movies often could use a little restraint.

However, among the six film-music historians and critics I spoke with—most of them fans of Eastwood in general—enthusiasm for his scoring was scarce. Too simple, too repetitive were the main complaints.

Eastwood the composer did have one defender. James Buhler, co-editor of Music and Cinema, said the music by itself might come off as thin, but Eastwood’s knack as a filmmaker ensures that the score serves the story. And he brings an amateur’s passion that pays off in unexpected ways. Buhler points to the score for Flags of Our Fathers, in which the music at times seems to struggle to express the story’s emotions, mirroring the characters’ inarticulateness.

“Because a professional composer’s training equips him or her with a fairly wide range of expressive registers and musical forms,” Buhler writes in an email, “it would have been harder for a professional to capture and convey the same sense of struggle and awkwardness in such a simple piece.”

Thanks also to David Neumeyer, Roger Hickman, and Roger Hall.

See also: David Lynch’s Greatest Music Moments.