What if to save something spectacular you had to risk both its total demise and your own life?

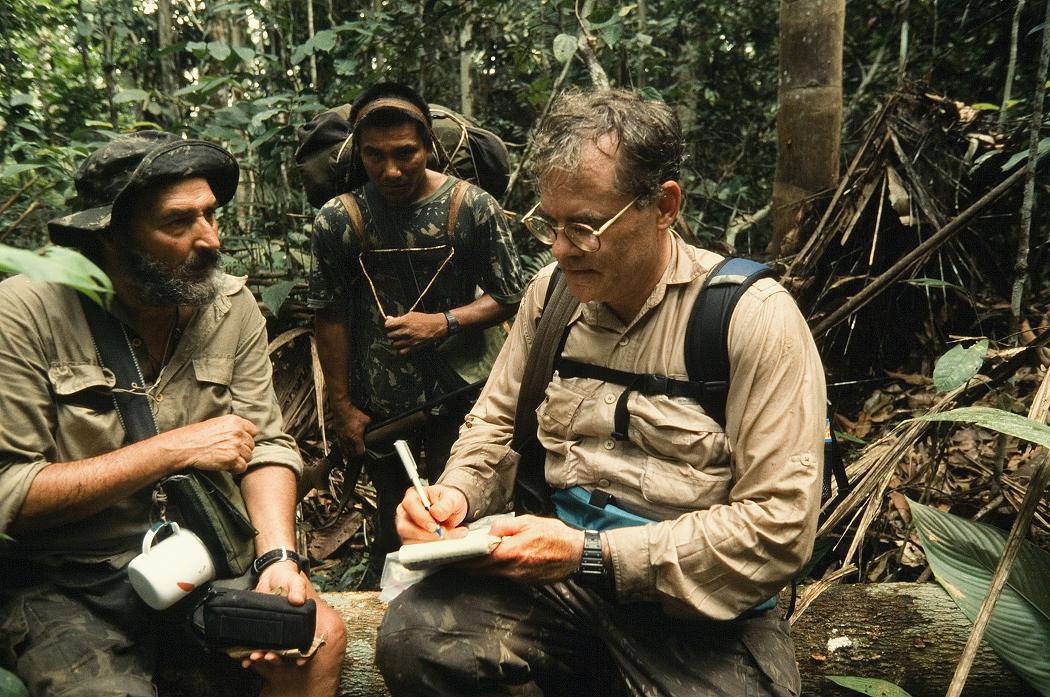

That was journalist Scott Wallace’s predicament when he traveled to Brazil in 2002 to chronicle an unprecedented expedition deep into the Amazon rainforest. In his new book, The Unconquered, Wallace recounts the treacherous quest of a 34-member team of frontiersmen and activists hoping to protect Brazil’s indigenous Flecheiros, or “arrow people”—and the valuable, resource-rich land they inhabit—from commercial interests. To protect the arrow people, the well-meaning outsiders had a daunting task: They had to get close enough to evaluate the tribe’s safety without actually making physical contact, which could have spread devastating disease to the natives.

Wallace described his harrowing experience to a packed crowd at the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C., last Thursday.

“It’s unbelievable. They live completely independent of the world’s moneyed economy,” Wallace said, as pictures of his group hiking through the seemingly impenetrable forests and dining on monkey—the only food available for days—played on a screen behind him. “They’re the last vestige of a society that is changing, and in my mind not for the better.”

The arrow people are among an estimated 5,000-10,000 remaining uncontacted indigenous people who inhabit the Javari lands on the western edge of Brazil, where the Amazon rainforest meets the Andes Mountain range. The tribe’s ethnic roots, language, and cultural customs remain largely unknown to the outside world. What they are known for is vigorously defending their territory from intruders with a distinctive weapon: deadly, poison-tipped arrows.

“Up until this point, it had been a relationship with bullets flying in one direction and arrows flying in the other,” Wallace said, explaining the absence of cultural understanding between the indigenous tribe and the modern world. “But in this case, the benefits outweighed the potential damage.”

Brazilian explorer and Indian rights activist Sydney Possuelo took the lead on the carefully-plotted expedition. On previous occasions, Possuelo saw firsthand how contact with the outside world impacted local tribes—like when he tried to help the Brazilian government safely remove native tribes before the Amazon highway began construction. Those attempts, Wallace said, always resulted in disease epidemics, with up to 90 percent mortality among the native groups. And so Brazil instituted a policy of no contact.

“These people have no immunity to the germs we carry,” Wallace said. To minimize the potential both for exposure to disease and violent conflict, the group planned to stay at least 6 km away from the arrow people’s known dwellings, which Possuelo mapped on a helicopter fly-over before the trip.

But it soon became clear those careful plans could only accomplish so much.

One day, a scout on the expedition found a fresh human footprint. The chilling discovery was followed by the sound of unfamiliar voices nearby. The group carried shotguns for hunting and for any necessary warning shots, but returning fire in an altercation was not an option. Possuelo soon found a universal Amazonian warning: a freshly-snapped tree sapling. He rerouted the group.

“Now we know that they know we’re in their land,” Wallace said. For the remaining weeks of the trip, he and his group had the unnerving experience of constant surveillance by the skeptical natives.

After three months of sleeping in hammocks, enduring 90 percent humidity, and fearing sudden attack by the suspicious arrow people, the group was picked up by motorboat. After drinking the Coke he had craved more than anything (and which was, he said, not that satisfying), Wallace found himself feeling conflicted.

“It may well be the last time ever outsiders enter this land—a one-time thing,” he said.

But by documenting vestiges of tribal society—including thatched huts and ornate totems—the group was able to verify where the tribe was located and that they are indeed using the coveted lands. “They appeared to be safe,” Wallace said. Though pressure from companies eager to enter the Amazon remains, aerial surveillance since the expedition suggests that the arrow people are still thriving—all the while oblivious to the competing interests tugging at their way of life from the outside world.