Tom Waits’ new record, Bad As Me, is his first album of brand new songs since 2004—though Waits will stop you right there and say that Orphans, a three-disc set of rarities from 2006, featured “a hell of a lot of what we call reconditioned songs,” new recordings of old standbys. “Who’s to say that when a song has been used it’s not any good anymore? Everybody’s all hung up on new, you know?”

People aren’t just hung up on Bad As Me because it’s new. For the first time since Mule Variations, Waits has put out a record with the full range of his go-to song-forms. Real Gone (2004) went all-in on drum n’ dirge; the song-cycles Alice and Blood Money (both 2002) took their cues from stage works presented with director Robert Wilson. Bad As Me has the variety of instruments and composition styles of Rain Dogs and other Waits classics.

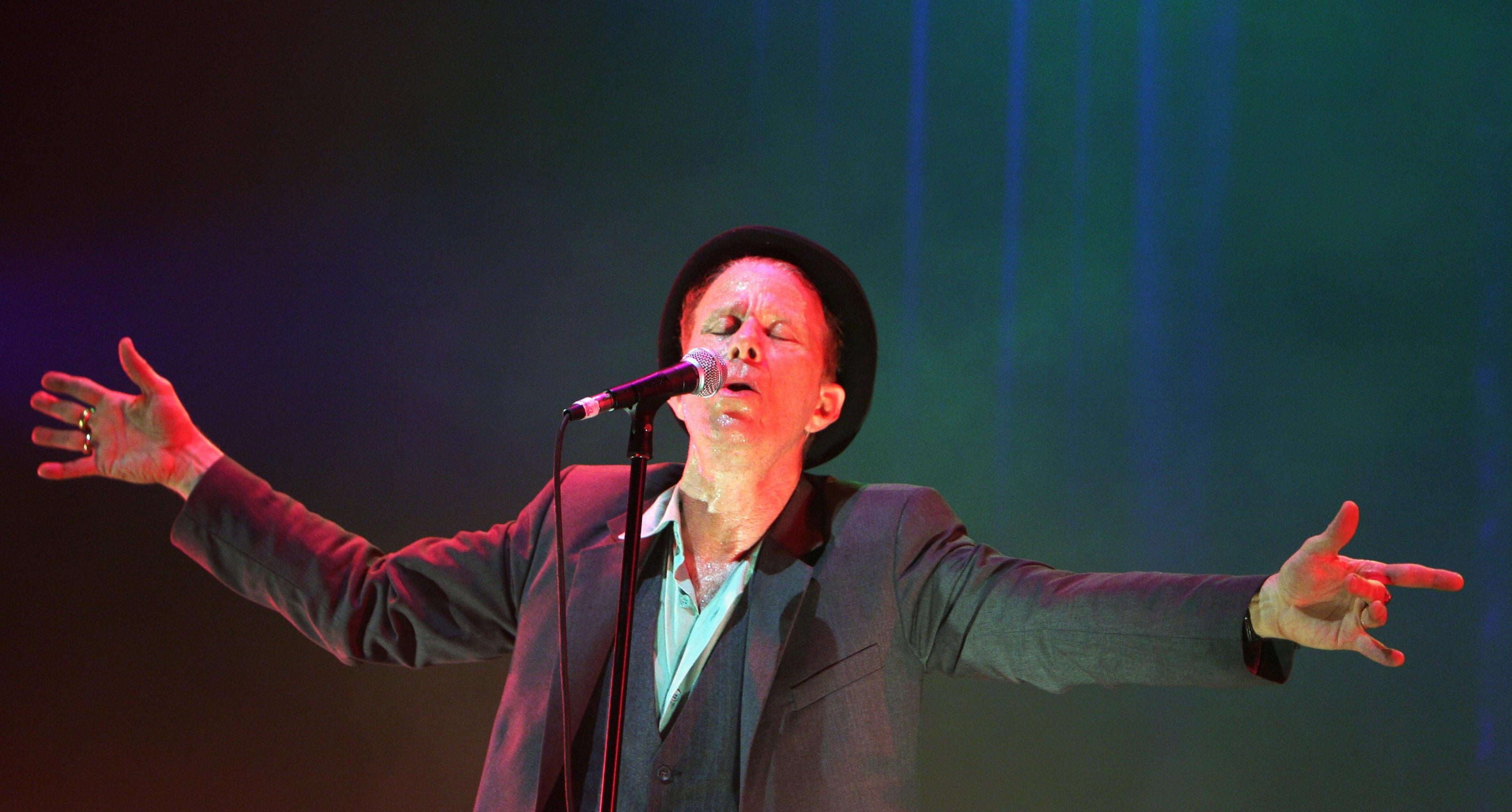

I spoke with Waits about the new album earlier this month. Generally loath to speak in great detail about specific artistic choices, he says things like, “I’m not really conscious of those things,” or, “I’m not any different than anybody else.” Neither assertion may be true, but it’s best to let the man talk: He spins yarns mid-interview as impressively as he does on his records.

Slate: Where are you now?

Tom Waits: In a barbershop. In a little town called … Rio something…. I love to be in a barbershop where I know I don’t have to get a haircut. Just ’cause I hated them when I was a kid. Because you had to go to the barber, it just felt like you were going to have something removed—felt more like you were going to a doctor and they were going to cut off your little finger or something. So now, I’m a grownup, I can go to a barbershop just sit there and read a magazine by the fan, look out the window.

Slate: What else do you remember as vividly from childhood?

Waits: Oh man—my favorite picture of my grandma, she’s in a housedress on a front porch, with a handgun. Probably in the late ’20s. … In Texas, Sulphur Springs. They couldn’t get the gun away from her. You know, they were interested in sewing. She wasn’t interested in [that] … she didn’t even cook. The gun: That was it. Did as many things as she could with it. But, you know: It limited her. [Laughs.] I’m glad I have a picture.

Slate: What kind of gun?

Waits: I have the gun! Oh, in my fireplace, I guess it’s some kind of Colt .45. … I don’t really know guns. And you wouldn’t believe the things she had in her purse. I can’t even tell you. It scared me as a child.

Slate: How much of that history factors into your songwriting?

Waits: Well, I don’t know. It’s not a conscious thing, you know? People say all kinds of things about the ingredients of songs. But you know they are a kind of magic, in the sense that they may easily include a stain on your bedroom wall … and a variety of mis-recollections. And then you name it after a girl’s name that you just made up.

Slate: All the songs on the new record were written with your partner, Kathleen Brennan, right?

Waits: Oh yeah. We worked on all these together. She comes from a completely different discipline. If two people know all the same things, one of you is unnecessary. She’s been listening to a lot of Peggy Lee—and a lot of Henry Mancini and Harry Belafonte. You know?

Slate: What’s been on your playlist?

Waits: Oh uh, you know—Bill Brassiere and the Sleepwalking Assassins. Beaumont Zipperhorn and the Canadian Ankle-fan. … Ginger-Poodle and the Shoehorn Orchestra.

Slate: So the canon, then.

Waits: I.B. Trickle-Shirt and the Belvedere Shine-Holes. My favorite is that new gal. Wears all black, sings real dreary songs: Matinee. Well, she won’t play a matinee! She’s really beautiful, I think her name is Matinee and you can’t get a … [pauses] She has a shaved head and a tattoo of a globe. She stands on a platform that slowly turns and there’s a spotlight on her skull. She sings into a lavalier. And—can’t sing a note! But she’s fascinating to watch. Where were we? Remember, the truth is overrated.

Slate: We were definitely talking about the new record. One thing that struck me was that some of the characters haunting the margins this time around seem less romanticized than their predecessors on prior records. As though they’re drifting or homeless as a consequence of larger forces, and less as a matter of choice? Is that wrong?

Waits: No—no, that’s a good one! I’m not really conscious of those things, you know, when I’m putting it all together. Like, let’s make sure it feels like that. [You’re] trying not to write the same song you wrote before. … I’m not any different than anybody else. You’re trying to challenge yourself—and sometimes you’re a lot easier to please than your audience. And sometimes it’s the other way around.

Slate: You play live pretty infrequently—and, therefore, one would think, to reliably ecstatic crowds. When did you ever encounter a hostile audience?

Waits: Well, they weren’t my audience. [I was] opening for Zappa! They thought that Frank just wanted them to kill me. That must be why I’m there, because I’m not Frank. Anyway—he was using me as a rectal thermometer. He’d ask me later: “How was the crowd?” and I’d realize what my job was. I felt like the geek, you know, biting the heads off the chickens. This was in the early ’70s.

Slate: They would have loved you 10 years later.

Waits: Yeah, I kept telling ’em that! You’re gonna love me in 30 years, fuckers! You’re gonna line up, and you’re gonna beg forgiveness. Uh, but I haven’t been able to reach any of them!

Slate: Those are the fans you should reach out to with your next YouTube listening party. “If you heckled me when I was opening for Zappa in the ’70s, get in touch via such-and-such a manner.”

Waits [Big, grumbly, Tom Waits laugh:] Ha ha ha! … Concert for an audience of one. [Like] they mean that much to me. And then I bring the syringe. Goes right in the neck.

Slate: Or just bring along the old rectal thermometer.

Waits: That would be too poetic.

Slate: The spelling of the new song, “Hell Broke Luce,” where’d that come from?

Waits: There was a prisoner in Alcatraz during a prison riot—this goes back to the ’40s. And during the riot, of course, everyone was nervous, and he scratched on the wall with a knife. And he wrote “hell broke luce,” and that’s how he spelled it. Alcatraz—they have an amazing bookstore. But I got separated from everyone else on the tour. After a while something happened with my headset, and I was out of step and I didn’t know where the rest of the people were, so I just sat in one of the cells for a while.

Slate: It seems like a more pointed war song than you’ve recorded previously.

Waits: Loaded. Anyway. … I’ve been hearing that line a whole lot: “You had a good home but you left.” And so I somehow … ahhh. Keith [Richards] said that officers will hate that song, but enlisted men will love it. The army’s interested in it, as an ad for, you know, their commercials. It’s an answer to “Be all you can be.” I’m having a conversation with them about it. It’s a cautionary tale. Obviously.

Slate: Ha! Well, how was working with Keith Richards again. It had been a while, right? The last album was…

Waits: Bone Machine. Yeah, man.

Slate: I read somewhere that during the sessions for Rain Dogs you had to show him how to move when playing a particular song. Does he still need any coaching from you?

Waits: Oh man, he doesn’t require anything at all. … I didn’t really show him how to move—you can’t show him how to move. I’ve read these … that I was talking in pantomime and body language. I may have been, but I don’t remember. I was probably nervous talking to him and resorting to, you know, hand signals.

Slate: So how was it this time around?

Waits: [The] first time he brought about 200 guitars with him, you know. I said, “Oh man, this is crazy,” you know? He had a guitar valet … he brought a butler and 200 guitars and he pulled up in a moving van. Jesus! This was a little more streamlined though.

Slate: Having Richards and Marc Ribot playing at the same time is the definition of luxury casting, I think.

Waits: Luxury casting! I like that. When you can afford to hire everything! “I want 300 emus on my lawn by 6 o’clock. And I won’t take no for an answer! And I want an 8-foot fence. You know?” And I want—yeah it can get a little absurd like that if you’re out of control on the budget. I have people watching me all the time. … Oh, that gun—my grandma’s. “.44 Smokeless Dance,” that’s the name of it. I just saw it on the barrel … I didn’t realize what it was [before].

Slate: That’s pretty beautiful.

Waits: Say, what was the weather like there?

Slate: It was pouring right before your call, but now it’s just humid and overcast.

Waits: Hey, that’s good! I worked on that while we were talking. Still got the touch.

Interview has been condensed and edited.